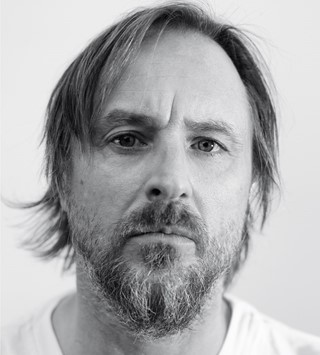

In his latest article on obsolete menswear brands, Rob Nowill considers Edward Meadham and Benjamin Kirchhoff’s men’s collections and their enduring influence

- TextRob Nowill

The Ones That Got Away is a new series by Rob Nowill that examines brilliant and now sadly obsolete menswear brands.

Is it always a bad thing when a designer stops making clothes? Over the last couple of years, I’ve read countless eulogies for the London-based label Meadham Kirchhoff, which shuttered in 2015 after over a decade. Generally, the articles follow a fairly rigid template: they bemoan the state of British fashion, the frenetic pace of the industry which causes brands to burn out, and the creative immaturity of many of the new generation of designers, whose collections lack the punch that Meadham Kirchhoff delivered. They have a point.

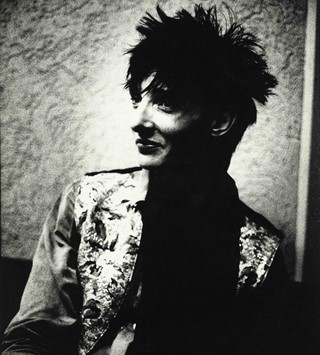

But the fact that the brand came to an early end may have worked in its favour. Young designers’ collections can feel like one idea, spread ever more thinly as they produce ever more seasons. But Meadham Kirchhoff closed just as the industry had begun to consider seriously. It left its audience wanting more. Even today, it feels as though Edward Meadham and Benjamin Kirchhoff had more to say as a duo, had they been able to. And, after their entire archive was tragically sold off in 2015, the clothes have moved into a kind of mythic space: they are unlikely to ever pop up in vintage concessions or on eBay. Despite never achieving commercial traction while the label was running, the clothes have since become incredibly desirable because they are so difficult to track down.

The menswear, in particular, feels like something of a unicorn: it never achieved the media attention of the women’s line and the collections were never picked up by any major retailers. The brand closed before it could fully articulate its point of view in men’s fashion. But the collections have gained in significance over time.

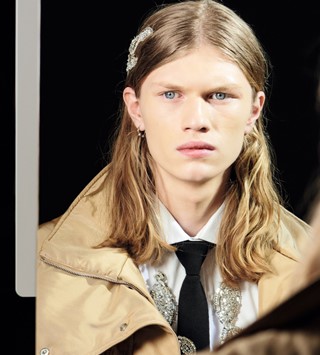

Much like Madonna’s hair, London’s menswear scene goes through clearly defined, visually distinct phases. We had the tailoring revival, led by E. Tautz and A. Sauvage. The womenswear-does-men’s moment of Jonathan Saunders, Christopher Kane and Richard Nicoll. The 90s-inflected sportswear of Astrid Andersen and Cottweiler. And, currently, a sort of nouveau non-conformism, spearheaded by designers like Art School and Rottingdean Bazaar.

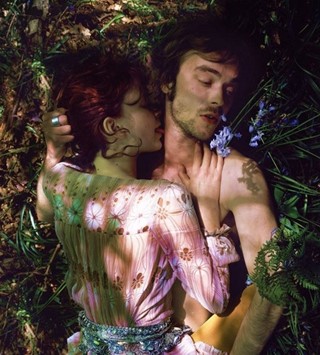

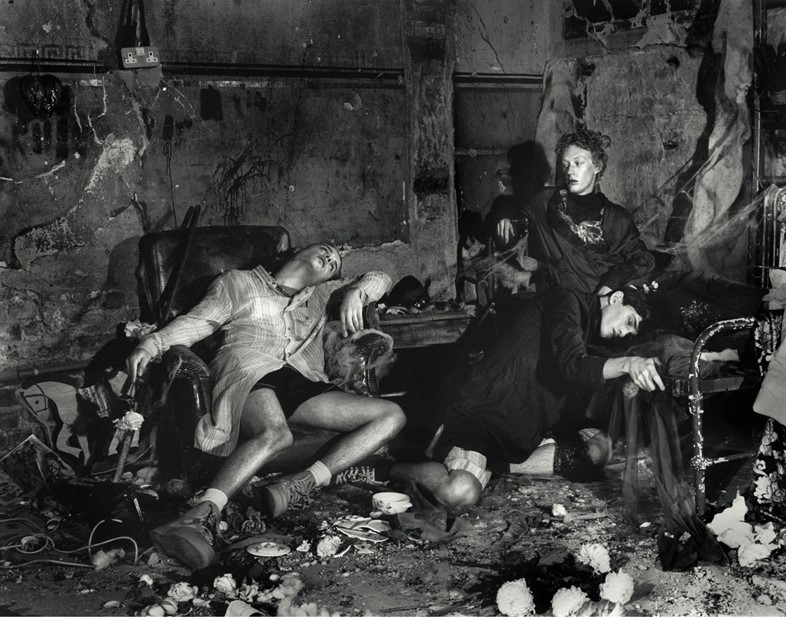

But Meadham Kirchhoff’s menswear was something of an outlier. Though it emerged during one of London’s creative booms, it had little in common with the rest of the city’s menswear scene. There was no sportswear, no print, and no irony. It resisted easy categorisation, in part because it was unconventional: collections might include grunge references, rubber, lacework and granny florals. The presentations were more akin to performance art than a traditional catwalk show.

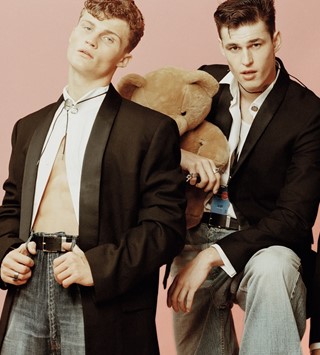

It’s unarguable, though, that during its short lifespan it helped to set the direction of where menswear is now. It anticipated most of contemporary fashion’s tics: gender-fluid casting, boy-meets-girl styling, theatrical fashion shows, and a feeling for the down-and-dirty (their first men’s collection was presented in what appeared to be a squat).

I went to see the men’s presentations at the time. I didn’t really like them. I thought the clothes were more like costume than fashion, that they were too expensive, and that they had little bearing on how men want to dress. But I underestimated their influence. Revisit the images of the men’s collections and you’ll see how many designers drew inspiration from them. It cast a long shadow over the generation of design talents that came after it.

Meadham and Kirchhoff went in different directions after the brand’s closure. Meadham launched a new label, Blue Roses, which is carried with a prestigious roster of stockists. And Kirchhoff has become a highly regarded stylist (he’s a Contributing Fashion Editor of Another Man) and menswear consultant. But what would have happened if they had stayed together? If they had found a way through their financial and production issues? If more stores had invested in their collections? I’d like to think they would have continued to be as uncompromising as they once were. But things change. Even the most progressive creatives grow up, and radicalism loses its appeal. Some things are better ending on a high.

Rob Nowill is a writer and menswear consultant who contributes to Guardian, AnOther Man, GQ and Vice

More from our The Ones That Got Away series: