Stanley Booth’s Encounter with Elvis

- TextSean OHagan

As rock’n’roll’s greatest chronicler, Stanley Booth has spent much of his life on the sharp edge of excess and destruction. Here, from a new collection of essays, are two of his close encounters...

Taken from the A/W19 issue of Another Man:

If, as they say, a man is known by the company he keeps, Stanley Booth is lucky to be alive. Now 77, he counts Keith Richards as a longtime friend, having fallen under his sway while covering The Rolling Stones’ 1969 tour of America. Booth’s time with the Stones began just before the death of Brian Jones in July of that year and ended with the deadly violence that attended their infamous free concert at the Altamont speedway in northern California in December. “You really had the feeling you could die the next minute,” Booth told me in 2012, referring to the spiralling chaos of a concert that was ‘policed’ by Hells Angels wired on booze and speed.

When the tour finished, he returned to London with the Stones, spending several months living in Richards’ house. “We did indulge in some daredevil behaviour,” he recalled, matter of factly, “but, finally I realised I was going down a road that could lead to my destruction.” He returned to America, chastened but not clean. That would take another decade or more. Likewise the completion of his now classic book, The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones, finally published to critical acclaim in 1984. When I asked Booth why it took so long to write, he replied: “I had to become somebody different from the person who went on the tour… I had to devise a new persona in order to tell the story.” It was worth the wait. The book’s novelistic style perfectly evoked the dissolute glamour of the group. It was hailed by Keith Richards as “the only one I can read and say, ‘Yeah, that’s how it was’.”

Since then, Booth’s output has been fitful but never less than intriguing, his writing a mixture of deep, often first-hand knowledge and undimmed passion. Inevitably, a biography of Keith Richards appeared in 1996, knowingly subtitled Standing in the Shadows. It referred to the life and musical role of the musician, but could just as easily have applied to Booth himself. He is an acute observer but not a detached one, his best work often infused with the sense that he is recalling a time, a place or a style of music that is past, or in the process of passing into history.

Now, after another long interregnum, comes Red, Hot and Blue. It comprises 26 essays, painstakingly crafted and well-wrought. This time around, the subtitle could be his own defiant elegy: Fifty Years of Writing About Music, Memphis, and Motherfuckers. The book is dedicated to the wayward Memphis legend Dewey Phillips, whose hyper-charged 1950s late-night radio show first broadcast raw rhythm & blues to a new postwar listening public mainly made up of young, restless teenagers. Dewey was the first DJ to play Elvis Presley’s debut single, That’s All Right Mama, and to alert his enthralled listeners to the fact that the young, unknown singer was, in fact, white. “He may have been crazy,” Booth writes of Dewey, whose unhinged rock‘n’roll spirit and doomed life pervades the entire book, “but he was a genius and very like a saint.” He was also, like Booth, an outsider, a country boy in thrall to black rhythm & blues and the primitive boogie made by wired white kids like himself who poured their demons into countless rockabilly records. Booth hailed from the rural swamplands of Waycross, Georgia, where country rock visionary Gram Parsons also grew up. It was an insular community even by the standards of the deep south. “People around Waycross think of Atlanta the way you and I think of the moon,” Booth later wrote. After a spell in Macon, Georgia, his family settled in Memphis, where he befriended – and wrote about – local bohemian hellraisers like the legendary photographer William Eggleston and the maverick musician-producer Jim Dickinson. Memphis looms large in Red, Hot and Blue: his astute and wildly anecdotal essay Situation Report: Elvis in Memphis, 1967, begins with the words, “Talking about eating pussy...” and continues with a tantalising mention of Elvis’s carnal tryst with the young Natalie Wood.

It was at Graceland that Booth overdosed on Darvon, an opioid painkiller given to him by the perpetually wired Dewey, his entrée into the court of the King. Later, in 1979, he interviewed, befriended and became a patient of Dr. George C. Nichopoulos aka ‘Dr. Nick’, who had previously been Elvis’s personal physician. Red, Hot and Blue could be read as 26 meditations on the blues according to Stanley Booth, with his own wayward life as the connecting thread. As well as being a deeply personal take on the people and places that once inhabited, and defined, rock‘n’roll and its myriad musical precedents, it is also an autobiography of sorts. The writer is present, palpably so, in every portrait he paints of these charismatic, messed up, visionary characters. We will not see their like again. Nor his.

ELVIS IN MEMPHIS, 1967

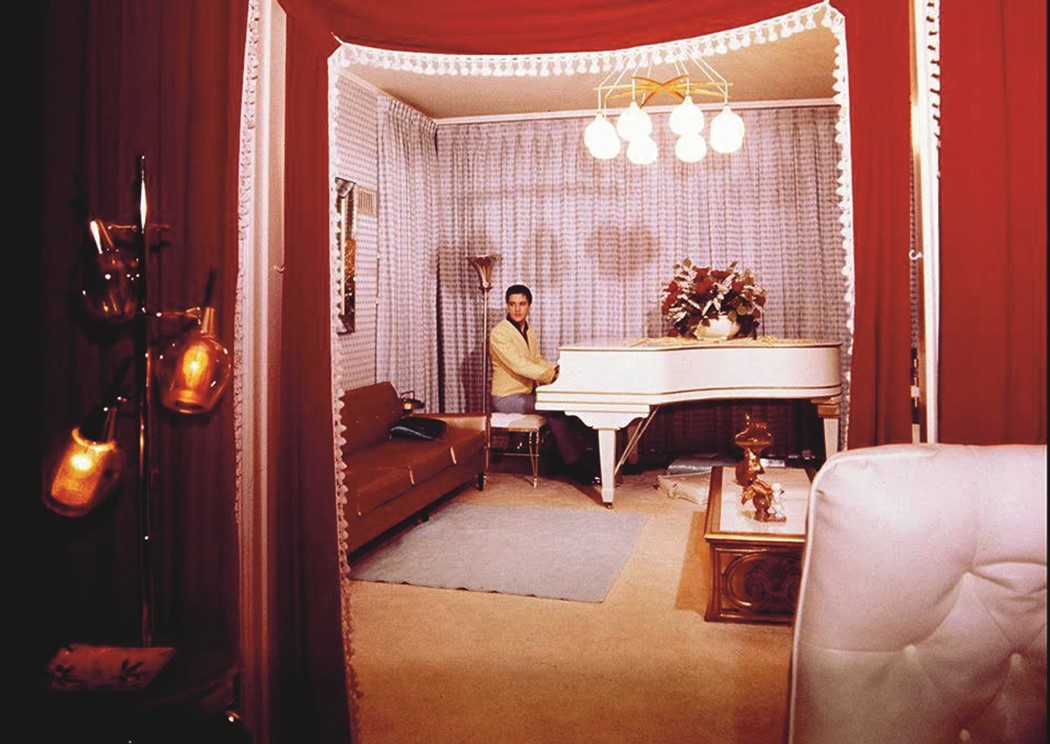

On a day not so long ago, when Presley happened to be staying at Graceland, the house was crowded with friends and friends of friends, all waiting for old El to wake up, come downstairs, and turn them on with his presence. People were wandering from room to room, looking for action, and there was little to be found. In the basement – a large, divided room with gold records hung in frames around the walls, creating a sort of halo effect – they were shooting pool or lounging under the Pepsi-Cola signs at the soda fountain. (When Elvis likes something, he really likes it.) In the living room boys and girls were sprawled, nearly unconscious with boredom, over the long white couches, among the deep snowy drifts of rug. One girl was standing by the enormous picture window, absently pushing one button, then another, activating an electrical traverse rod, opening and closing the red velvet drapes. On a table beside the fireplace of smoky moulded glass, a pink ceramic elephant was sniffing the artificial roses. Nearby, in the music room, a thin, dark-haired boy who had been lying on the cloth-of-gold couch, watching Joel McCrea on the early movie, snapped the remotecontrol switch, turning off the ivory television set. He yawned, stretched, went to the white, gilt-trimmed piano, sat down on the matching stool, and began to play. He was not bad, playing a kind of limp, melancholy boogie, and soon there was an audience facing him, their backs to the door.

Then, all at once, through the use of perceptions which could only be described as extra-sensory, everyone in the room knew that Elvis was there. And, stranger still, nobody moved. Everyone kept his cool. Out of the corner of an eye Presley could be seen, leaning against the doorway, looking like Lash LaRue in boots, black Levis and a black silk shirt.

The piano player’s back stiffens, but he is into the bag and has to boogie his way out. “What is this, amateur night?” someone mutters. Finally – it cannot have been more than a minute – the music stops. Everyone turns toward the door. Well I’ll be damn. It’s Elvis. What say, boy? Elvis smiles, but does not speak. In his arms he is cradling a big blue model airplane.

A few minutes later, the word – the sensation – having passed through the house, the entire company is out on the lawn, where Presley is trying to start the plane. About half the group has graduated into the currently fashionable Western clothing, and the rest are wearing the traditional pool-hustler’s silks. They all watch intently as Elvis, kneeling over the plane, tries for the tenth time to make the tiny engine turn over; when it splutters and dies, a groan, as of one voice, rises from the crowd.

Elvis stands, mops his brow (though of course he is not perspiring), takes a thin cigar from his shirt pocket and peels away the cellophane wrapping. When he puts the cigar between his teeth a wall of flame erupts before him. Momentarily startled, he peers into the blaze of matches and lighters offered by willing hands. With a nod he designates one of the crowd, who steps forward, shaking, ignites the cigar and then, his moment of glory, of service to the King, at an end, he retires into anonymity. “Thank ya very much,” says Elvis.

ELEMENTARY EGGLESTON

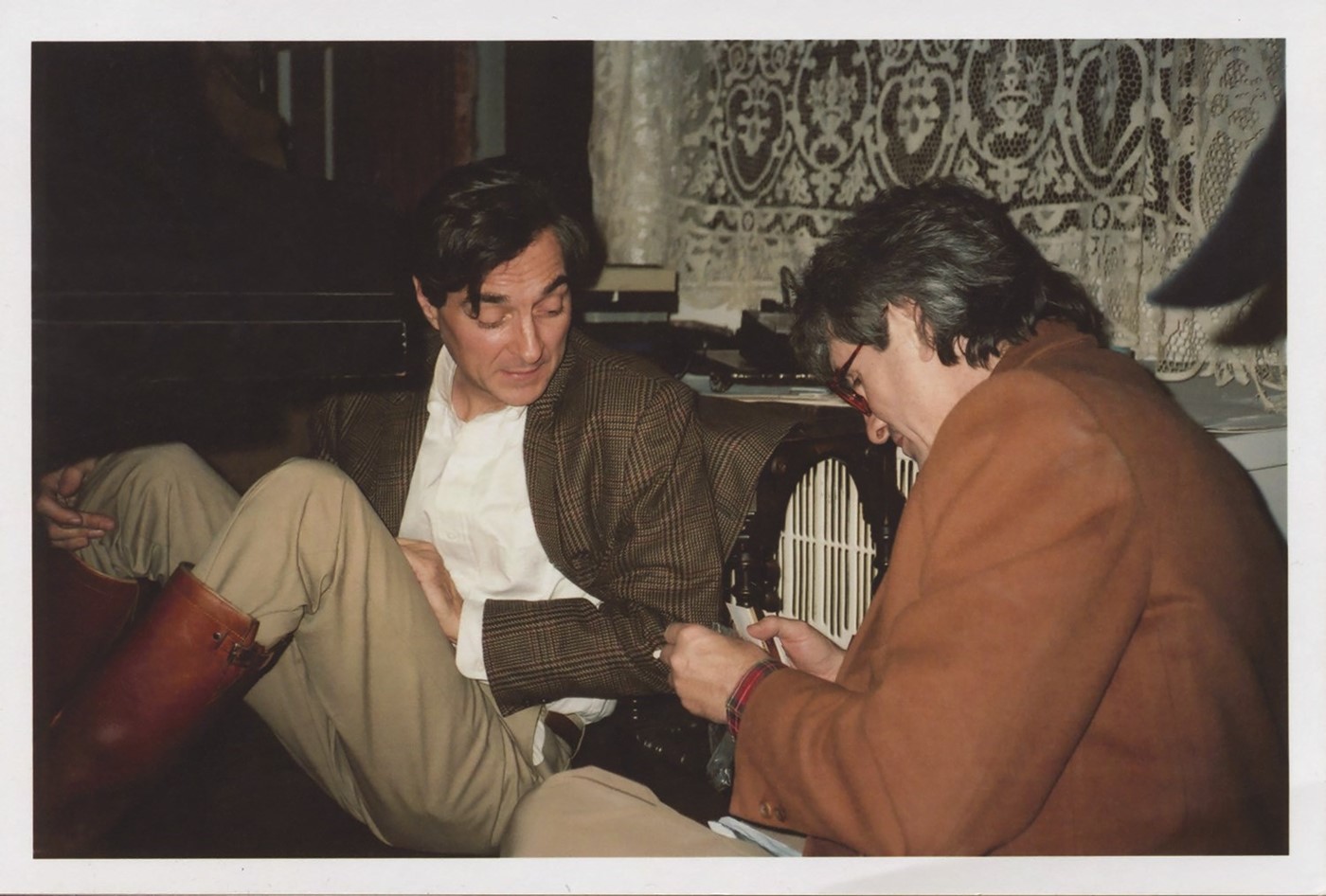

“The murder is always in the past,” William Joseph Eggleston said, leaning over the bar, speaking in a conspiratorial tone to my right ear. It was about 11 o’clock, and the Lamplighter, on Madison Avenue in midtown Memphis, glowed like a dim bulb. The three other men sitting on the black leatherette bar stools wore bill caps, two with slogans: “Everybody’s goodlookin’ after 2AM” and “This is my PARTY cap”. Jim Reeves was singing, “Put your sweet lips a little closer to the phone...”

Eggleston and I were out of the Lamp’s sartorial swing, me in Irish tweeds, him in a four-button glen plaid jacket, knee-high English riding boots, and a full-length Nazi SS overcoat. (“This town is no place to wear a Nazi uniform,” one of his Memphis friends said, and another answered, “I should think it would be the safest place in the world.”) Eggleston wears the coat not out of Nazi sympathies but a kind of fierce irony that seems remarkable in such a sweet-tempered man. When Hitler’s name chanced to come up in one of our conversations, Eggleston quoted Sir Christopher Wren’s epitaph: “If you seek his monument, look around.”

Eggleston went on: “The first thing you know in the dream is that you’ll have the killing hanging over you for the rest of your life.”

“I never kill anybody I’d really like to kill.” “Me neither.” “Do you have precognitive dreams?” “I have a thousand déjà vus a day. But when I’m asleep, I’m in a world quite removed from me, with moving lights and perfectly contoured shapes. As a child I had a recurring fever dream with a fine thread of something, like a silver ribbon, running at a speed so high it looks like it’s sitting still – then it starts getting a little messed up, then it goes into whole galaxies of confusion, then, at last, because there’s no conceivable way out, it’s a complete debacle. They’re the worst ones.”

“Nightmares?” “Dreams. Sometimes the silver thread straightens itself out – feels pretty good.”

In the Lamp’s men’s room, things bite you on the legs and light in your hair. “Shirley, could we have a couple of beers?” Eggleston had asked the dour, dumpling-shaped bartender as we came in.

“Don’t wear my name out tonight,” Shirley had said, moving slowly toward the cooler.

I came out of the men’s to find Eggleston, having spilled his drink, asking Shirley for a Kleenex “to blow my nose”. The front wall of the Lamp had been rearranged a few days earlier by a young man who’d attempted to drive a stolen rental car through it. “I guess he wanted curb service,” Shirley said.

More people had come in. “Every day is a good day,” a man at the left end of the bar, near the jukebox, was saying. A girl sitting near the middle of the bar said, “I can’t help it if you don’t like my gay friends” to the man in the party cap. At the far right a white-haired man was finishing a beer. “I’m ’on have one more and go home,” he said.

“All right, Vern,” Shirley told him. “Hard to believe how simply we started,” Eggleston said as I sat down.

Excerpts from Red Hot and Blue: Fifty Years of Writing about Music, Memphis, and Motherfuckers by Stanley Booth, presented with permission from Chicago Review Press.