Maksim Finogeev’s archive-based photo project, Snapkins, wonders why it’s so taboo to talk about those who don’t achieve their dreams

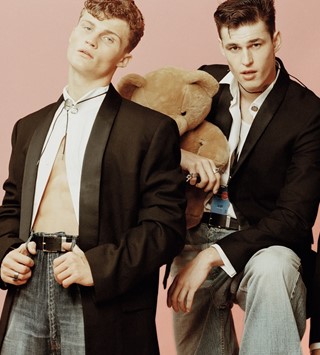

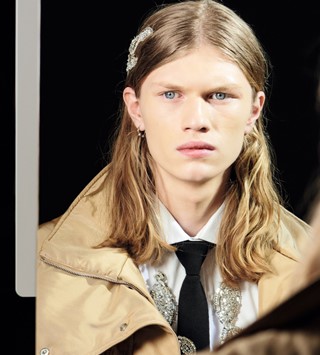

Mere years ago, before Instagram held total sway over the fashion industry, aspiring models in the post-Soviet territories were uploading their snaps to a page on VKontakte (the Russian-language equivalent to Facebook) called ‘Typical Man’s Modelling’ and receiving instant feedback to the question: “do I have any potential for a career in modelling?” The 50,000 member-strong group, made up of casting agents, photographers, fellow models and assorted gawkers would invite any guy to drop trou, stand before a neutral backdrop and upload unretouched snaps of themselves. They’d then receive an oft-brutal barrage of online vitriol about their physical attributes.

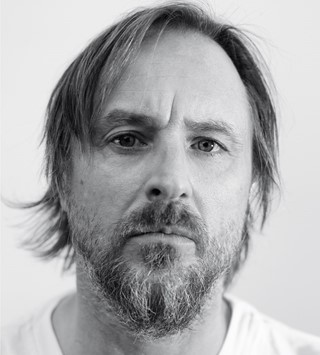

From the moment he discovered the group, Ukrainian artist and fashion photographer Maksim Finogeev found its inner workings deeply problematic. At the time, he was scouring for fresh faces on VK, and was disappointed that the group assesses guys based on what he calls the Brad Pitt criteria. “The group is supposed to be about making recommendations, but it felt more like members making a final decision on the guys’ behalf, and according to very commercial criteria,” he tells Another Man. “This is a fragile fashion community who reject requests made by many to join their tribe.”

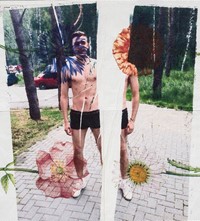

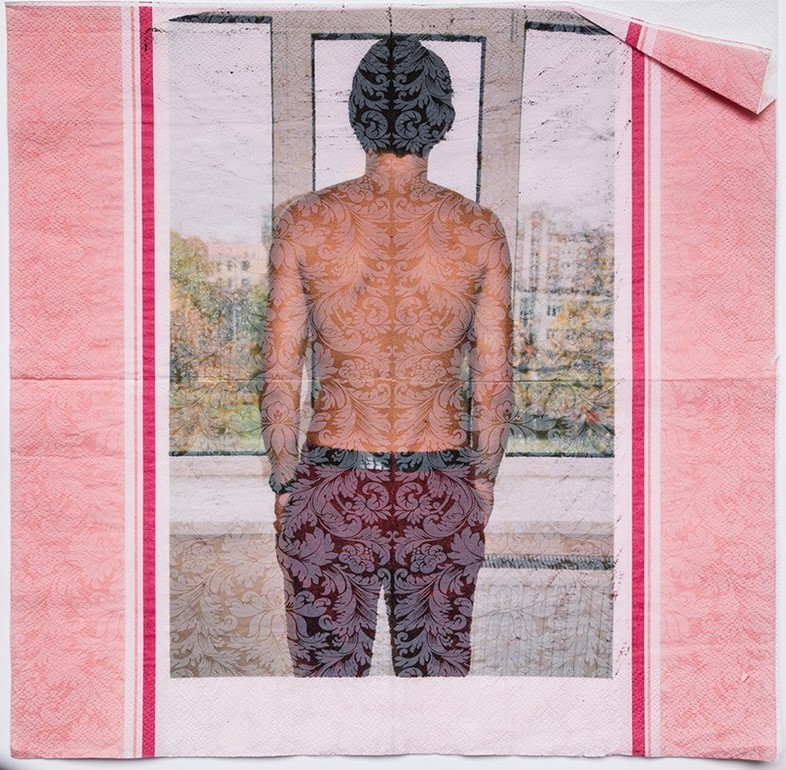

Wondering how all these young men had digested their brutal dismissals, Finogeev developed a project based on the snaps they had submitted, which he printed on discount napkins with childlike motifs of cute animals, burgers and toy cars to evoke the fragility and naivety of their dreams. “I chose napkins to suggest the vulnerability required to share your desires and your looks, especially in such a huge industry like fashion,” he explains. “Some people don’t quite understand the scale of it. You’re not only going up against the world of beauty, but also the world of capitalism and consumerism.”

The series, entitled Snapkins, is on view as part of the Circulation(s) Festival in Paris until June 30. On site, each snapkin is framed, accompanied by the poster’s first name and measurements, with the artworks mounted at different heights on a wall – a powerful reminder they’re staring at real people. “Visitors can compare their height with that of each model,” explains the 31-year-old artist. “I wanted to evoke the notion of casting – in some ways, I’m asking you to participate in the appraisal process. Do you think these are good candidates for modelling?”

On the surface, Snapkins is about a consumer culture that regards the bodies of these fame-chasing youths as disposable products. But Finogeev also questions why much of our culture regards as taboo the plight of those forced to reconsider their lofty dreams. “Few people want to talk about these kinds of experiences because it’s very difficult to realise that you won’t achieve what you set out to do,” explains Finogeev, who also co-organises Odessa Photo Days, the only festival in Ukraine dedicated to contemporary photography. “Readjusting one’s expectations is not easily done. For example, shifting your ambition from being a model to a sales manager.”

As a photographer, Finogeev prefers to create images by repurposing and recycling existing materials, as he reckons “there are already too many images out there”. In that respect, Snapkins fits right in with the Circulation(s) Festival’s broader theme of innovations in archival material (“the posthumous destiny of images”). “Everyone is talking about the pollution of industries and cars, but not about the impact of photo production,” asks Finogeev, who describes Snapkins as both an eco statement against art-world overproduction and a critique of the fashion world’s cruel capitalist raison d’être. “What is the ecological cost of creating so many images?”

As for the emotional toll such a public rejection process takes on these Snapskins guys, Finogeev enjoys not knowing whether they kept chasing their dream or promptly gave it all up. “For me, it was important not to know their reactions following all the negative comments they were subjected to. I leave it an open-ended question: did they figure out from this experience that they weren’t models, and abandoned this dream? Or did they persevere and try to find another way to break in? Your guess is as good as mine.”

Maksim Finogeev’s Snapkins series is on view as part of the Circulation(s) Festival in Paris until June 30, 2019.