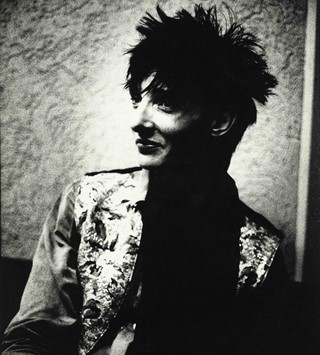

James Crump’s glossy new documentary Antonio Lopez 1970: Sex, Fashion & Disco explores the life and work of an extraordinary Puerto Rican fashion illustrator

- TextStuart Brumfitt

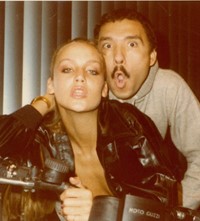

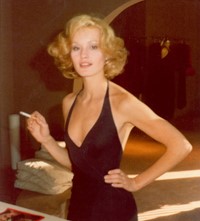

“I had a wild crush on Antonio. Didn’t everybody?” asks actress Jessica Lange, one of the many faces captured by Antonio Lopez in their formative, pre-fame years. James Crump’s film, Antonio Lopez 1970: Sex, Fashion & Disco is heavy on the sex and shows the Puerto Rican-born fashion illustrator as a man/woman magnet with a voracious appetite.

Yes, Lopez had a supreme talent for line drawing, but we see that his greater gift was acting on his attraction to both sexes; talent spotting future beauties who would inspire his fantastical illustrations for Vogue, Harper’s and The New York Times. “He’s this larger than life character that connects,” explains Crump. “It’s pointed out as almost like a paranormal skill, an essential skill of being able to see inside of a person something they are not able to see themselves: an element of beauty, or a personal trait.”

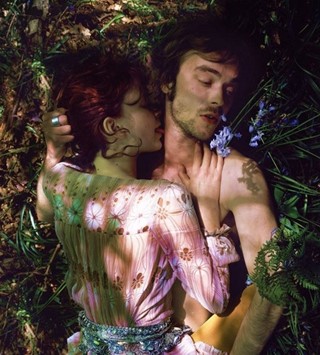

Like his contemporary, Andy Warhol, Lopez was a one-man fame machine, picking out promising party starlets at places like Max’s Kansas City, Studio 54 and Club Sept, then transforming and immortalising them through his imagery. Sex, Fashion & Disco makes you wonder whether people truly desired Lopez, or whether the youthful narcissism at the heart of the scene meant they were mostly in love with being made to feel desired, beautiful and known. Crump sees these things as indivisible – they were both drawn to him and to being drawn by him: “It’s all blended together. The way he’s sitting with the subject and receiving that information, there’s an energy and he’s processing it through his body and it comes out through his hands. To me it’s like a climax, like cumming.”

Former French Vogue editor-in-chief, Joan Juliet Buck equates the desire to create beauty with a sexual urge, Jessica Lange describes the nights being sketched by Lopez as having “a sensuality… an exchange of energy” and Bill Cunningham thinks that the illustrations were “pulsating with sexual desire.” So it’s fitting and funny when Juan Ramos’s former boyfriend, artist Paul Caranicas, points out Lopez’s sex addiction and reveals how he had artistic blocks after long bouts of love-making: “I think he couldn’t draw because of his ongoing sexual affairs, which were nightly and with different people.” Once he’d cum, he couldn’t create.

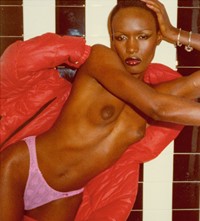

It’s remarkable (and very proto-selfie) to see Lopez’s clique getting endless pleasure out of posing and showing off over so many years. “I think there were dual needs: the subjects needed something and Antonio needed subjects,” explains Crump. Jessica Lange, Pat Cleveland, Grace Jones and Jerry Hall are just some of the figures who went on to even bigger things after a brush with Lopez (sadly Jones and his one-time fiancée Hall didn’t take part in the film – their thoughts would have been telling).

Everybody wanted a piece. “There was a lot of competition trying to get close to Antonio,” Cleveland says in her cutesy drawl. Even after his death, the interviewees’ tales unwittingly battle it out over who knew him best and, bluntly, who had the greatest sex with him. Eyes roll as they remember all the orgasmic action – actress Patti D’Arbanville’s bouncy bed hair and blissed-out daze make it look she’s come fresh from a romp with him. “I was crazy in love with him, absolutely,” she coos. “I remember everyone falling in love with Antonio. You couldn’t meet him and not fall in love with him. He was an incredible flirt… Nobody was spared from his charm.”

“When you were next to him, you felt like dancing,” says Cleveland. “So much of Antonio was the way he stood and the way he danced – everything was fluid,” adds Buck. D’Arbanville says they would dance together “and then there was a natural progression to the bed… he was very talented with his hands and with his eyes.” At times the film’s praise seems too fawning, but Crump insists, “So many people genuinely loved Antonio, it was hard to get anyone to say anything negative about him.”

Lopez and his early boyfriend and creative partner Juan Ramos had no taboos or boundaries. “Those kids went dancing and went sleeping with whoever they wanted. It was wonderful!” according to Cunningham. “Antonio and Juan were the most liberated… You can’t imagine the intrigue, but it was charming – charming because it was absolutely harmless.” Of course this was in the 1970s, which Crump characterises as “a very liberated time.” After the civil rights struggles of the ‘60s and before the horrors of the ‘80s AIDS epidemic, “there’s this moment of pleasure… almost a utopian moment of freedom.” By all accounts no-one was enjoying the spoils more than Lopez: his friend, artist-slash-restaurateur, Michael Chow says, “Antonio is completely free and also, he’s bisexual, so he’s even freer.”

Make-up artist Corey Tippin says Lopez’s sexuality “was way biased towards men, but he slept with many, many women too and totally appreciated women and they loved him back.” Many of Lopez’s lovers – Tippin included - would eventually end up falling for Ramos, who Buck describes as “short, anguished, intense” and who was the perfect foil to Lopez, the flamboyant frontman who created a whirl around him from New York to Paris to Tokyo.

Sex, Fashion & Disco is a celebration of Lopez’s illustrations and a snapshot of a scene, but mostly, it’s a portrait of a man way ahead of his time. “He was able to somehow see what the future could possibly look like: an open society,” says Crump. “He wasn’t hung up on any notion of identification. He didn’t care. First and foremost, he wanted freedom to do whatever he wanted to do.”

Sex, Fashion & Disco is in cinemas now.