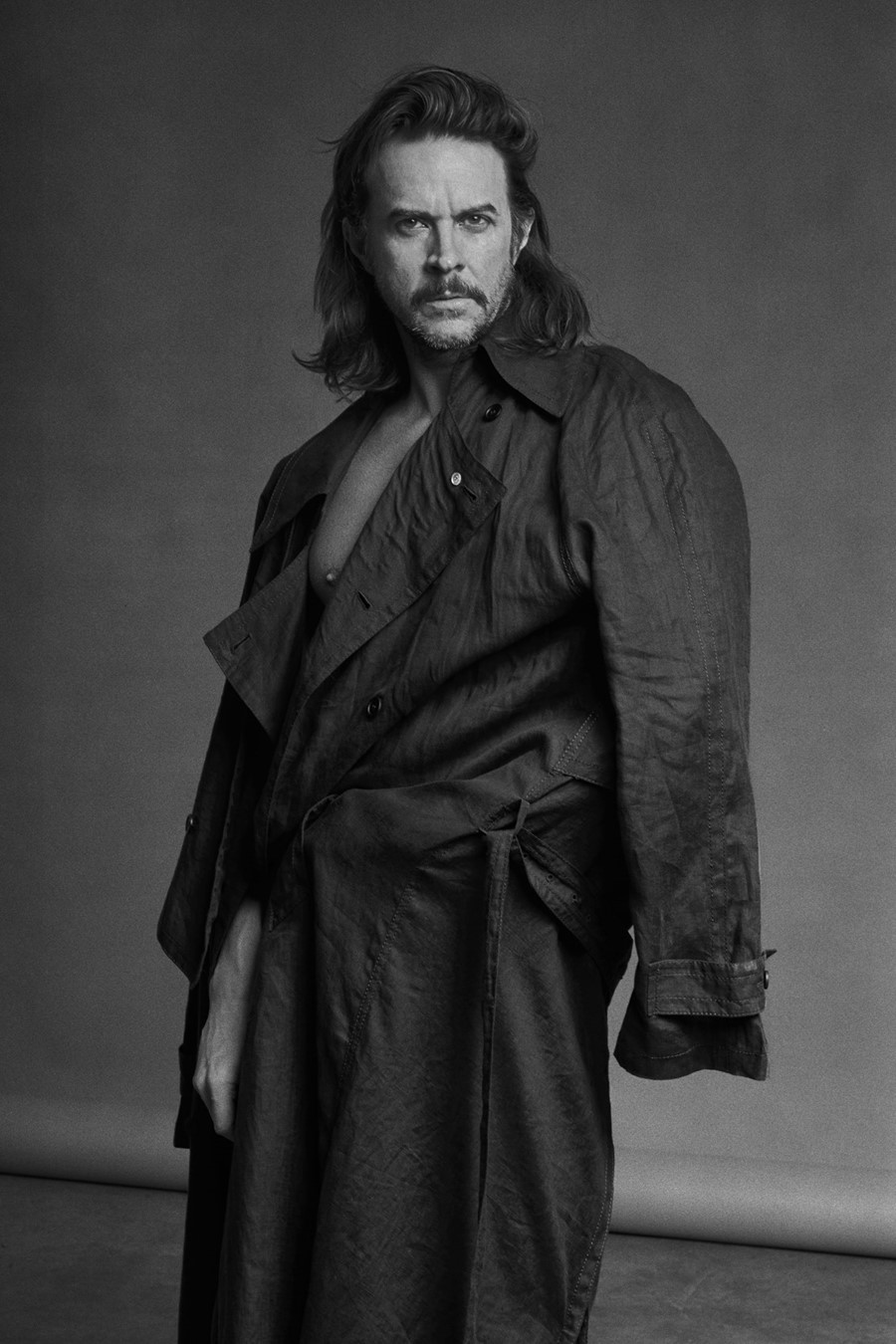

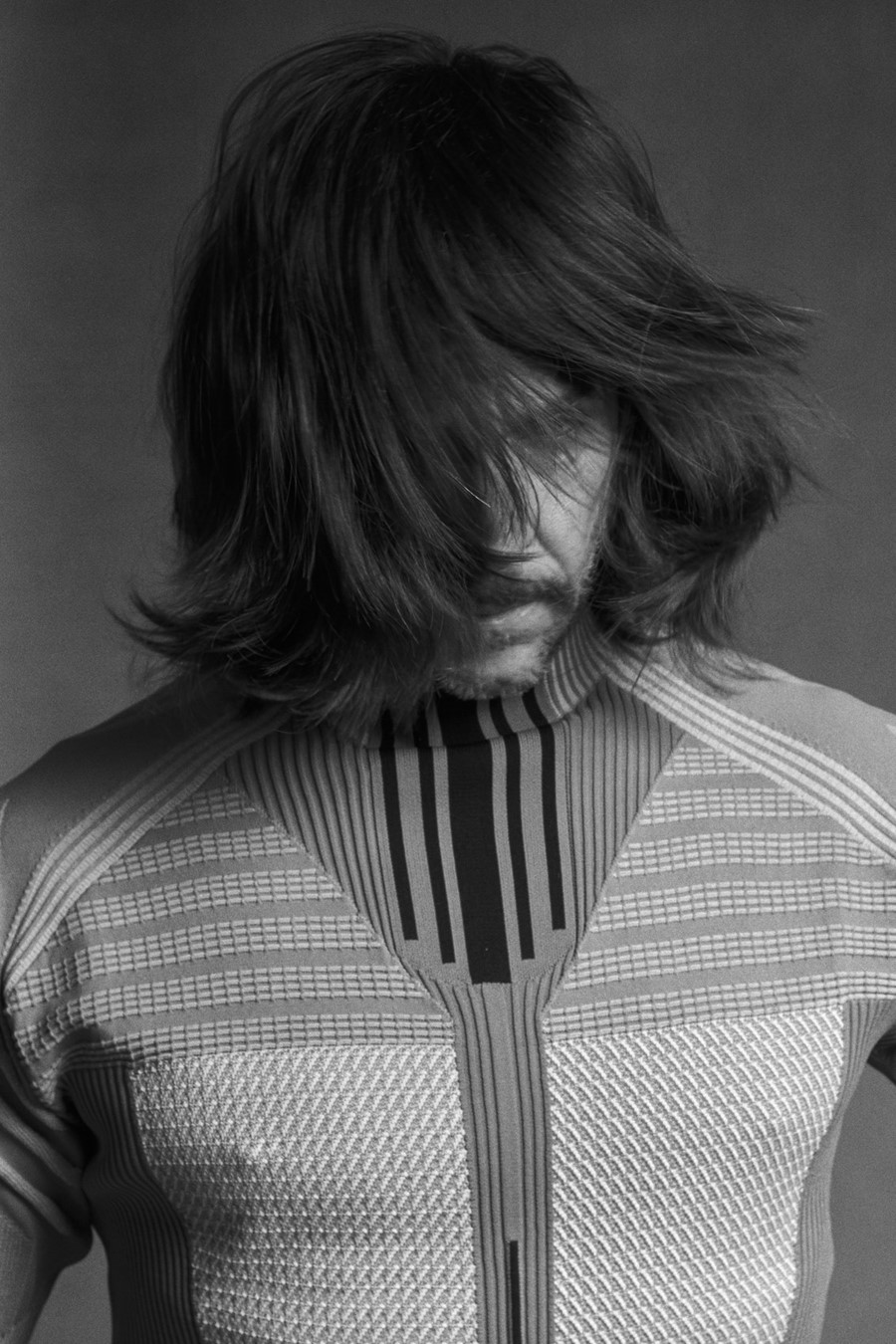

In Conversation: R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe and Fischerspooner’s Casey Spooner

- TextTom Connick

First lovers, then collaborators, Stipe and Spooner’s relationship began in the 80s and, nearly 30 years on, has birthed a record – here, the pair open up about this journey and Fischerspooner’s new album, Sir

On paper, R.E.M. and Fischerspooner seem like unlikely bedfellows. Through the late 90s and early 00s, Fischerspooner’s flamboyant, sardonic art-pop eschewed convention at every turn, fuelled by the lip-synched performances of Casey Spooner, while R.E.M.’s soaring indie-rock became a vessel for frontman Michael Stipe’s innermost emotional turmoils. Roll back the clock 30 years, though, and another story begins to emerge.

Lovers in the 80s, Stipe and Spooner’s tale begins on the brink of R.E.M.’s explosive success. From then, the pair maintained a friendship, through fame and familial issues, to relationship breakdowns and beyond. It’s a three-decade-long relationship like no other; one that still fizzes with mutual respect today, as the pair finish each other’s sentences from across the Atlantic – Stipe in New York, Spooner in Paris.

Fischerspooner’s new album, Sir, was produced by Stipe in the house he and Spooner once shared, and documents the collapse of Spooner’s long-term relationship and subsequent sexual reawakening. It’s a brilliant fusion of both creative minds. Here, Another Man catches up with the duo, who discuss their personal histories, creative differences, and eating gruel at writing sessions.

Let’s start at the beginning – how did you guys first meet?

Michael Stipe: We met in ‘88 and hooked up and then Casey went off to art school. We saw each other from time to time in the 90s and then Fischerspooner started and I was like ‘this is amazing!’. I’d see them perform and Casey would send me pictures of what they were doing. I never imagined that 30 years later we’d be chatting about a record we’d worked on together. That’s just wild.

Casey Spooner: Never – I never imagined that.

MS: We love each other, he’s amazing and he’s one of the bright lights of my life.

CS: We’re family!

How did things progress from there?

CS: I saw Michael a little bit, but not a lot. He was really busy in the 90s. He was working a lot so I’d bump into him every so often. We crossed paths once in LA and a little in Vancouver. I see Michael more now than ever before.

MS: Yeah. The work we’ve done together over the past couple of years came at an interesting point in both of our lives. We were both going through these cataclysmic personal times and this record was the distraction we needed to get through them. It was a way for us to step out of our lives which, in one respect or another, [were] falling apart or crumbling very dramatically in ways that neither of us had anticipated.

You met so long ago, but at such formative times in your lives. Casey, you were about to go to school. Things were picking up with R.E.M. It feels like you met each other at an important time.

CS: It was a turning point, we always meet at turning points.

MS: You’re right. I’m not going to move to Paris though! [laughs]

CS: Well no, but you've returned to music. That’s a big thing.

MS: After R.E.M. disbanded, I had to step away from music for some time. I had no idea how long. I didn’t expect that helping Casey in the studio on a couple of songs would bring me back into it. I had a five-year break where I didn’t have to think about music at all. That was great, it made me really hungry. Music for me, it’s all-encompassing, and like a giant filter that blocks out everything else. It’s all I want to focus on. Doing that for the best part of my life was pretty overwhelming.

CS: I don’t know, I tend to bounce around. My inspiration comes from adventure and writing stories, so going back and forth and making a picture, a song, a story, a film. I work simultaneously.

Do you think coming from those two different creative sides helped bring you together? Opposites attract, as they say.

CS: I don’t know. It took us both by surprise and happened quite accidentally. I thought I was done with the record and Michael was just helping me with the last song – it was a really difficult piece of music but he knew how to attack [it]. He was just ‘song doctoring’ on a few songs. Everything snowballed. It wasn’t something that I’d anticipated or that he’d planned.

MS: Casey, here’s an interesting question. Having said that, and gone down the path we went, could you imagine the record you had before coming out as a separate entity from Sir?

CS: You know what’s funny? I used to carry a little Post-it in my wallet with all the working song titles. I have it somewhere in storage in the Bronx now. It would be amazing to go back and cut some of those songs and re-approach them with the team we have in place now. I really wish I could remember what the songs were. I can’t even remember half that record.

MS: It’s a complete narrative.

CS: It’s kind of a complete piece. That was a rarity because it’s hard to work alone. You need that perspective to help guide you. You’re the first producer that I’ve worked with that came more from performance and songwriting – a lot of times producers came in with their way, more from the technical aspect of programming and sonic perspective.

MS: I can’t even turn on the lights. I’m not that technical.

CS: I’m exactly the same. I can’t do anything without an engineer.

Was it nice to be able to come together again?

MS: Casey has always been insanely supportive of anything that I wanted to do, particularly outside of music. R.E.M. wasn’t really Casey’s cup of tea, but he recognised what I was doing from a performative aspect and the work that went into it.

CS: Yeah, it was a great experience for me, because I thought I was going to be a painter and I wasn’t heading towards performance at all. When we were together when I was 18, I watched you make music videos, pick the backdrop for your television appearances and hire people to make your costumes. I never realised that a decade later, I’d be involved in the same sort of processes. It was interesting – in 1988, I saw you do what I ended up doing in 1998. I ended up falling out of painting and into experimental theatre and then into film, out of film and into music. It was ironic that I ran as far away as I could from show business and then I ended up imitating it, then I ended up being it.

MS: But you did so from the more performative aspect of theatre. Pulling back that curtain, throwing it on a heap on the ground and setting it on fire. I came from a place of – I’m an old hippy – opening up my heart in sincerity and putting it into the music and into my performances. It was a different perspective from a music lover’s perspective or an artist’s perspective. You end up in the same place, having come from very different directions.

CS: Yeah, it sounds like you started from the inside out and I started from the outside in.

How did it feel to be in such close proximity with someone you’ve been friends with for so long. Is it hard to work from a position of objectivity?

CS: Michael is vicious. [laughs]

MS: You’re so courageous. The song Walk Unafraid is about stepping into fear rather than running away from it. Patti Smith offered that advice. She told me, ‘You need to walk unafraid’. I was like ‘Whoa, can I have that?’ and she said ‘Yeah, take it’. You and Patti are the most unafraid people I’ve ever met. In the studio, one of the most vulnerable places that I can ever artistically or creatively place myself, you’re completely unafraid. It’s mind-blowing to me how you allow your vulnerability to become part of your process. And you have no ego; if certain things that I said to you or suggested had been said to me, I would have crumbled. You’re so strong. We learnt a lot, working together. But we’re a family – I love Casey until the end of time and he knows that, so I think that it allowed for this atmosphere in the workplace where we can be completely honest with each other, not only in work but supporting each other in difficult times. We had no problem stepping away from the studio and going for lunch every single day, or going out and experiencing a bit of theatre or a live show of some kind, having drinks and just being friends again – and then we’d be back in the studio the next day.

It sounds like as much as it was a working relationship, it was quite an important personal one for you both.

CS: We did a lot of writing at Michael’s home in Georgia. My personal life was in such a state of decay and despair that it was incredible to be able to leave and go somewhere safe. I felt safe and taken care of there. When I’d get to Athens, I would just unfurl in a way that was just incredible. It was also very intense. We spent all of our time together – we lived together, worked together. Sometimes there was delirium because we weren’t sleeping much and Michael has a very stoic diet at times. I would be crying, eating gruel. You’d have like miso paste and brown rice and I’d be going out to eat a cheeseburger and go to the nightclub. I call it a celebrity-writing-retreat-spa.

MS: Athens vibrates on a completely different frequency to New York. As anyone who lives in New York for any period of time will tell you, you have to get out of the city from time to time. You go crazy if you don’t.

How does it feel to be able to release such an intensely emotional record, in such wildly different musical landscape?

CS: I love it. I don’t think we’ve ever charted in Japan in the first week of release. I don’t know what the shift is, but maybe it’s because we’re connected to a more global audience for the first time in our history. I’ve always wanted to go to Japan and I had such a love of Japanese culture.

MS: I might have to jump on the plane if you book some shows in Japan.

CS: Yeah, you do!

MS: If you go to Japan, I’ll come too. I'll find some Japanese gruel and miso paste for you. How about that?

Fischerspooner’s new album, Sir, is out now.