The Designer Challenging Archetypes Of Black Masculinity

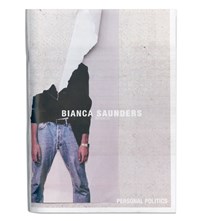

Meet Bianca Saunders, the RCA graduate exploring race and identity – here, we tell her story and preview her research zine titled ‘Personal Politics’

Menswear designer Bianca Saunders is explaining to me why identity features so heavily in her work. “White people are seen as standard. They can be whoever they want and be influenced by whoever they want,” she says. “But my blackness removes me from that.”

Saunders is one of the few black British women taking on men’s fashion. Her contemporaries, in as much as they exist, can be counted on a few fingers: Grace Wales Bonner and Martine Rose are perhaps the only other people doing so – though, it’s important to note, their collections are continually among the most celebrated at London Men’s Fashion Week.

A fresh-faced master’s graduate from the prestigious Royal College of Art, where she studied Menswear Design, Saunders’ work is deeply thought-out and artistic, although she would hesitate to describe herself as an artist. But slowly, she’s moving in the direction where that label will be unavoidable, even if it’s one she doesn’t feel comfortable staking.

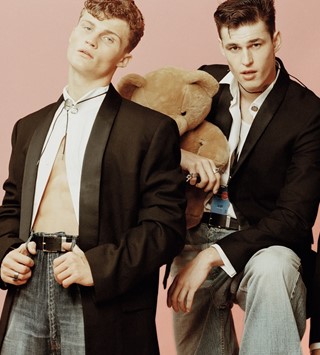

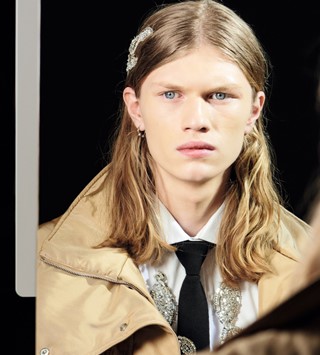

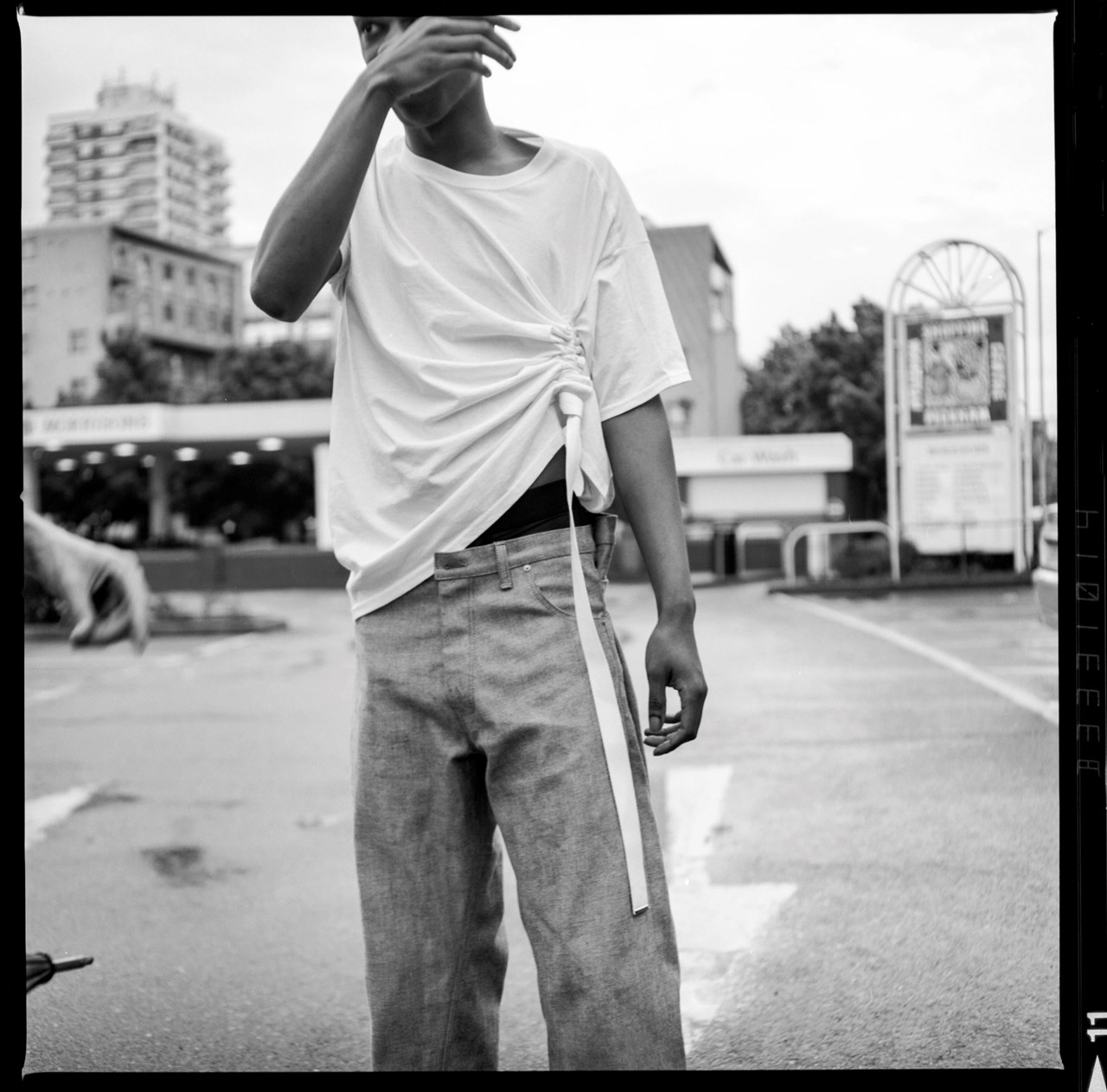

Saunder’s second collection, Personal Politics, is a grand undertaking – elevating simpler styles with thick pinches of fabric, or rucksack-like straps which stretch over the body. They’re versatile; a sheer, asymmetric top can be worn cropped or not, while trousers are sexualised with long, suggestive zips which can be revealed to show thigh. A standout piece is a pair of perfectly gold vinyl slacks – to me evoking a new romantic aesthetic with a hint of street-wise grunge.

To accompany her collection, Saunders is launching a Personal Politics research zine – a sweet flick-through previewed here, which features poetry by some of London’s up-and-coming spoken word artists and writers such Seye Isikalu, Abondance Matanda, Caleb Femi and James Massiah. The zine is filled with scrawls and commentary on black masculinity and sexuality, which make up some of the core ideas behind the collection. “Oh batty boy jeans / like these I wear / I’m straight as a string / caucasion (sic) hair / no kink in me / I’m blackest black / no, blacks aren’t gay,” reads an excerpt of a poem by Massiah.

“White people are seen as standard. They can be whoever they want and be influenced by whoever they want,” she says. “But my blackness removes me from that” – Bianca Saunders

Both at Kingston University, where she did her undergraduate degree, and at the RCA, Saunders was the only black woman in any of her classes. “It was literally like ‘spot the black person’,” she laughs. As a visible minority in a structured environment, she couldn’t help thinking about her identity in depth, especially when she had to put up with a myriad of ignorant questions. “Sometimes you just want to sit out of these conversations. You have to defend a whole community. I remember speaking about how my work is about where I’m from and identities that mainly involve black people, and my tutor asked me, ‘Why do you need to do that?’ I just started crying.”

Saunders grew up in south London, moving around a lot after her parents – who are both of Jamaican heritage but born and bred south Londoners – got divorced. “We lost a lot of stuff, so I don’t have a lot of baby pictures of myself. We lost a lot of money too, I guess,” she says. Saunders wasn’t particularly academic, and nor did she grow up on a diet of Vogue, or any of the other high-fashion magazines. “I’d buy Look Magazine and be like, ‘I wanna wear that!’ Fashion for me is less about style and more about the process of combining different ideas.” Her icons don’t all live in the fashion world either; she cites Kelis, Solange and Cardi B – “people who are themselves” – as figures who inspire her.

While she doesn’t come from an artistic background, Saunders’ large family is the backbone of her work. She’s one of six children, and over 30 grandchildren. Her mum, a hairdresser, is very supportive of her designing but gets frustrated with the hours she has to work. “I’ll come home at 11pm and she’ll be like, ‘Where have you been?’” she says. Her dad, a plasterer, sometimes asks, “Are you going to get a job?” though he did compliment her website. Her world, like so many children in the creative industries from working-class backgrounds, is just removed from her parents’ experiences.

Her interest in black masculinity partially comes from observing him and her male siblings and cousins – the way they interact. She worries about her brother and thinks that "if you’re a guy it’s easier to get involved” with negative things.

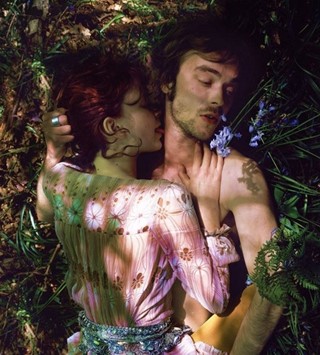

Above all, Saunders feels like black masculinity “should be a choice”. Unlike artists like Robert Mapplethorpe, whose explicit photography sexually objectifies and fetishises the black male body, she wanted to look at the men who were actually around her. Much like her contemporaries, photographer Campbell Addy and stylist Ib Kamara, she’s become more interested in the fragile and gently flamboyant side of black men’s psyche, rather than the way they’re perceived outwardly as being, say, aggressive.

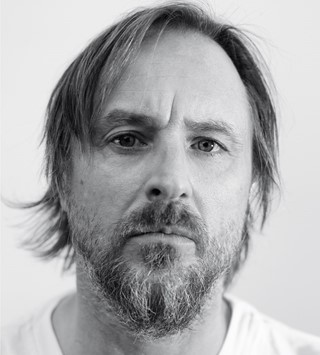

If you follow Saunders on social media, you’ll see that she’s always celebrating others. “I can’t help it. It’s how my mum is,” she explains. The friendships she’s cultivated because of this mean that she’s collaborated with some amazing people since being drawn into the menswear world while studying at Kingston (initially she was studying womenswear). The zine is a case in point, but she’s also been informally mentored by sculptor Thomas J Price, a fellow RCA alumnus, and recently worked with Akinola Davies Jr on a Nowness film titled Permission, which features her Personal Politics collection.

“It’s in relation to things like Black Lives Matter, the politics that have been going on have meant we are growing into new people. We’re seeing how our parents’ generation handled things and we’re restructuring them…” – Bianca Saunders

Adama Jalloh, a talented south London photographer, shot her collection, and writer and model Kareem Reid has functioned somewhat as a muse thanks to his unabashedly open, gracious style and articulation of black masculinity. In her end of year RCA show Kareem was lifted over the heads of his fellow models, prone and bathed in pink light – a subversion of the trope that often sees black men dressed in “millennial pink” to make a basic statement about how they aren’t allowed to explore their femininity. The mantra is “You don’t have to wear pink, or crop tops, to show that you’re a carefree black guy,” but also that you can if you want to.

But why now? “It’s in relation to things like Black Lives Matter, the politics that have been going on have meant we are growing into new people. We’re seeing how our parents’ generation handled things and we’re restructuring them… We’ve seen black boy joy on social media, Frank Ocean created a new image of what it is to be black and queer and he’s created a space for his masculinity to sit in queer culture. There’s just more images,” Saunders explains. The title, Personal Politics, starts to make sense.

I ask her if there is something special about being one of the few black, female menswear designers working in Britain. There’s a long pause. “Yeah, there is. Around December-time I would have said it was a lot of pressure because after my first collection people were asking me what I was doing next… It’s so frustrating, there’s so many talented people. Me even being at the RCA, I would hope that it inspires more black people to apply.”