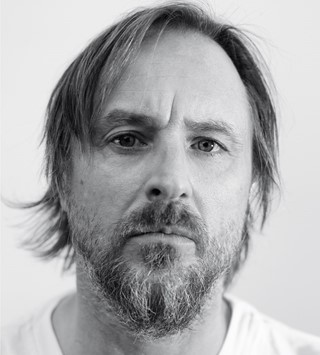

The Designer at the Forefront of Nigeria’s Fashion Revolution

- TextKemi Alemoru

Through his androgynous menswear brand Orange Culture, Adebayo Oke-Lawal is celebrating Nigerian culture, while simultaneously confronting some of its more orthodox values

It’s hard to believe that Lagos isn’t a global fashion player, given that style is intrinsic to day-to-day life there. “Nigerians are built to dress up, everything we wear is to stand out,” says Adebayo Oke-Lawal, the 28-year-old designer behind Orange Culture. Like many of his compatriots, Oke-Lawal understood the power of fashion from a young age: “You have to let your clothes speak for you before you open your mouth,” he says.

Founding Orange Culture in 2011, his androgynous menswear brand has served as a vehicle for expressing his misfit masculinity, which challenges Nigeria’s rigid gender norms – such as the idea that men are not allowed to cry. “I named it after a piece I wrote when I was 16 called An Orange Boy, which was for everyone who has been bullied for differing from the norm,” he says, after admitting that he’s never embodied the hypermasculine ideal. “It was to show that there isn’t only one type of man or woman that’s beautiful. To be honest it was a letter to myself, but when I released it online, I got lots of messages from people telling me it had helped them through a tough time. This inspired me to create a brand for those who don’t feel heard.”

Since then, Orange Culture has come far, reaching the finals for the 2014 LVMH Prize and becoming the first Nigerian brand to show at London Fashion Week Men’s. In each collection, you can see how Oke-Lawal soaks up inspiration from the dynamic environment of his hometown. “I like to totally reinvent traditional shapes into something more modern and wearable everyday,” he explains. “But my heritage is inseparable from my art.” With Orange Culture, classic African flair and pops of colour merge with Western silhouettes, while muted prints inspired by societal ills social problems are cut into wide-sleeved robes known as ‘agbadas’.

Instead of taking inspiration from conventional sources, Oke-Lawal reels off a magnum opus of debates that have influenced his designs – as if the brand is still an extension of his essay-writing adolescence. “I build prints around strong stories that we need to discuss,” he says. “I called my A/W17 collection ‘Pretty’ because I had spent time talking to boys who had been abused in school and were always told they were pretty by their abusers. Boys get abused and no one talks about it, so I wanted to bring the conversation to the forefront.”

Similarly, other collections unpack issues that he feels are neglected politically. “My A/W18 collection is about male tears – back home we were told as men that crying made us wimps.” These debates are weaved into designs. In his S/S17 collection, ‘School of Rejects’ prints were inspired by various facial structures within Nigeria’s Yoruba, Igbo and Hausa tribes. These illustrations are emblazoned across silk jackets, while hand signs children use to play on school playgrounds form motifs on delicate organza shirts. “I wanted to create a familiar place where those of us who feel lost could find happiness and feel at home.”

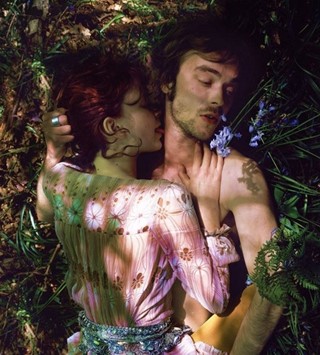

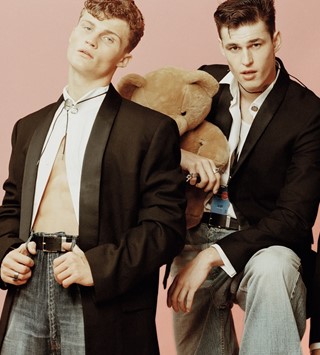

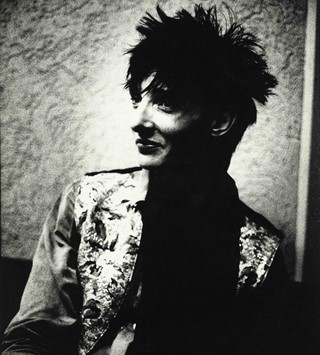

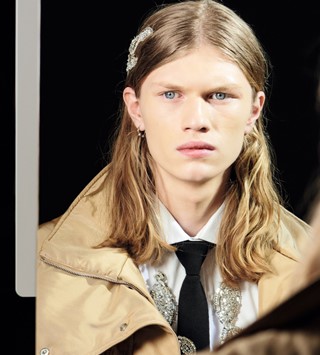

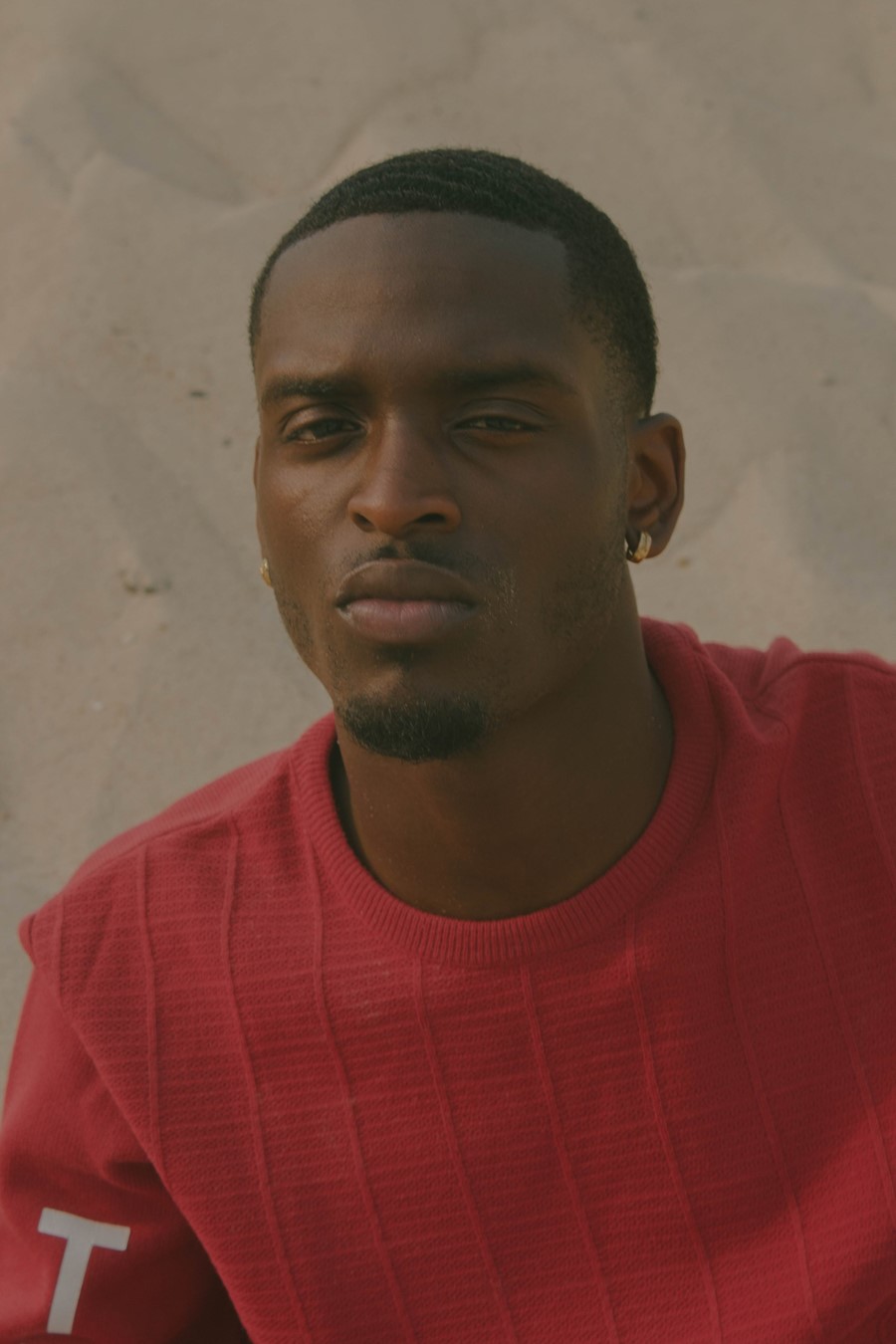

In keeping with his emotional themes, the shoot that accompanies this article, photographed by Daniel Obasi and featuring Josef Adamu, is titled ‘Alone’ because it explores the ideas of individuality. “Chasing your dreams sometimes makes you lonely,” he explains. “A lot of times I feel isolated when I’m stuck in sewing room or miles away at shows, my family are always there to remind me I’m not alone.”

Pushing boundaries and exploring divisive topics in a conservative context can be particularly isolating. Nigeria’s north is predominantly Muslim and same-sex sexual activity is punishable there by death, and conversations about gender expression are stifled. Even in the largely Christian south, you can still face up to 14 years imprisonment for same-sex relations. Oke-Lawal recounted the pressure and backlash he has received from – he often received death threats and his designs have been called “demonic”. “It’s difficult sometimes, especially in 2011 when I started, because no one was doing this. Or, at least no one was famous for doing it. I’d get horrid messages from people about what I was trying to execute,” he says. “They’d make sexuality slurs and call my brand trash. It was a heavy load. I was frequently told that I’m going to hell for playing with the idea of masculinity.”

Despite being at odds with some of its more orthodox values however, Orange Culture remains deeply rooted in Nigerian culture. Today, Oke-Lawal counts “bankers, doctors, pastors” and people in Nigeria’s most revered professions as some of his most loyal customers. That’s why the brand signals a change. It marks a shift in the Lagosian art scene that is making way for broader definitions of gender and sharper critiques of the socio-political climate, all while remaining true to Nigerian culture. And they’re ready to make their mark internationally, too.

“Even though we are far away and from a smaller and less structured scene, we’re still making a difference in the industry worldwide and that is pushing us to be bolder, louder and truer to ourselves,” he says. “Our fashion industry is on the move.” Recently Lagos welcomed the likes of rapper and Another Man cover star Skepta, supermodel Naomi Campbell and designer Ozwald Boateng for Arise Fashion Week and Homecoming festival, which showcased Nigeria’s biggest talents in fashion and music. It’s here that Orange Culture debuted some new designs at a pop-up orchestrated by director and manager to Skepta, Grace Ladoja. The trip left such an impression on Campbell that she told Reuters she left feeling so “inspired”. There “should be a Vogue Africa,” she said. “It is the next progression. It has to be.”

The region’s distinct culture is travelling organically without Condé Nast’s seal of approval, though. Infectious afrobeat sounds coming out of Lagos nightlife are seeping into British pop charts, while a newfound vibrancy has people looking at the city as the next hotspot for travel and style. Oke-Lawal credits his generation’s fearless individuality for that. “We aren't waiting for anyone to tell us how to create. We aren’t waiting for anyone to tell us how to be African or to invest in us. We are investing in ourselves.”

PHOTOGRAPHY AND STYLING, Daniel Obasi; MODEL Josef Adamu