The Indie Scene Set to Dominate Music in 2018

- TextTom Connick

Meet the bands, artists, and behind-the-scenes cogs of one of the most exciting musical revolutions in years

LIKE ALL GREAT British stories, it starts with a pub. Tucked away off the bustle of Brixton high street, The Queens Head was a South London boozer in the purest sense – a shabby hub of local community and late-night excess, which attracted the beatniks and vagabonds of the area like moths to a flame. With no set opening or closing times, and an ‘anything goes’ attitude to debauchery and illicit substances, it was a home from home for firebrand punks and one-time NME darlings Fat White Family, whose flame first struck on the Queens’ diminutive stage. The Queens fast became a legendary spot in modern British indie lore; tucked away in its cramped upstairs practise space, Shame began writing its future.

Figureheads of an emerging scene of young, exciting new London bands, Shame are leading the likes of HMLTD, Sorry, Goat Girl, YOWL and more into a new era for British indie – one free of jack-the-lad post-Britpoppers and overly-polished pretenders; one which thrives on its grit and bile. Musically disparate, but socially and culturally united, it’s a scene in its purest form – one born out of friendship, favours and mutual artistic respect.

Shame were loaned that practise room for free by The Queens’ landlord, a longtime friend of drummer Charlie Forbes’ dad. The Forbes family had been regulars at the pub since Charlie was a young boy, the drummer sharing a seemingly bottomless well of tales of jacked-up locals, Christmas dinners in the pub kitchen, and twisted parties that would go on for days on end. Popping to The Queens after school soon became routine for Forbes and his newfound bandmates – singer Charlie Steen, bassist Josh Finerty, and guitarists Eddie Green and Sean Coyle-Smith – as they channelled their adolescent rage into gravelly post-punk tales of self-deprecation and sarcasm, like the unmissable One Rizla. A de facto after school club, the five-piece’s youth aided them in avoiding the more grisly recreational activities that were occasionally on offer at The Queens. “It was the right age for us to be there,” nods Forbes, in a welcomed break from signing vinyl copies of the band’s debut album, Songs Of Praise.

The same week Songs Of Praise is let loose on the world, and the same week we meet Shame, the BBC reveals its ‘Sound Of 2018’ picks for musical stardom and success. Pushing the squeaky clean pop stars of the future, while the London scene celebrates its grimy brothers’ coronation with sweaty mosh-pits and spilled pints galore, it’s a contrast that’s impossible to ignore – running parallel to the superstars of tomorrow’s first big nod from the industry behemoth, there’s a party going on in a new musical scene far more in keeping with the reality of British youth, born out of a free-spirited, drug-fuelled South London den. It’s enough make most major label execs shiver. “We weren’t ‘on it’ all the time,” a smiling Steen assures us of those days in The Queens, while Coyle-Smith offers a glint of positivity as the ‘elephant in the room’ conversation of the pub’s druggy reputation threatens to veer this wholesome tale off-road: “I think they quite liked having us there – we were like, the hope!” he says to peels of laughter, “None of us got into the crack or heroin side of things... So that’s good!”

While they might have made for some... unconventional peers, the clientele of The Queens Head soon filled a void where Shame’s school friends began to fall by the wayside. “It was that period where everyone [at school] started to go clubbing, at XOYO or wherever,” says Coyle-Smith, “and personally all of us were really not into that at all. We more like the ‘hanging out in the garden of a pub’ thing.” Popping their head out the window of that cooped-up rehearsal room, they’d find themselves heading downstairs for pints at every opportunity, catching up with the oddballs that passed through the pub, before heading back upstairs to put their madcaps tales to tape. “There was always something going on in that pub,” says Steen, misty-eyed. Coyle-Smith agrees: “We didn’t really realise the significance, at the time, of how much influence it was having on the music, just being in that environment.”

Songs of Praise is a patchwork encapsulation of oh-so-British malaise, usually confined to pub chat in local hubs just like The Queens Head. Stories of creepy men preying on young girls nestle up to more meandering numbers like The Lick, a spoken-word anthem for a disenchanted youth just searching for something “relatable, not debatable”. Friction speaks of political frustration, while Concrete comes off like a fidgety, back-and-forth argument between a young couple. It’s a combination of gruff, world-weary post-punk and personal struggle, thrashed out by the band as Steen bawls atop the melee, himself sounding several pints deep and clamouring for a scrap. It’s also one of the strongest British debuts in years.

If Songs Of Praise is a document of the characters and calamity of The Queens Head, it also acts as something of a eulogy –in 2015 the pub was boarded up and bought out, leaving this community without its epicentre. Unsurprisingly, it reopened some months later as a squeaky clean craft beer bar, with its eclectic former clientele priced out and sent packing. “We had a bit of time where we were like, ‘Oh… what do we do now?’,” admits Green, Shame’s youthful naivety meaning they never once questioned the fact they’d not had to pay a penny in rehearsal room rental. (“People cared about Shame and obviously saw something,” says Forbes by way of explanation, before Coyle-Smith smirks: “Something we didn’t!”) Luckily, another friend of The Queens offered them free space in neighbouring Camberwell’s Dropout Studios, but there was still a gaping hole in their lives. “After The Queens had gone, we just naturally wanted to recreate something like that, putting on our own nights, all your mates being there, the same people coming down...” says Coyle-Smith – “That sense of community,” adds Steen, finishing his bandmate’s sentence.

***

ENTER THE DELIGHTFULLY-NAMED Chimney Shitters – Shame’s promoting moniker, under which they began using the sweat-soaked, stinky stage of Brixton venue The Windmill to showcase their friends’ bands and foster their own sense of community. Sorry were one of the earliest enlistees, though the North London-based they were scared off the bill of their first booking by a friend who warned them they “weren’t good enough” to rival Shame’s swiftly rising stature. After that “everyone just became friends through those gigs,” says Sorry singer Asha Lorenz, praising The Windmill for always pulling “the same people” and fostering a community in the Southern reaches of the capital – so much so that they’re frequently dragged all the way down there for pints and parties. It’s a far cry from their childhoods – too young to enjoy the early 00s Camden indie goldrush that saw The Libertines and Amy Winehouse stumbling around North London for nights on end, Lorenz had no interest in the gigging scene “until I was about sixteen – we couldn’t get in anywhere!” she smiles. “The Nambucca thing,” she says, referencing the legendary Holloway Road venue that dominated NME headlines at the turn of the century, “we just missed that wave.”

When we speak, Lorenz and her fellow guitarist Louis O’Bryen are still nursing two-day hangovers after Shame’s surprise release party at The Windmill – O’Bryen’s even carrying a mystery graze on his chin, which he’s soon reminded came as part of a ill-informed bet that he could scale the wall of its smoking area. It’s clear that despite their North London upbringing, the Brixton venue’s still integral to their collective identity, bloodied chins and all. “There are other venues that people play or go to, but I’d say that’s the Mecca,” agrees Goat Girl’s Rosy Bones, herself a regular of its hallowed walls. “The Windmill seems to attract friendly, like-minded people and one thing leads to another, and so on, and so on.”

The Windmill fast became the go-to spot for those with their ear to the ground, a myriad of young creatives flocking to it to share their wares and drink in those of others. Its eclecticism is its strength – while Shame might be casting out their barbed post-punk, Sorry could open proceedings with their twisted, mutating art-rock, not unlike Wolf Alice after two tabs of acid. Goat Girl are an altogether more menacing proposition, and YOWL shine the frenetic, taut energy of Parquet Courts through a lens of modern British anxiety, while notable audible outlier (but friendly face to everyone) Matt Maltese channels a more classic singer-songwriter vibe – Leonard Cohen and Nick Cave are common touchpoints for his piano-led, self-proclaimed “Brexit pop”. All of them found refuge in The Windmill.

“The current situation that young people in the UK are faced with is fucking bleak – there has to be a reaction” – Charlie Williams

“I think it was just good nights out,” says Coyle-Smith when pressed for The Windmill’s wide-reaching appeal. “There’s so many photographers, and people who make films, and t-shirts, and posters…” Finerty agrees: “The people who go out to the Windmill are pretty creative people anyway.”

“There’s always people you recognise, which is nice to have in a place like London,” says Maltese, “It’s super rare.” Nodding to Dalston’s Shacklewell Arms as another “home from home”, YOWL guitarist Ivor Manley agrees: “They’re like local pubs in a massive city.” His brother, bassist Jake Manley praises The Windmill’s attitude: “They just seem to not give a fuck, as well – they put on whoever, and it’s a good mixing bowl of fuckin’ everything.”

Though all of The Windmill’s regular patrons tread their own path, Maltese is perhaps the best example of that ‘mixing bowl’ mentality. His grand songwriting talents seem best suited to mainstream recognition, but his early days were as skittish as the rest of his peers’. A few dodgy gigs around his hometown of Reading pushed him towards the capital, where he discovered Sorry, sparking a fast friendship. Though he could surely shoot for more shiny, arena dates in the coming months, 21-year-old Maltese seems quite content where he is for now. “It definitely makes it nicer to gig,” he smiles, “when you’re with people you like.”

“Everyone kind of keeps an eye out for each other,” says YOWL frontman Gabriel Byrde, both his arms clad in plaster casts after a nasty bike accident – clearly, that protection racket doesn’t cover self-inflicted injuries.

It does, however, extend to their shows. Just a few hours after we speak, YOWL play a packed-out set at Shoreditch’s The Old Blue Last – broken arms and all. Snarling, spitting and hurling himself into the crowd, you’d never have guessed Byrde was nursing two fractured limbs. With spirits high, the night ends on a sour note and some confusion, after heavy-handed bouncers grapple with, and ultimately eject Hotel Lux frontman Lewis Duffin. Within hours, Shame are online, calling for a boycott of the venue. “Just heard that our dear friend Lewis had been choked trying to go backstage at the venue his band were playing at so yeah, fuck The Old Blue Last,” they tweet. That united spirit still stands, even outside of The Windmill’s walls.

AS RECORD LABEL A&Rs and buzz-devoted blogs alike soon caught wind of The ‘mill’s special charm, Charlie Williams of Golden Arm Management was granted a sneak peek at its future. After catching the now sadly defunct Dead Pretties play “the most ramshackle and brilliant set I had seen for years”, he knew something was brewing. “Going back to The Windmill felt like a secret club that everyone was invited to – being a part of it felt necessary,” Williams says.

The business head of this barmy bunch, Williams praises Sorry bassist and longtime London gig promoter Campbell Baum, and The Windmill’s in-house booker Tim Perry, for being “forces in booking and grouping together the most important bands of this generation.” He soon swept into the fold, releasing records from Sorry, Dead Pretties, LICE and more on his own label Wintermute Tapes, and offering them an industry leg-up with none of the compromises typically associated with such moves, bringing The Windmill’s many regulars into Golden Arm. He’s far from a pencil-pusher, though – “I’ve spent many nights in The Windmill, holding speaker podiums for dear life to keep crazed audiences from completely knocking out the sound,” he confesses.

“I believe completely that there always has to be a “hang the DJ” moment in any wave of inspired music,” Williams explains, referencing The Smiths’ track Panic and its lashing out at a once-tired musical era. “Once you have the current situation that young people in London and the UK as a whole are faced with – which, to be honest, is fucking bleak – there has to be a reaction. The most exciting aspect of this for me is that, whereas with other musical movements there has been a uniting sonic factor, all of these bands have their own unique sounds whilst sounding like they exist in the same world.”

***

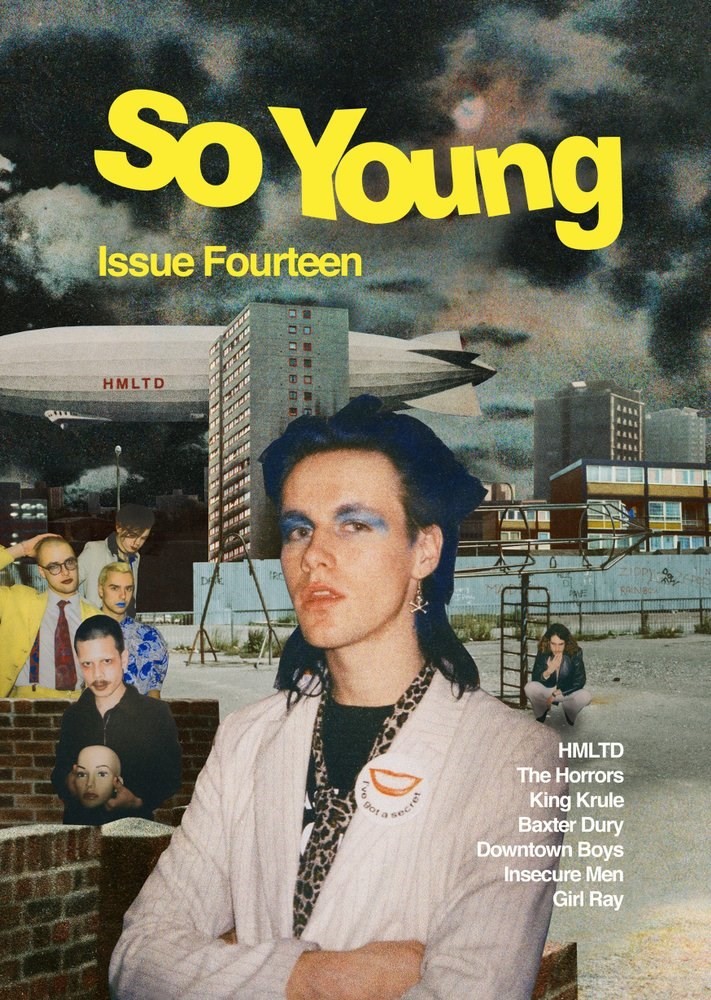

“It’s sort of a ‘hallelujah moment’ for indie bands” – So Young magazine

IF THE WINDMILL is that world’s new place of worship, So Young magazine is its holy scripture. Initially started back in 2013 as a means to pay homage to the Xerox fanzines of the 70s, its collage-esque aesthetic and irreverent style came into its own once this London scene began entering its field of vision. “I think the most exciting thing for us, especially with the first crop, is that we found each band individually for their qualities as their own band,” explain co-founders Sam Ford and Josh Whettingsteel, over email. “We didn’t stumble upon a collective, we just heard from or heard of three or four bands across a short period of time. The first being Shame who we tried to book for a show about three years ago, but they all had their college exams and couldn’t play. From there we heard rumours of Goat Girl. Collectively they’re a huge talent, and the intensity of [vocalist] Lottie just sealed it for us. Dead Pretties reignited our belief that ‘punk bands’ weren’t dead when they played for us at The Old Blue Last, supporting The Lemon Twigs and Yak.”

It’s Sorry who seem to really ignite So Young’s passion for the world they’re swiftly becoming the go-to reportage of, though: “They receive a lot of deserved praise for their songwriting, but for me I think it’s the relationships in that band that draw me in the most,” the pair continue. “They’re a true collective, and possibly the glue within the whole scene. So from finding these bands individually, we then realise they’re from the same place – or at least playing the same places – and the whole thing becomes a scene... a sort of ‘hallelujah moment’ for indie bands.”

So Young’s aesthetic perfectly apes that of this emergent bunch of music-mad youths – scrappy and pieced-together from a multitude of elements, that collage style is the ideal fit for the rough-edged, disparate sounds it documents. Alongside go-to poster and record artwork creators Spit Tease, and photographer Holly Whitaker of the FLOP Collective, they’re lifting the scene out of the speakers and crafting its visceral visual side.

“A lot of it started because we didn’t know how to use Photoshop,” laughs Spit Tease’s Flo Webb, who heads up the hands-on collage works alongside childhood friend Mac Westwood. “Having to hand-make everything, even down to cutting out tour dates and sticking them down, it was purely because we had no other way to do it!”

“It’s quite therapeutic, as well,” admits Westwood, “because it takes ages.” From their first commission to produce Sorry’s first t-shirt, through to tour posters for Shame, fully handmade zines, and eventually record sleeves and merchandise for almost every band in the scene, Spit Tease’s eye for slightly macabre art has given an collective identity to their friends’ musical escapades. They held an exhibition alongside Sorry’s recent single release show at Corsica Studios in December, further evidence of the collaborative creative spirit behind these old school friends’ latest movements, and the desire to showcase something “more than just a gig”, as O’Bryen puts it.

***

THAT FEELING OF creating something ‘more’ is core to this exciting new breed. What they might lack in shared musical identity – though, notably, they all harbour a discomforting edge to their various sounds – every band in the scene speaks of a desire to push boundaries.

Fittingly, it’s Shame who are leading the charge. With tour dates in Australia set to bring their millennial malaise to sunnier climes, they’re itching to escape the grey road network of Europe, which has thus far informed their bleak outlook. Sorry, meanwhile, are readying releases to drop on their new label home Domino, which they share with big hitters like Arctic Monkeys, of all bands. Matt Maltese’s debut album is imminent on major player Atlantic Records, with another already pencilled in for “exactly a year after the first.”

Most intriguingly, though, Shame’s Coyle-Smith speaks of “a second wave” that are already snapping at their heels. From new arts promoters like Femme Collective and TUSK, to bands like Black Midi, Sistertalk, Drug Store Romeos, Crewel Intentions, LICE, Hotel Lux and many, many more, there’s already a future to this fertile new breeding ground of musical misfits – one which is inspiring groups based far outside of The Windmill’s South London catchment area.

It’s business-minded Charlie Williams who best sums up both the limitless ambitions and the hometown sentimentality of his ragtag bunch, as they hurtle towards the fame and infamy 2018 is destined to bring them: “From the Windmill to the world, right?”