Yang Li and Architect Olaf Kneer Have Created a Mobile Music Event Device

- TextHynam Kendall

Speaking to Hynam Kendall, Li and Kneer discuss the ‘HUMAN MAS/CHINE’, which allows artists to perform live in unexpected locations

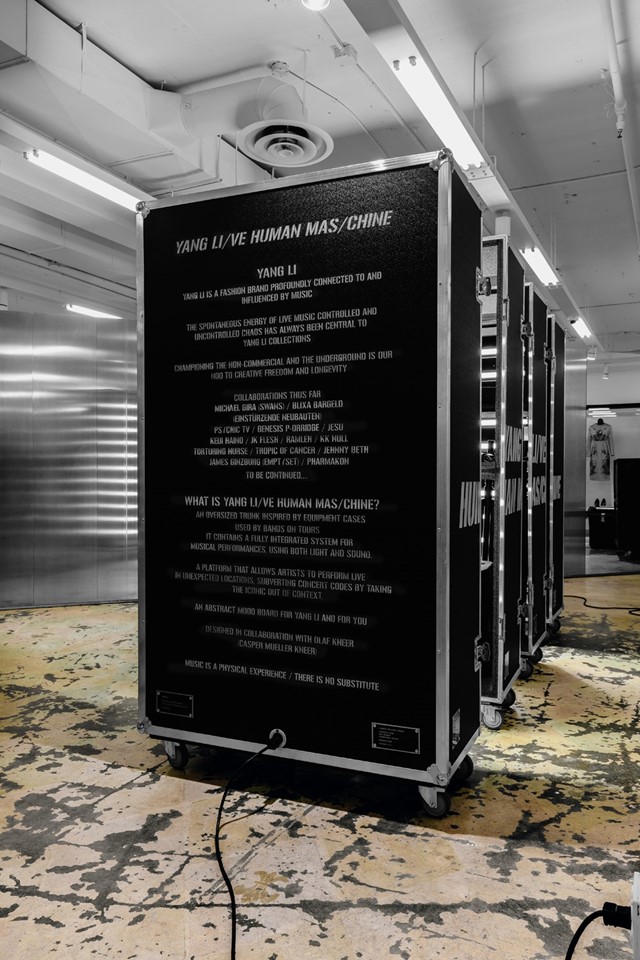

“Yang Li is a fashion brand profoundly connected to and influenced by music.” This line reads in white across the face of a black leather trunk, intimidating in its size, and seemingly traditional in its design. The statement that you read is undeniably true. Li has constantly interwoven music and performance into the narrative of his namesake fashion label, lest we forget the incredible two-day noise festival in London’s Selfridges, his much-lauded merch line for a fictional band, Samizdat, and last season’s amazing performance by Justin Broadrick (of Napalm Death, Godflesh and Jesu fame) in the Gothic church of Saint-Merri where the designer’s A/W18 show was held.

The adorned trunk in question resides in the sprawling 20,000 square foot fashion and retail space ‘Leisure Center’ in Vancouver, and splits to four segments of technical apparatus making it sit somewhere between a music box and contemporary art piece. Inspired by equipment cases used by bands on tour, it works as a kind of “stage area” as well as PA-system, and was christened with a performance by Noise artist Pharmakon (Miranda Chardiet) whose loud, Dadaist act introduced Li’s HUMAN MAS/CHINE project to the world.

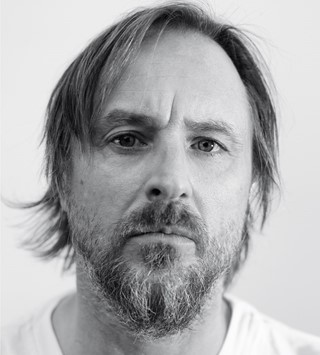

HUMAN MAS/CHINE, masterminded by both Li, and architect Olaf Kneer, of Casper Mueller Kneer, whose CV includes spaces for Céline and White Cube, will be a series of events “allowing artists to perform live in unexpected locations” using a version of the trunk as a base.

Here, Li and Kneer discuss this ambitious series with Another Man.

AM: Leisure Center’s Mason Wu and the store’s Creative Director John Skelton approached you to collaborate with them and HUMAN MAS/CHINE was the outcome. Was the collaboration the genesis for HUMAN MAS/CHINE, or was this something that you were already working on?

YL: HUMAN MAS/CHINE has been an idea that has been growing since [Olaf and I] first met four years ago. ‘Music in fashion’ often manifests as brands just thinking, ‘We’ll have an afterparty and book a band we like to play.’ But it should be more than that. [Olaf] and I had talked about this a lot over the years and wanted to create a ‘gesture’ that was honest about music

AM: You’re very open about your fashion brand having a collaborative relationship with musicians. The HUMAN MAS/CHINE project is separate to the fashion line, was it always set to be standalone?

OK: We quite liked it not being about commerciality. The performances are statements of passion, not a sales exercise. There’s so much selling in everything now. Everyone competing for expendable income. It can kill the message and intention if everything is branded, especially if that’s the main intention. This kind of authentic experience is rarer and rarer.

“We quite liked it not being about commerciality. The performances are statements of passion, not a sales exercise” – Olaf Kneer

YL: It’s true, there’s no clothing so to speak. HUMAN MAS/CHINE’s purpose wasn’t to create the opportunity to dress musical acts. [The acts] should be presented how I’ve seen them. If down the line the clothes work, they work. But the project’s purpose is not to sell fashion. It’s a series of events and will be like a moodboard of my mind – folding out physically in front of an audience

AM: Was it always going to be a series?

YL: Definitely. The opportunity to collaborate [with Leisure Center] was the perfect way to learn the prototype. One could say it’s the beta version. It was also a way to experience how the crowd would work together because this isn’t just the crowd we see at the fashion show. These are secular music fans too. The music that I am into, that we will use in the series, is very different to what my fashion followers might be used to.

AM: Judging from the first HUMAN MAS/CHINE, you want to have a very physical type of performance?

OK: Because we are drawn to risk, I’d say. There’s a tendency to make more risk-free experiences now, so risk-taking is what’s interesting. We would rather enter into this not knowing if it would work out than do something safe

YL: Right, the performers we’re working with are part of the last really authentic music scenes: noise, industrial. Margaret [Chardiet] was physically walking around and interacting in the performance space, not in a violent way, in fact almost in a too-intimate way. Physical contact alone, even without violence to it, is scary. Someone coming up to you and running their face all over your body is a provocation. Someone else’s skin coming into contact with your skin, uninvited, is a provocation. Everything about the series is a provocation. Even down to selecting spaces that are unexpected or contradictory [for a series like this].

OK: It’s quite disruptive, we take a space and re-contextualise it. Like in Vancouver we invited these punks into a commercial fashion space. But we won’t limit [the project] to retail or fashion spaces.

“The performers we’re working with are part of the last really authentic music scenes: noise, industrial” – Yang Li

AM: With the design of the trunk itself, were there discussions about how literal to go with it? Because the artpiece used for the performance in Vancouver was quite literal in its design

OK: Well, you know, as well as being an ‘art piece’, it’s also actually a functional item. You know, it had to work – we needed it to have lightboxes inside it, it needed to pull apart to have the equipment needed for a performance.

YL: But also it wasn’t just replicating a trunk, it was about using the language of it. Each trunk will be commissioned and after the performance will be owned by someone other than ourselves. The first, which essentially was a blueprint, is owned by Leisure Center. It’s probably playing music right now. We have another HUMAN MAS/CHINE performance planned in London for 2019 and it will be a completely different trunk, in a completely different design. But again, it will be designed to be part of a performance.

AM: So the central piece of design will never be a votive object, will always be built with specific use?

YL: Yes, but it is still also an art piece. And at the same time a juke box, or, you know, a really good hi-fi.

AM: Will there be a narrative thread throughout the performers you’ll work with?

YL: The story is personal in sensibility. It’s a subconscious autobiography. And every one of the performers I’ll work with I’ll go and see perform live beforehand. I want to see and experience what they do physically beforehand. Because otherwise I’d just be a DJ. And of course, I need to see what it is like to be part of their audience – to experience what our own audience would.

“It’s not going to a gig, it’s going to a world” – Olaf Kneer

AM: Because essentially performance art is a contract between the performer and an audience

YL: Right, it’s a collaboration. Otherwise it’s a music video. What makes it performance art is that we are holding people by the hand and taking them into a world we have created.

OK: It’s not going to a gig, it’s going to a world.

YL: It’s not a showcase at Koko.

AM: It’s funny, you can’t ‘measure’ or ‘prove’ art, but in a performance piece you’re getting feedback and critique and evaluation and judgement on all aspects in real time.

YL: Exactly, and that feedback is what makes the performance work. Some people will start at the front and work their way to the back. Some will start at the back and work towards the front – they’re commenting on the art even with their bodies.

AM: Is the audience enjoyment taken into consideration or a by-product?

YL: Their enjoyment isn’t a concern. Their interaction and participation is. They might hate it. But at least they saw it!