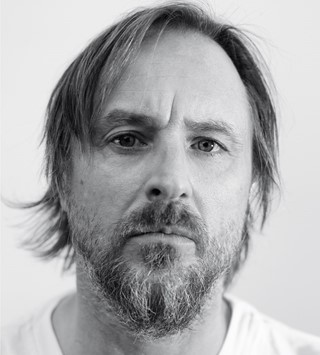

Rob Nowill questions how the #MeToo movement might affect men’s fashion

- TextRob Nowill

Is there anything less appealing at this moment than being thought of as a ‘man’s man’? After Trump, after Weinstein, after Spacey, and after and all of the other toxic sludge that emerged over the course of the past year, it’s hard to imagine there’s anyone left in the Western world for whom masculinity is the ideal.

This is posing an interesting question for menswear designers. As the men’s shows roll on to Milan and Paris, Vogue Runway articulated it neatly last week: if fashion should mirror the cultural moment, how do you create men’s clothes when manliness itself is viewed as synonymous with exploitation, arrogance, greed and stupidity? Certainly, the fashion brands that are still clinging to an idealised vision of masculinity feel out of step with the times: even Mr Porter, which was built on an image of mid-century gentleman’s clubs and perfectly-folded pocket squares, has inched away from its former aesthetic towards something less neatly starched.

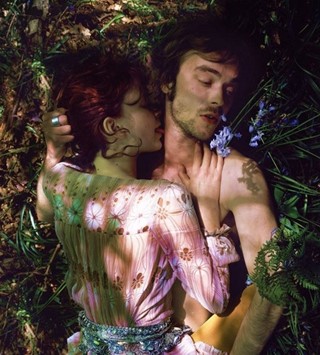

What’s more, the menswear brands that flourished in 2017 did so either by abandoning conventional ideals of manliness. Gucci’s men looked like Gucci’s women, festooned in a mish-mash of sequins, embroidery, and lurid colour. Balenciaga – the other label which dominated the cultural conversation – satirised the restrictions of traditional menswear, presenting outsized and distorted takes on shirts, ties, and tailoring, stamped with corporate logos. And the biggest breakout designers of the past year were unified by a willingness to challenge normative ideas of gender, from Grace Wales Bonner’s quietly intellectual reframing of masculinity to to Telfar Clemens’ athletic take on androgyny. Both moved beyond being media darlings, racking up stockists, winning awards, and forcing even the most conservative critics to take them seriously.

“If fashion should mirror the cultural moment, how do you create men’s clothes when manliness itself is viewed as synonymous with exploitation, arrogance, greed and stupidity?”

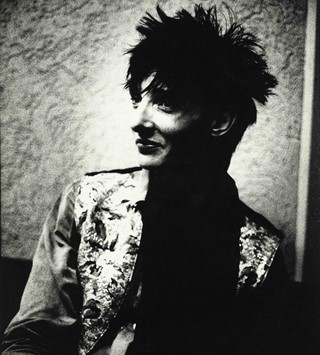

Alexander Fury, the fashion critic and editor of AnOther, sees a parallel between now and the gender-bending fashions of the late 1980s. “Both periods are playing against an overarching mood of political conservatism,” he says. “Boy George and the flamboyance of Westwood emerged at the height of Thatcherism, just as our current opulent moment is a counterpoint to Trump and Brexit. Perhaps it’s because men in suits are now the bad guys.” To Fury, this can only be a positive: “I don’t think that masculinity itself has become unfashionable. The more exciting thing is that its meaning is being challenged.”

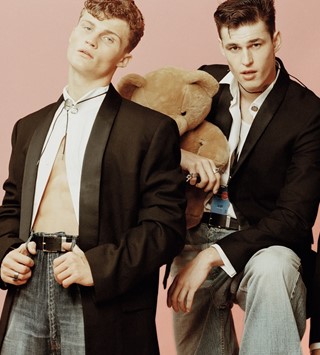

Christopher Shannon, who elected not to show this season, is among the designers rethinking what masculinity signifies to him. “I’m not sure what it means any more. Traditional masculinity always feels a bit Guy Ritchie to me,” he explains. “It’s like a kind of bunting nostalgia for a time I don’t think ever really existed.” His collections, increasingly, seem at once to celebrate and parody the tropes of masculinity: baggy denim erupts into bursts of frills; tracksuits snake around the body like a cocktail dress; and sports shorts are cut to the proportions of hotpants. It’s this tension that he relishes. “I think a lot of my choices are informed by my loathing of male clichés,” he explains. “But I’m not interested in overplaying gender. For me, the interesting point is the in-between.”

“Boy George and the flamboyance of Westwood emerged at the height of Thatcherism, just as our current opulent moment is a counterpoint to Trump and Brexit” – Alexander Fury

Is there a risk, though, that setting traditional masculinity afloat could make the men’s collections themselves redundant? Already, ever-increasing numbers of fashion brands (including Calvin Klein, Burberry and Bottega Veneta) are scrapping their dedicated men’s shows, choosing instead to elide their women’s and men’s collections into a joint catwalk. And, though the concept of ‘gender-neutral’ clothing has been overused to the point of meaninglessness, it showed that there is a market for less obviously gendered clothing. Simon Chilvers, men’s style director at MATCHESFASHION.COM, has seen unisex clothing meet a strong reaction from consumers. “Brands like Gucci have shown that clothes no longer have to be aimed at only one gender,” he says. “And their success shows that there’s a generation who no longer care about traditional gender codes when it comes to fashion.” So isn’t it possible that the aesthetics of traditional menswear could fade into irrelevance?

Personally, I’d like to see more designers prod, probe and play with the stereotypes of manliness. The Milan shows are next, and many of the city’s designers have followed Gucci into ever-increasing embellishment and opulence in their recent men’s collections. But I’m nostalgic for the Milanese shows of the early noughties, which presented a thrumming, virile vision of full-blooded testosterone. It was masculinity, as presented through prism of gay male desire. It turned the straight man into a sex object. It felt raunchy, and almost subversive. Versace, in particular, was once notorious for its unabashed celebration of male flesh. Perhaps Donatella could be the one to show us how to enjoy masculinity again: by giving it all the irreverence it deserves.