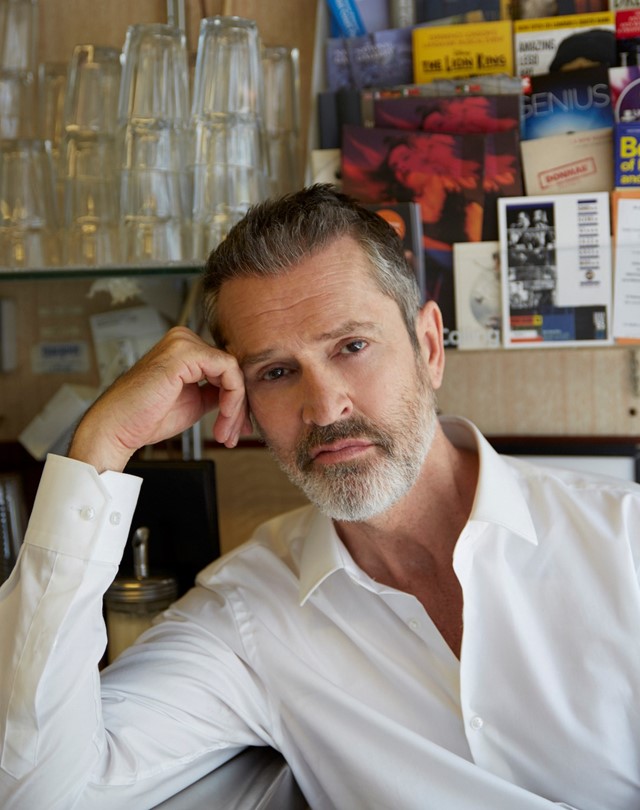

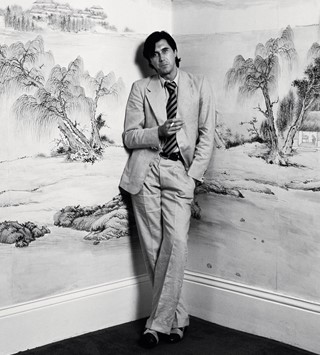

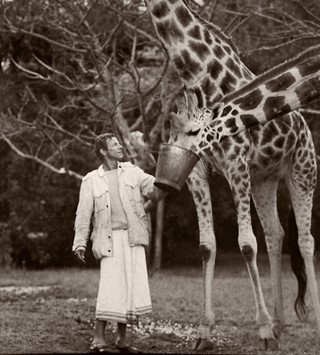

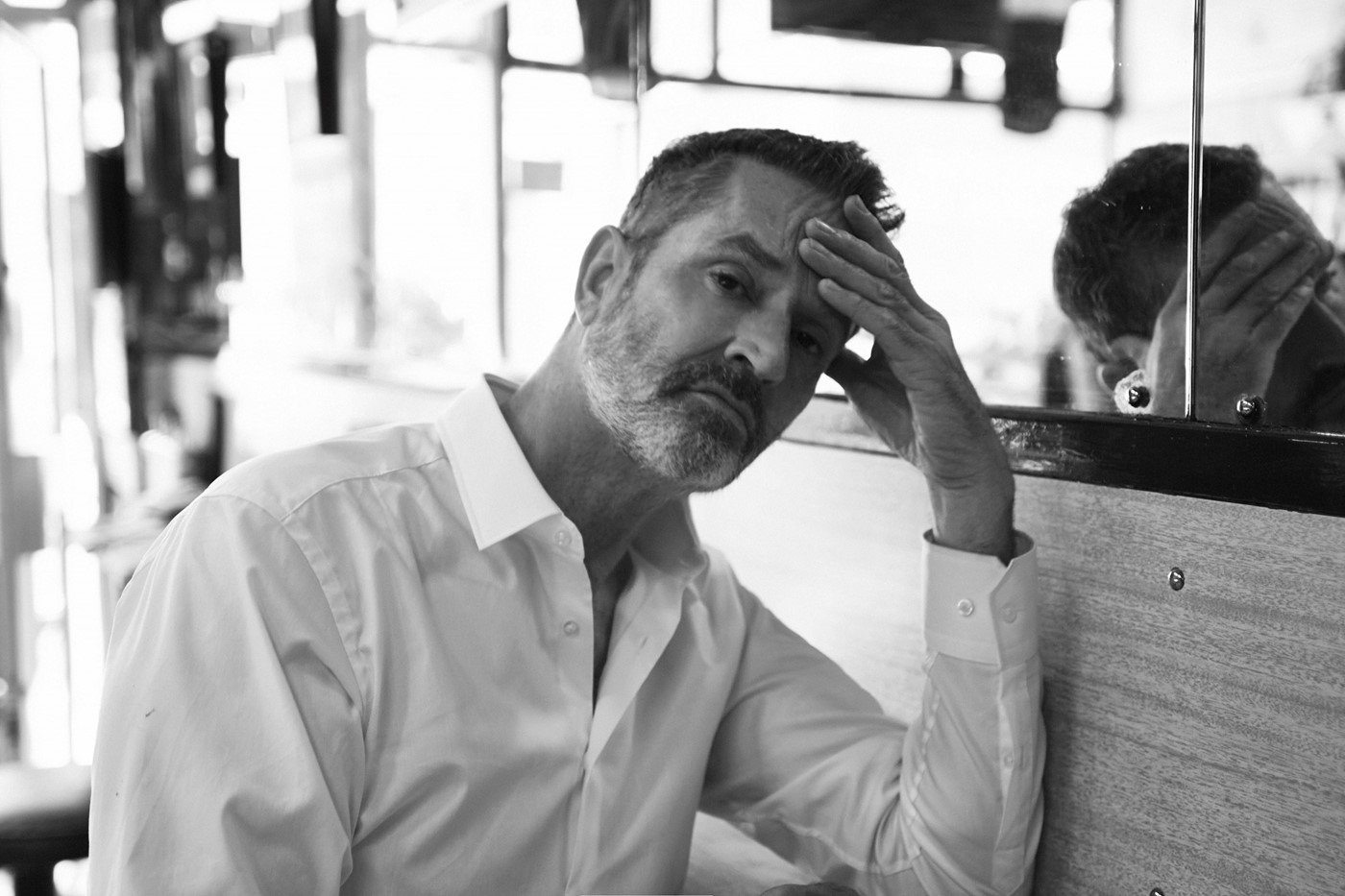

Rupert Everett: ‘Oscar Wilde Is the Patron Saint of Homosexuals’

- TextHynam Kendall

As his Oscar Wilde biopic hits cinemas, Everett opens up about his relationship with the legendary writer and explains why he is so important – especially to LGBTQ+ people working in the ‘aggressively heterosexual’ world of show business

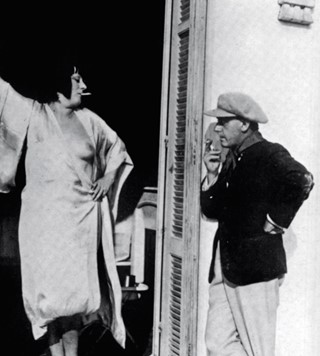

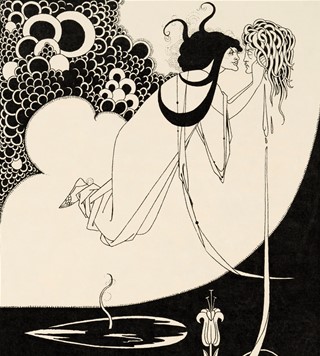

In the film The Happy Prince – Rupert Everett’s ten-year passion project in which he writes, stars and for the first time directs – Oscar Wilde careens side-streets doused in urine and alcohol, his face inelegantly painted and slipping away as rent boys, former fans and homophobes berate him, spit on him and demand payment of debt. It is a Wilde we have never seen before – his unsanitised, waning and, as Everett demurs, “utterly romantic” final years. Here, speaking to Another Man, and coinciding with the film’s release tomorrow, Everett details his lifelong relationship with and affinity for the legendary queer writer.

“I was first introduced to Oscar Wilde as a child. I was six, or maybe even seven. I remember very clearly the experience of my mother reading me his children’s story, The Happy Prince. I remember her, I remember the act of her reading it and I remember the feeling that it gave me, perhaps more than the actual story itself.

“There was no Wilde at school for me – I went to a monastery, so as a gay writer he certainly had no place on the syllabus. The other greats, yes, but not Wilde. At drama school we had a Wilde term – I was in Lady Windermere’s Fan – though it didn’t particularly excite me, or any of us at the time. It didn’t feel ‘exciting’ in that way that you want everything to feel ‘exciting’ when you’re young. But, little by little, he trickled into my life.

“I was in a production of The Portrait of Dorian Gray at the Glasgow Citizens’ Theatre in 1989, I would have been 30, and it ended up being a very successful production. That’s when – as an actor at least – I started to feel an affinity. I saw that I was good at it – the wordplay, the language. And then followed The Importance of Being Earnest in Paris, at their national theatre. I acted it completely in French. I really don’t know why I kept falling into his plays, but then it was films of his work too. There was The Importance of Being Earnest and An Ideal Husband, both very large films with all-star casts. And then I suppose by that point I was very much rooted to him.

“When I was thinking of writing something for myself, a Wilde project seemed like the right thing to do. I don’t think it was born necessarily of a fascination with him; he had just become part of my landscape.

“I always wondered why Wilde in exile hadn’t been done before – those three years between release from Gaol and death. All the existing Wilde films went up to the moment he went into prison but no further, because filmmakers wanted to treat him with kid gloves. They didn’t want him looking like he smelt of piss. It was virgin territory in a way, and as a result has been very surprising for people watching my film; people whose experience of him before this had been too reverential. Wilde was the 19th century’s last great vagabond.

“All the existing Wilde films went up to the moment he went into prison but no further, because filmmakers wanted to treat him with kid gloves. They didn’t want him looking like he smelt of piss”

“My film, The Happy Prince, is what made my relationship with Wilde feverish. You must understand, there were other factors involved in that feeling, why I felt like that. I was working on this film at a time in my life when I wasn’t getting work, really. I was getting older. Those factored into my changing relationship with Wilde. That helped the ‘fever’.

“It’s been a ten-year journey making The Happy Prince, and there have been doubts along the way, of course. At the very beginning, the producer Scott Rudin said he loved the script I wrote, but for a Philip Seymour Hoffman vehicle. For Philip to play Wilde. I said no. Only once did another actor get suggested for the lead role. After that, after I said no to Philip, I don’t think anyone wanted to make it. And when I couldn’t get funding, I did regret that decision at certain points.

“What I really wanted was to show audiences that I could be Wilde. For whatever reason, potential backers couldn’t see it. I had to prove myself. So I worked on a stage portrayal of Wilde, which turned out to be David Hare’s The Judas Kiss. Luckily critics said it’s the best thing I’d done.

“The transformation into him came little by little. Perhaps my acting life before was preparation – doing all those plays and films of his works. When the theatre made me a bodysuit to play him, that was the really transformative moment for me – that silhouette, that sort of elephantine quality that it gave me when I put it on. I wore the same bodysuit in the film.

“I often say he is the patron saint of homosexuals. Especially for those of us in show business, which is run by heterosexual men and can be at times aggressively heterosexual”

“Obsession isn’t the right word. You can be obsessed with matinee idols – Marlon Brando, James Dean – but my interest in Wilde is more profound than obsession. I often say he is the patron saint of homosexuals. Especially for those of us in show business, which is run by heterosexual men and can be at times aggressively heterosexual.

“I firmly believe the gay liberation movement dates back to Wilde. Because of Wilde the notion of homosexuality came into debate, internationally. The discourse about same-sex relations really started with him. I think that’s why he has a bearing on all of our lives within the LGBTQ+ community, it’s much deeper than fandom, much deeper than him being ‘iconic’ – god I hate that word. His life is a punctuation point for us, and the start of something.

“Coming to London in 1975, we’d only been legal for seven years and gay clubs were the new world. I was free to be openly gay and I took the opportunity to do so. But the law being so new meant it was fairly shadowy, especially regarding public versus private displays of homosexual behaviour. And what that meant practically for us was that the police continued harassing gays and raiding clubs and chucking everyone into paddy wagons and taking them into the station. So the whole notion of Wilde’s queer experience was still very much alive then.

“We say this isn’t the queer experience now, but that’s only here. In the rest of the world, the Wilde-ian queer experience is still going. In The Happy Prince we show Wilde chased in the streets by men holding weapons, being spat on, reviled. This still happens in the world to our community.

“In the rest of the world, the Wilde-ian queer experience is still going. In The Happy Prince we show Wilde chased in the streets by men holding weapons, being spat on, reviled. This still happens in the world to our community”

“I call this film romantic. I call this period of Wilde’s life romantic. Because it is romantic. Up until the 90s, in the pre-Freudian world, all types of suffering and trouble and struggle were considered romantic. And necessary. Suffering in love, for example, is not really a notion that anyone embraces wholeheartedly anymore, whereas up until 30 years ago people jumped over cliffs to suffer in love. Now people are getting more practical about things I suppose.

“Wilde’s genius was variable, I’ll be honest. I think The Importance of Being Earnest is, for example, a work of genius. But a lot of his work isn’t. It’s clever. But there are a lot of other writers that were doing similar. I think it’s the entirety of him, including the flaws, that constitute his genius. That perhaps make him even more so. And he is a genius. Flaws and all.”

The Happy Prince hits UK cinemas June 15