Clare Waight Keller on the Angelic Gay Icon That Inspired Givenchy S/S19

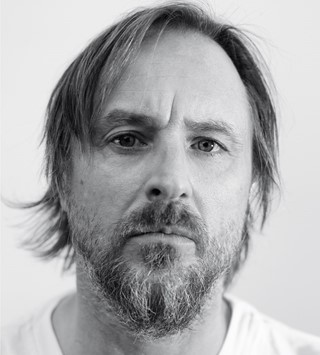

- TextTed Stansfield

From 1930s authors, photographers and diplomats to, most recently, Givenchy’s artistic director Clare Waight Keller, Annemarie Schwarzenbach’s androgynous style and audacious spirit has entranced through the ages

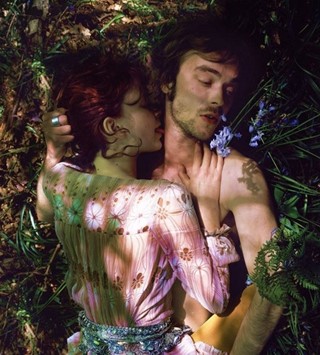

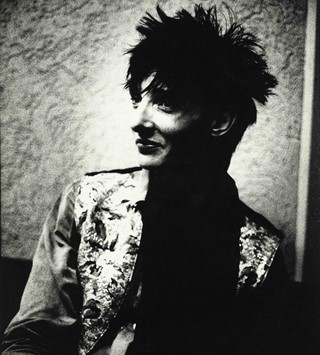

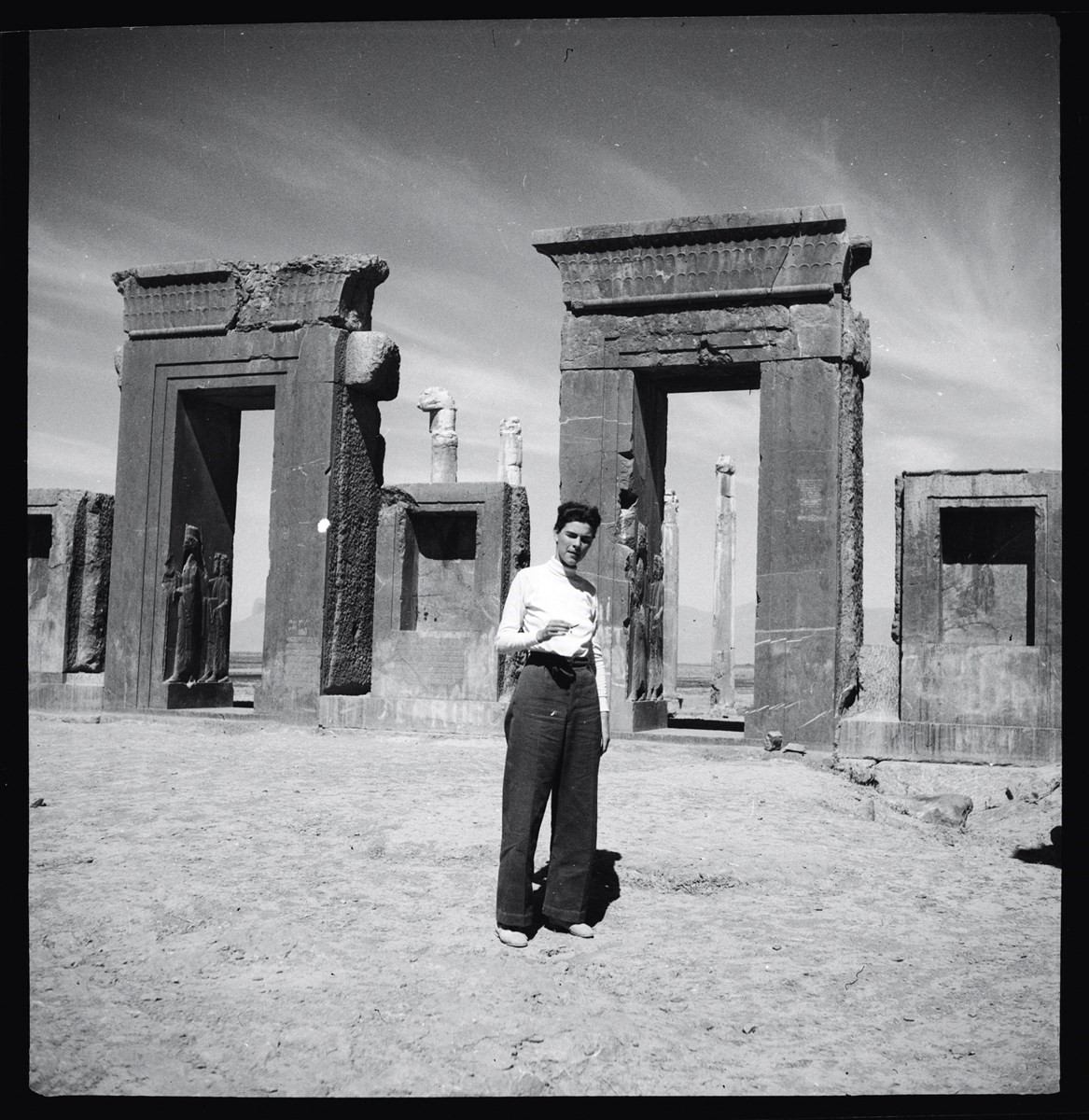

When American novelist Carson McCullers met Swiss author and photographer Annemarie Schwarzenbach in the summer of 1940, she fell in love – instantly and hard. “She had a face that I knew would haunt me for the rest of my life,” she said. McCullers wasn’t the only one to become enraptured with Schwarzenbach: German novelist Thomas Mann called her a “ravaged angel”; another writer, Roger Martin du Gard, said she had “the face of an inconsolable angel”; while German photographer Marianne Breslauer, who took numerous photos of Schwarzenbach, likened her to “the Archangel Gabriel standing before Heaven”.

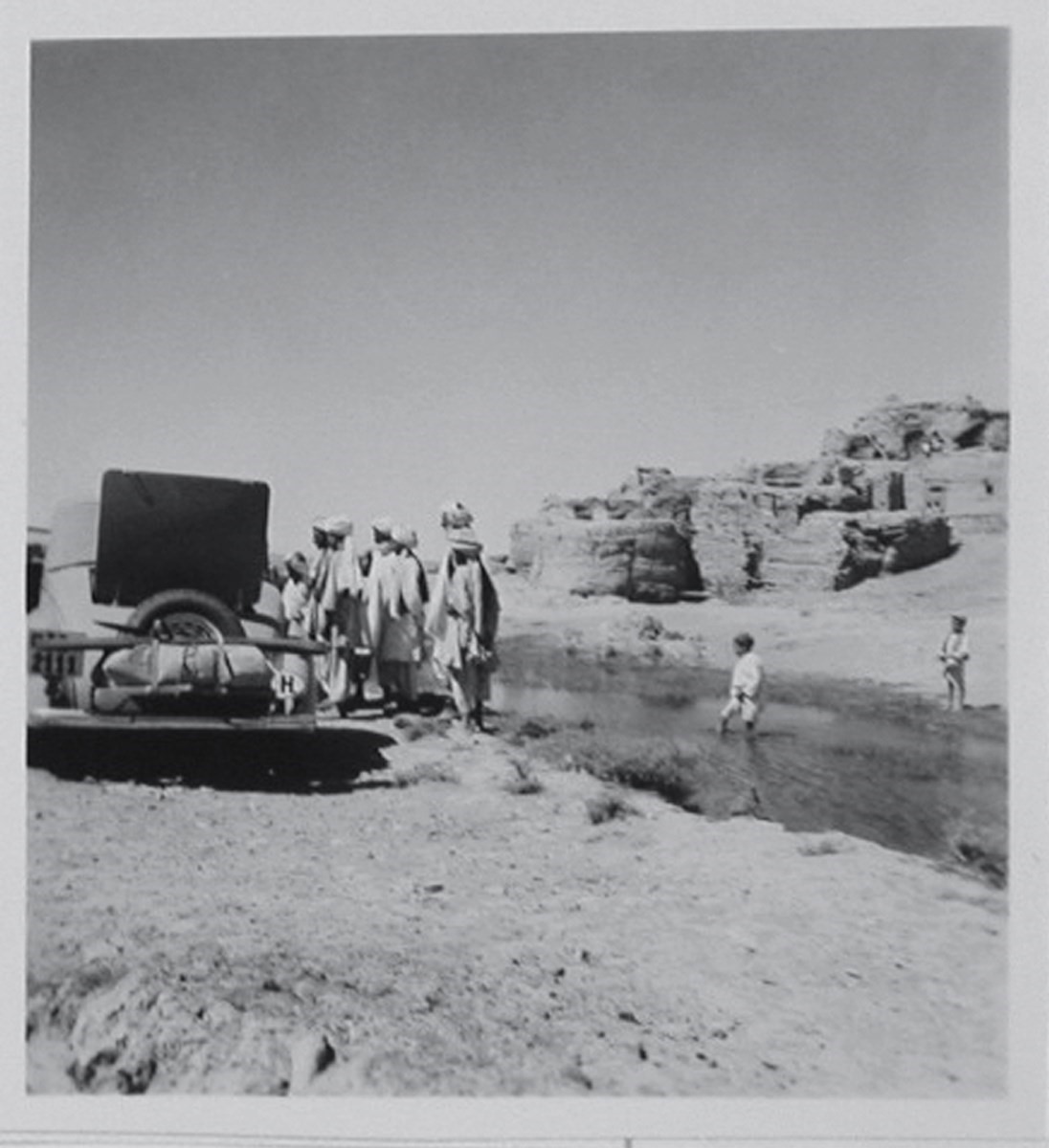

But with the rediscovery in the late 1980s of Schwarzenbach’s body of work – a rich catalogue of journalism and photographs documenting her adventurous farflung travels – she gained new interest for more than just her angelic beauty; she was recognised as a female pioneer and a gay icon. In 2001, there was even a feature film, The Journey to Kafiristan, tracing her 4,000-mile drive from Geneva to Kabul in a Ford Deluxe with ethnologist Ella Maillart (‘How far would you go for true love?’ read the tagline).

Born in Zurich on 23rd May 1908, into a wealthy family, Schwarzenbach was always a nonconformist. Her bisexual mother Renée, the daughter of a Swiss general and descendant of the Bismarck family, dressed little Annemarie in boys’ clothes from an early age. She wore men’s clothes for the rest of her life, and was often mistaken for a man, favouring tailored suits, fitted sweaters and collared shirts – a wardrobe that both reflected her conservative background and the bohemian lifestyle she later pursued. She had a taste for haute couture too; while in the throes of a passionate affair with the daughter of the ambassador of Turkey to Persia, she would steal and wear her lover’s gowns.

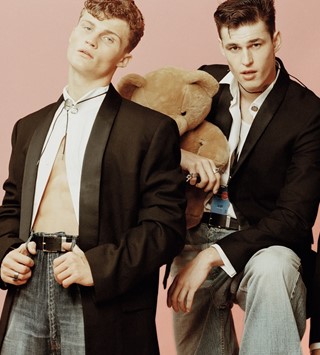

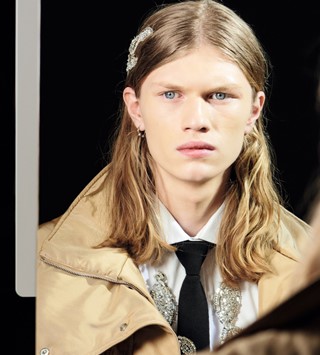

This year, Schwarzenbach’s incredible style informed Givenchy’s Spring/Summer 2019 collection. The house’s artistic director, Clare Waight Keller, directly referenced images of the “hauntingly handsome writer”, presenting tuxedo jackets, leather motorcycle jackets tucked into army trousers, and elegant gowns that reflected the bias-cut 1930s fashion – and perhaps those stolen frocks. “I was researching silhouettes, and came across this spectacular looking woman, Annemarie Schwarzenbach, who dressed sometimes as a man and sometimes as a woman but always in a modest, elegant way,” explains Waight Keller. “It spoke to me, as it aligns perfectly with what we’re doing at Givenchy. I find the idea of not being defined by a gender in the way you express yourself through clothes extremely modern. Her sense of freedom in the way she would present herself as a different character from one day to the next is highly inspiring. I also love the message about acceptance and tolerance her story gives: she was at peace with her androgyny, and so many years later, it still inspires people like me to keep on colliding codes.”

Schwarzenbach’s legacy goes beyond fashion. A talented writer, she published her first book in 1931 when she was just 23 and, after a brief stint in Berlin where she enjoyed the last hurrah of the Weimar Republic (according to her friend Ruth Landshoff, “she lived dangerously. She drank too much. She never went to sleep before dawn”), she embarked on a career as a photojournalist. Producing 365 articles and 50 photo-reports for major Swiss, German and American newspapers and magazines in the space of just nine years, she travelled to Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Iraq and Persia, and later Afghanistan, the USA, the Baltic states and Russia, often unaccompanied.

Her personal life was no less frenetic. A committed anti-fascist, she helped her friend Klaus Mann, son of Thomas Mann, finance the literary review Die Sammlung, which published exiled German writers; and she used her diplomatic passport – a by-product of her marriage-of-convenience to the gay French ambassador to Persia, Claude Clarac – to rescue anti-fascists in Austria. But her political commitment resulted in unbearable tensions with her Nazi-sympathising family, culminating in 1934 with her first suicide attempt.

And then there was the matter of her morphine addiction. A user from her early 20s, Schwarzenbach spent much of her life struggling to kick the habit. In fact, that audacious car journey to Afghanistan in 1940 was another failed attempt to clean up; her co-traveller Maillart chronicled the difficult experience in the book All the Roads Are Open: The Afghan Journey. That same year, the Manns introduced Schwarzenbach to smitten novelist Carson McCullers. Seventy years later, Suzanne Vega wrote the song Lover, Beloved about McCullers’ unrequited passion: “Everyone wants you, everyone loves you, how can I possibly compete?”

The mounting stress of this doomed affair and the death of Schwarzenbach’s father led to a second suicide bid, this time in New York. She was promptly admitted to a psychiatric ward, diagnosed with schizophrenia and subjected to weeks of barbaric treatment. Schwarzenbach escaped, was hospitalised again and then forced out of the US, winding her way back to Switzerland via Portugal, the Belgian Congo and Morocco. Tragically, once home she suffered a serious head injury from a bicycle accident that resulted in more hospital and more morphine. Her mother Renée refused to allow visitors – even her estranged husband Claude was turned away. Two months later, Schwarzenbach passed away, aged 34.

In a final twisted act, Renée destroyed most of her daughter’s diaries and letters, believing they shamed the family. Thankfully, one of Schwarzenbach’s friends held on to a collection of photographs and writings, and in the process saved Annemarie Schwarzenbach from the mists of obscurity.

This article appears in the S/S19 issue of Another Man.