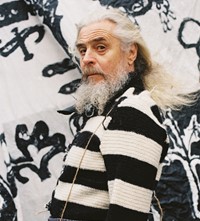

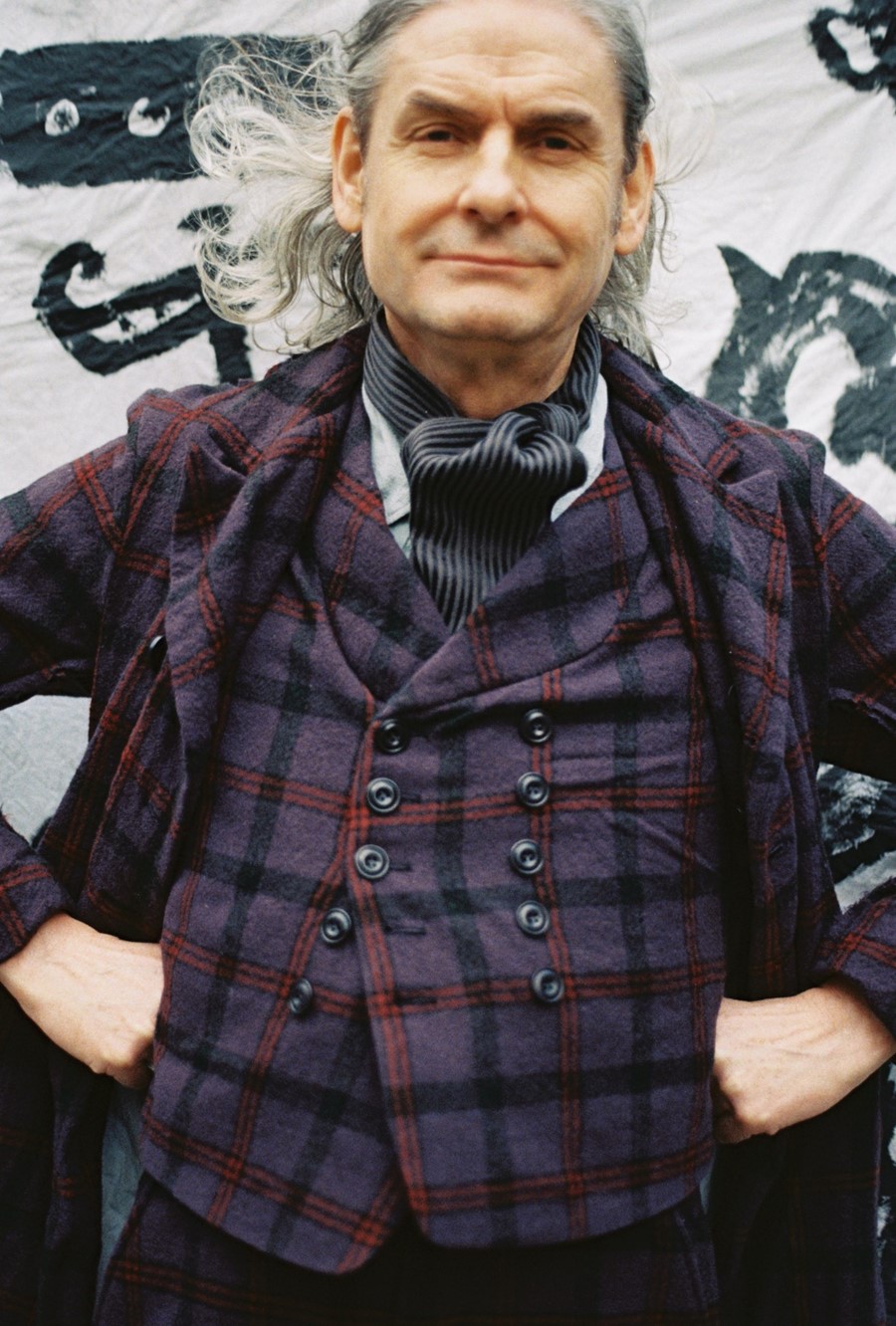

John Skelton: Fashion’s Environmental Maverick

- TextHynam Kendall

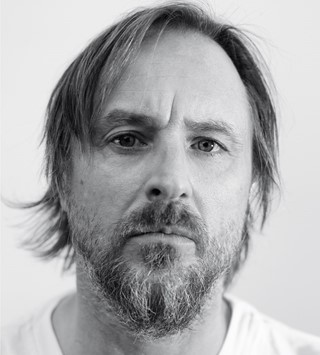

Ahead of his Fashion in Motion show at the V&A tonight, John Alexander Skelton discusses his unique and highly conscious approach to clothing

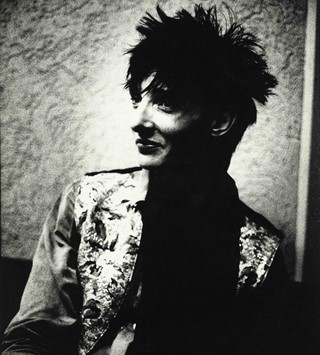

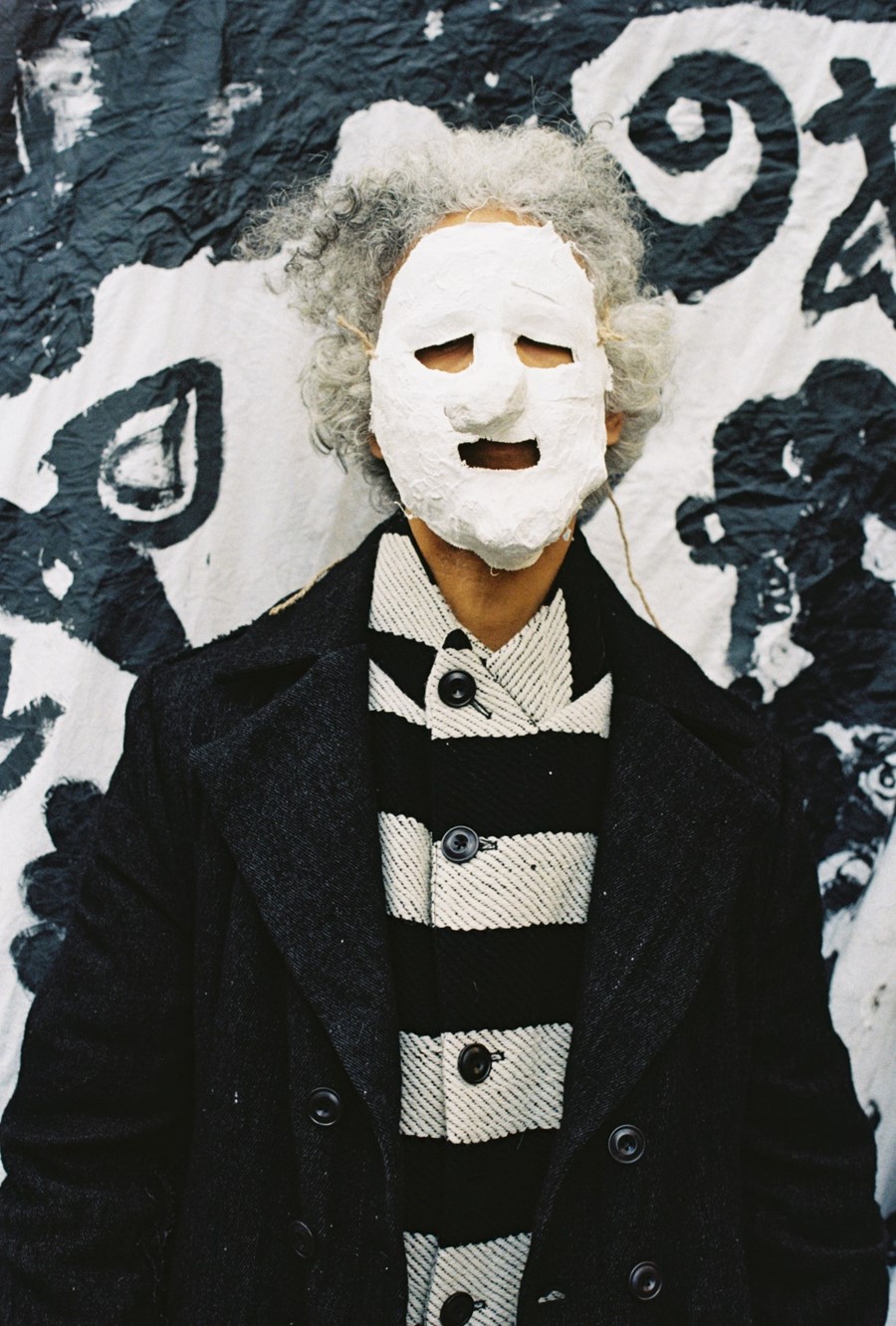

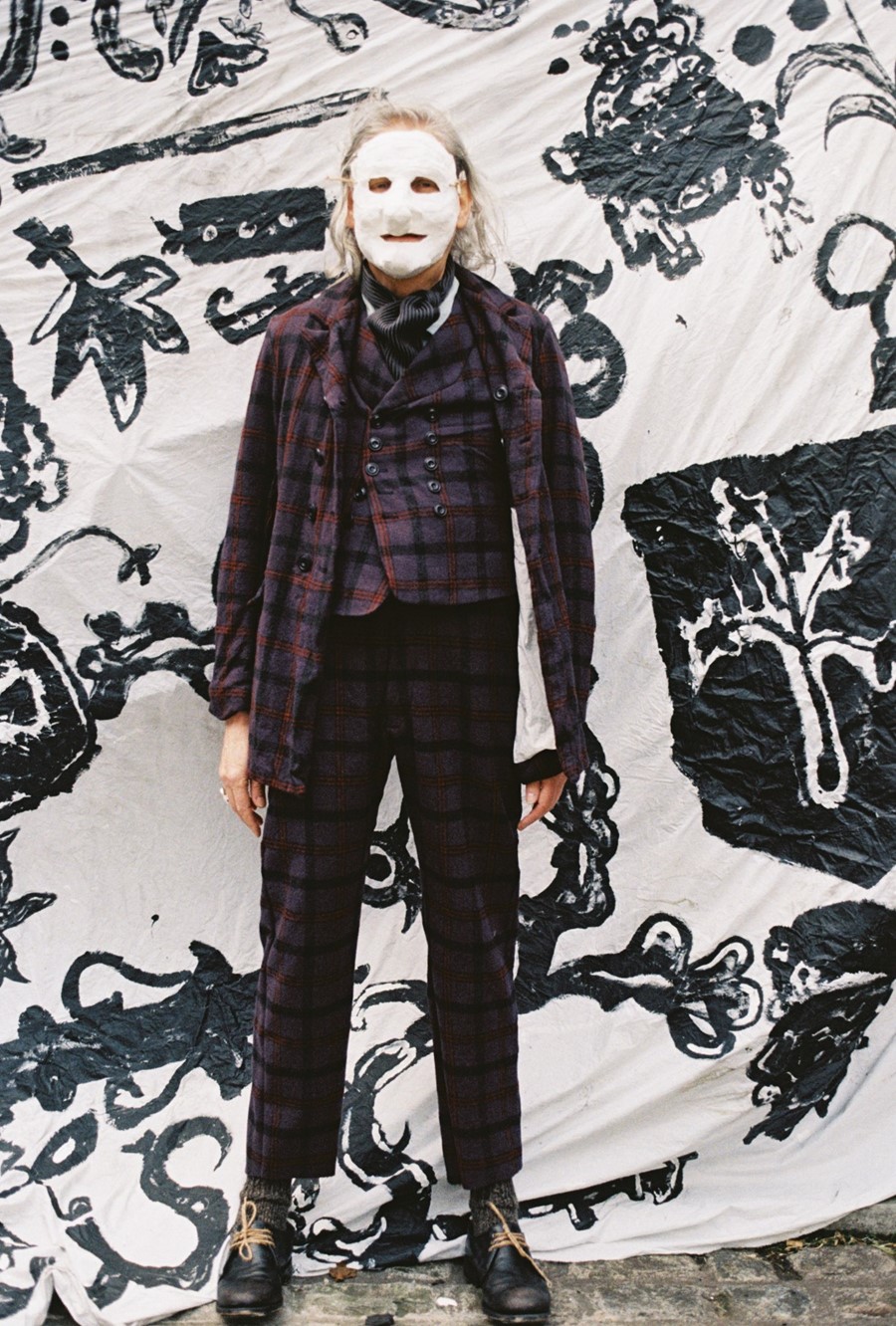

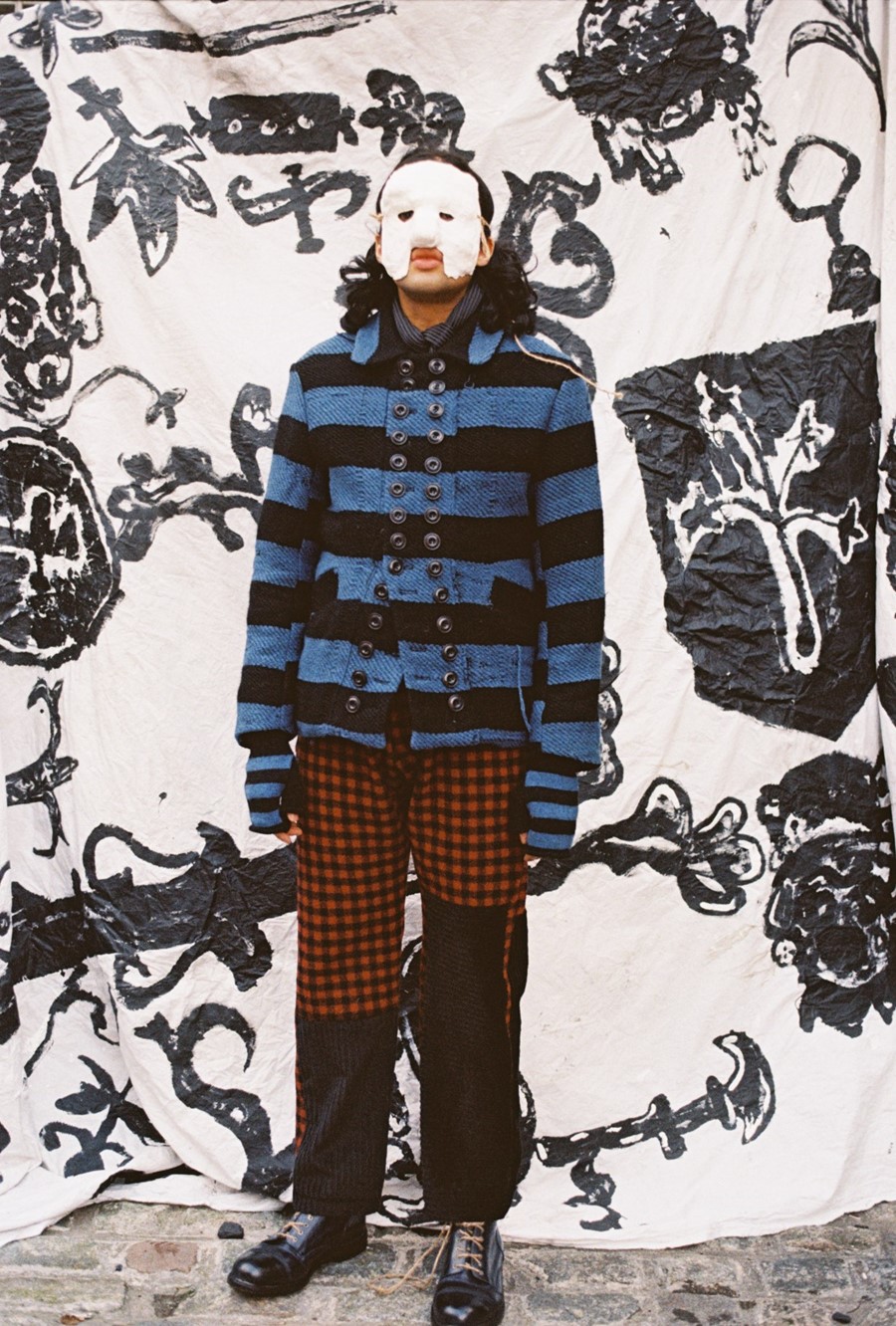

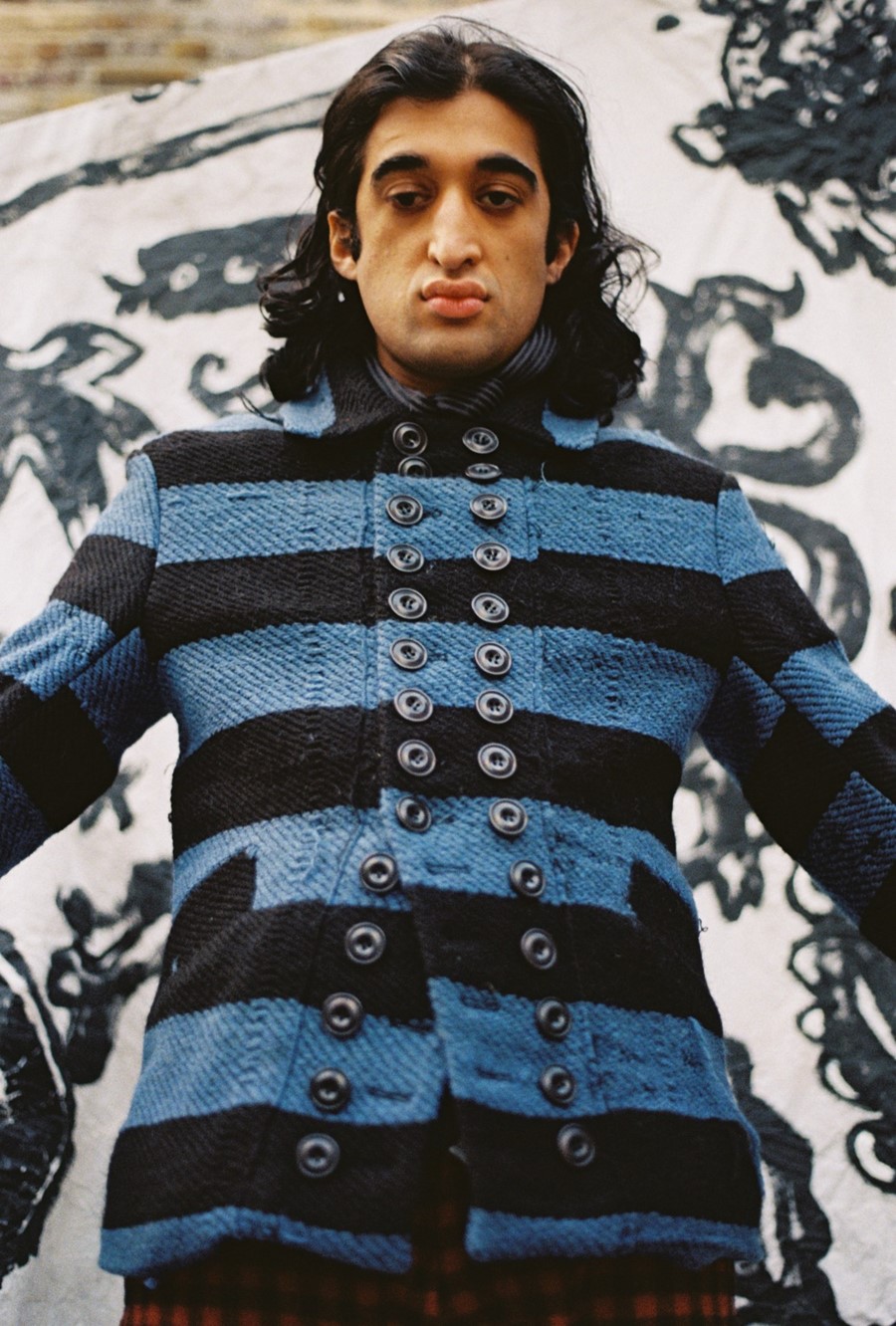

Men with faces papered white lined the walls of St Mark’s Church in Dalston. By candlelight they walked amongst you, close enough to touch, the string of their masks tied prominently to see. Which was the point. What you were watching was theatre.

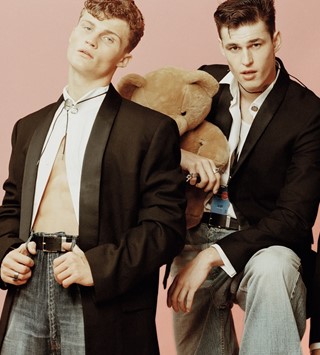

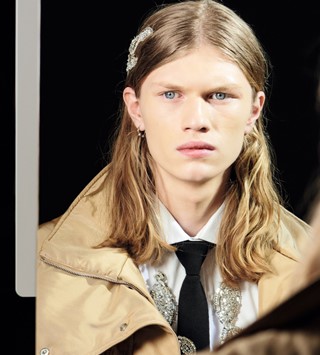

John Alexander Skelton’s A/W18 men’s collection – Collection IV – was an ode to Oral Tradition Plays and pre-industrial revolution British folk theatre, enriched with smart, anthropological references to the communities that performed them. The show – of frock coats in voluminous, antiquated overalls hand-dyed black and high-waisted trousers stringed to the body – concluded with an 18th-century dance in pairs.

Skelton’s work, by his own admission, is political. “I’m really interested in the signifiers of class and society and fashion’s relationship to both,” he says, “I am a vocal socialist, it’s just as vocal in the work.”

The A/W18 show was an exploration of ‘community’. These men he researched listlessly were weavers, were basket-makers who would, after finishing their day’s work, come together to perform for their neighbours. Skelton doesn’t try to replicate the historical uniform as costume, instead he references the culture as a physical act: ceremony, theatre, ritual practice. He is interested in the minutiae and the mundane and can spend weeks at a time trying to understand the living arrangements and daily routines of these men. He peppers his moodboards with their images in place of, say, prints of artworks that he admires, “because it’s so much more important to our lives,” he says. “Because of this [my work] can be seen as a personal manifesto. It often speaks of my anti-individualist politics. I am against a selfish society. Individualism can breed fear, can lead to pushing away people who are ‘other’ away. We’re seeing it now with Brexit.”

Among those present at Skelton’s A/W18 show was Oriole Cullen, a prominent curator from the V&A Museum who had been turned on to Skelton by the milliner Stephen Jones. (Jones has collaborated with Skelton since his Central Saint Martin’s graduate collection in 2016.) Soon after the show, an offer came from Cullen for Skelton to transpose his theatrical flair to a museum setting, as part of the V&A’s live catwalk series Fashion in Motion. Skelton accepted almost immediately.

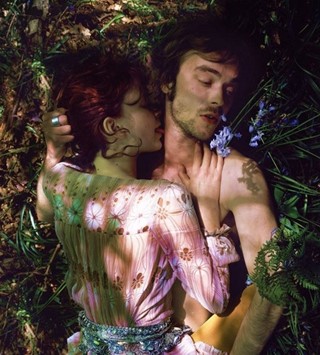

“Being outside of the fashion week calendar means that the public, people who are not in the business who otherwise wouldn’t be able to see a fashion show, can have the opportunity to,” he says, “which you can imagine really speaks to my socialist politics.” He had seen Meadham Kirchhoff’s 2013 Fashion in Motion show, too, and marvelled at the “excited feeling” of the room. He describes it as a community feeling.

As well as his “Dickensian aesthetic” (Skelton's own words), it’s his refusal to adhere to the prescribed way of working that caught the V&A’s attention – as well as that of the wider industry, including the Lee Alexander McQueen Foundation who awarded Skelton the Sarabande scholarship just over 18 months ago. He follows in a superlative lineage including Craig Green and Molly Goddard.

Skelton produces only one collection per year and, in a bid to promote sustainability and ethics within the industry, often uses historical methods to achieve a more ethical product. He hand dyes every garment himself and creates the dyes using old processes discovered in his extensive research. He works in tandem with nature to achieve the colours, for example boiling down rust or coal for black – “like they did traditionally in Japan to dye the kimonos. “There’s not a lot of information out there, so you really have to just try it to understand it. It requires forensic research and trial and error.” Last season Skelton even used his own urine as a mordant and a fixative for dye – a practice employed for many years up until around the mid-19th century. Apparently it works well with wool and cotton, though the scent can be “intoxicating”. “I sometimes felt high!” he laughs.

Skelton also sources almost exclusively from within the UK [only sourcing some hand-spun fabrics from India out of necessity]. His biggest wish is that fashion brands try and reduce their carbon footprints as much as possible. He breaks down tracking of a simple garment which can, he assures, have visited as many as six different countries before reaching the consumer. Skelton prides himself on the fact that he could tell any customer where every single element of his design was sourced, grown and made, as well as its full trajectory from his workshop to their wardrobe. This is his motivation not to succumb to selling online or via e-tailers. As well as wanting the customer to “experience the clothes and see them and touch them, to try them on, to actually understand what they are purchasing.” He much prefers the tactile ritual of old, he says.

When I say it would be safer for him to adhere to at least some of the tried and tested ways of working, Skelton laughs. “I feel that ‘safety’ is an awful thing that has been allowed to happen to this industry,” he says, “safety in design, safety in the way we design, safety in the way men dress. In the way we make and the way we sell.” He takes a beat and chews the word safety around his mouth in repetition. “The good thing about safety,” he finishes, “is that it gives me something to push against.”

Fashion in Motion: John Alexander Skelton is happening tonight at the V&A Museum. Head here for more information.