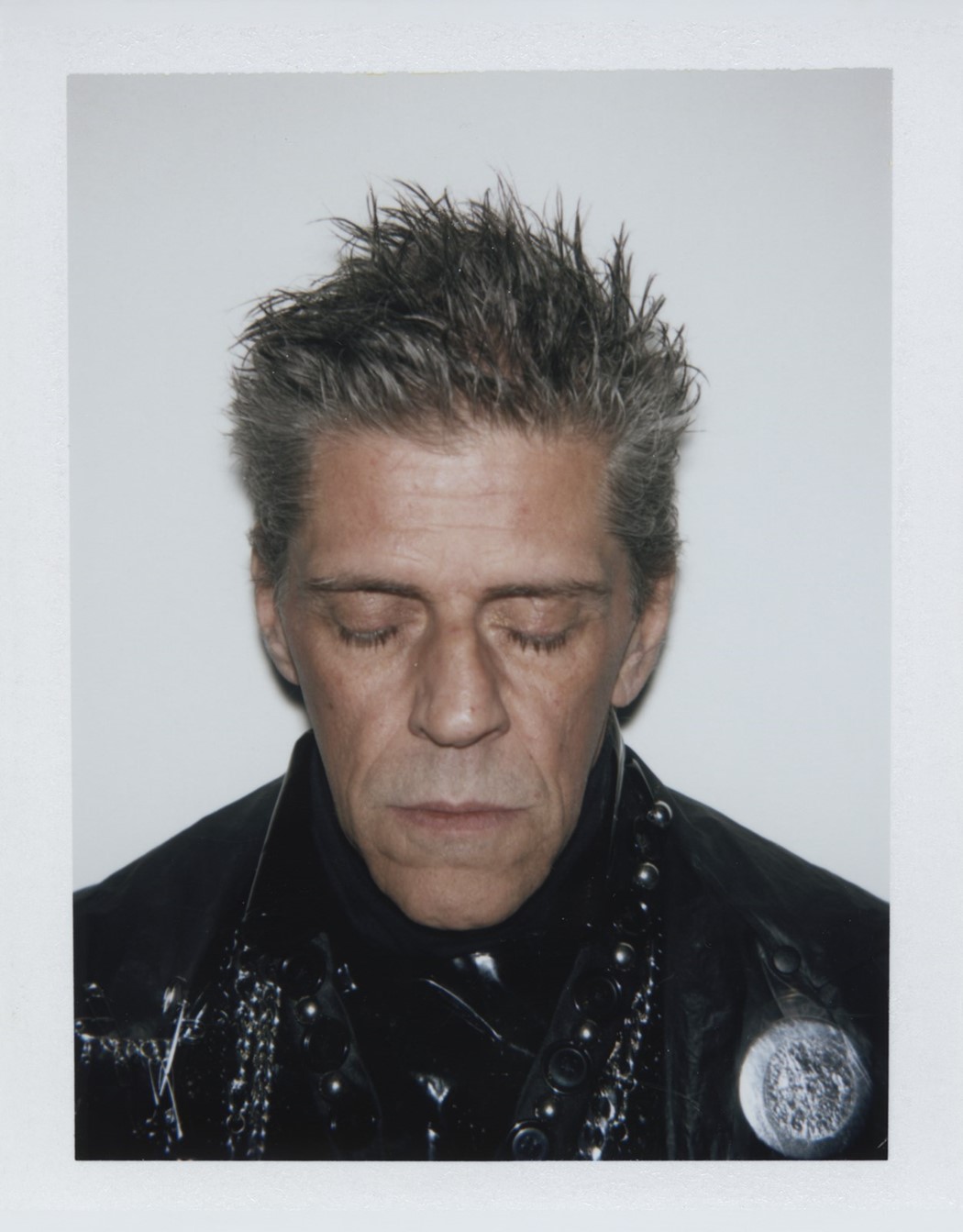

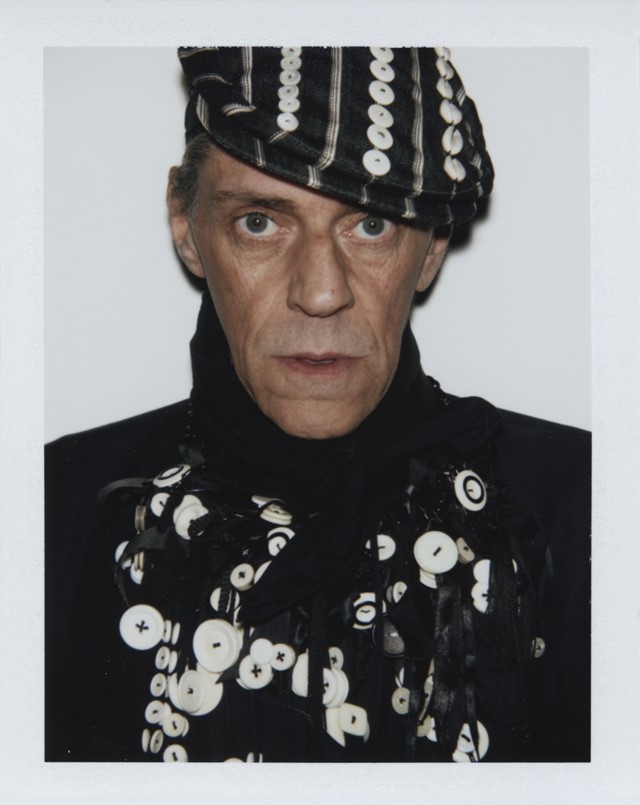

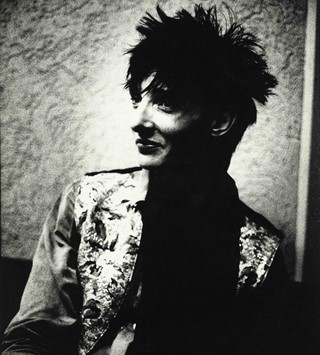

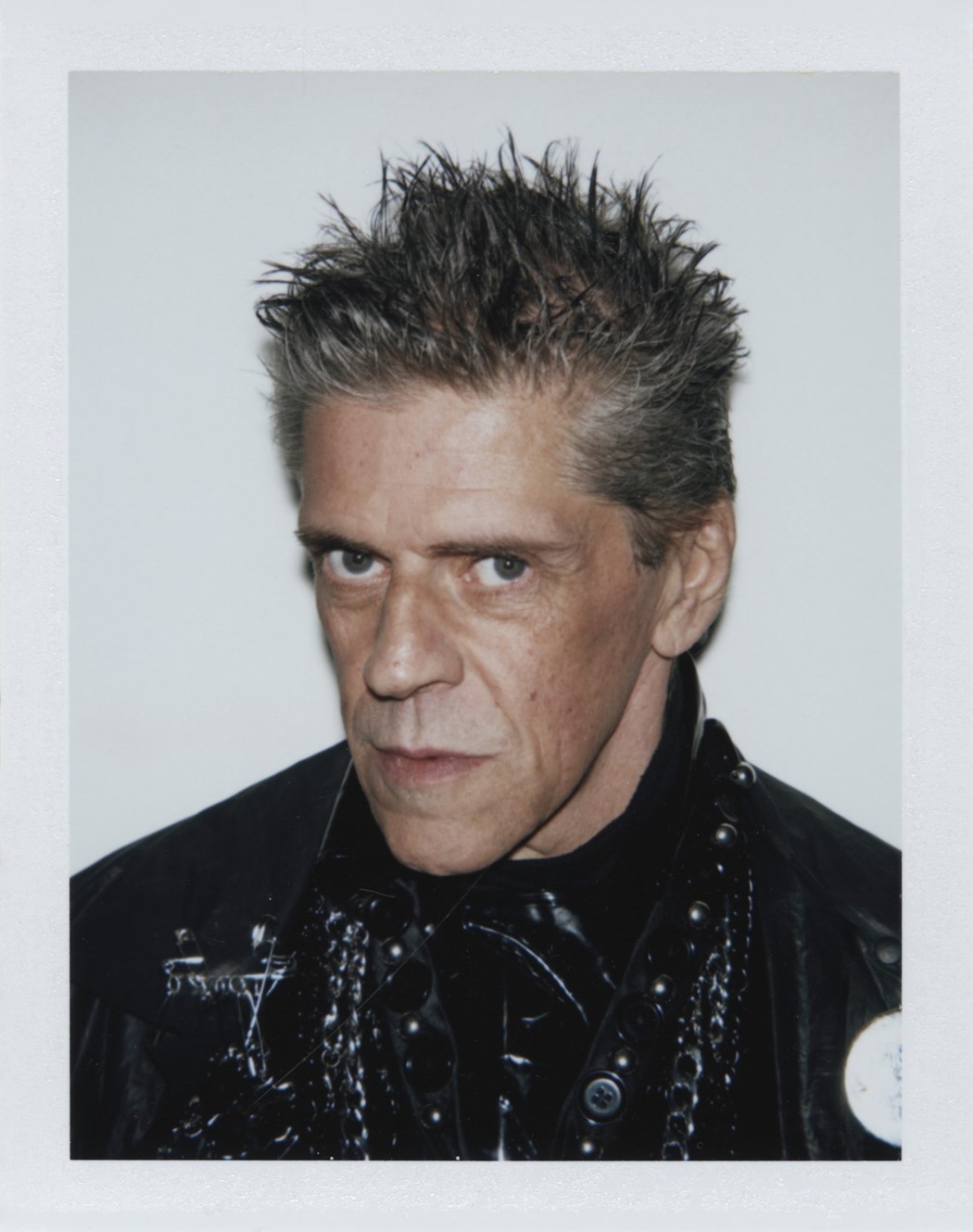

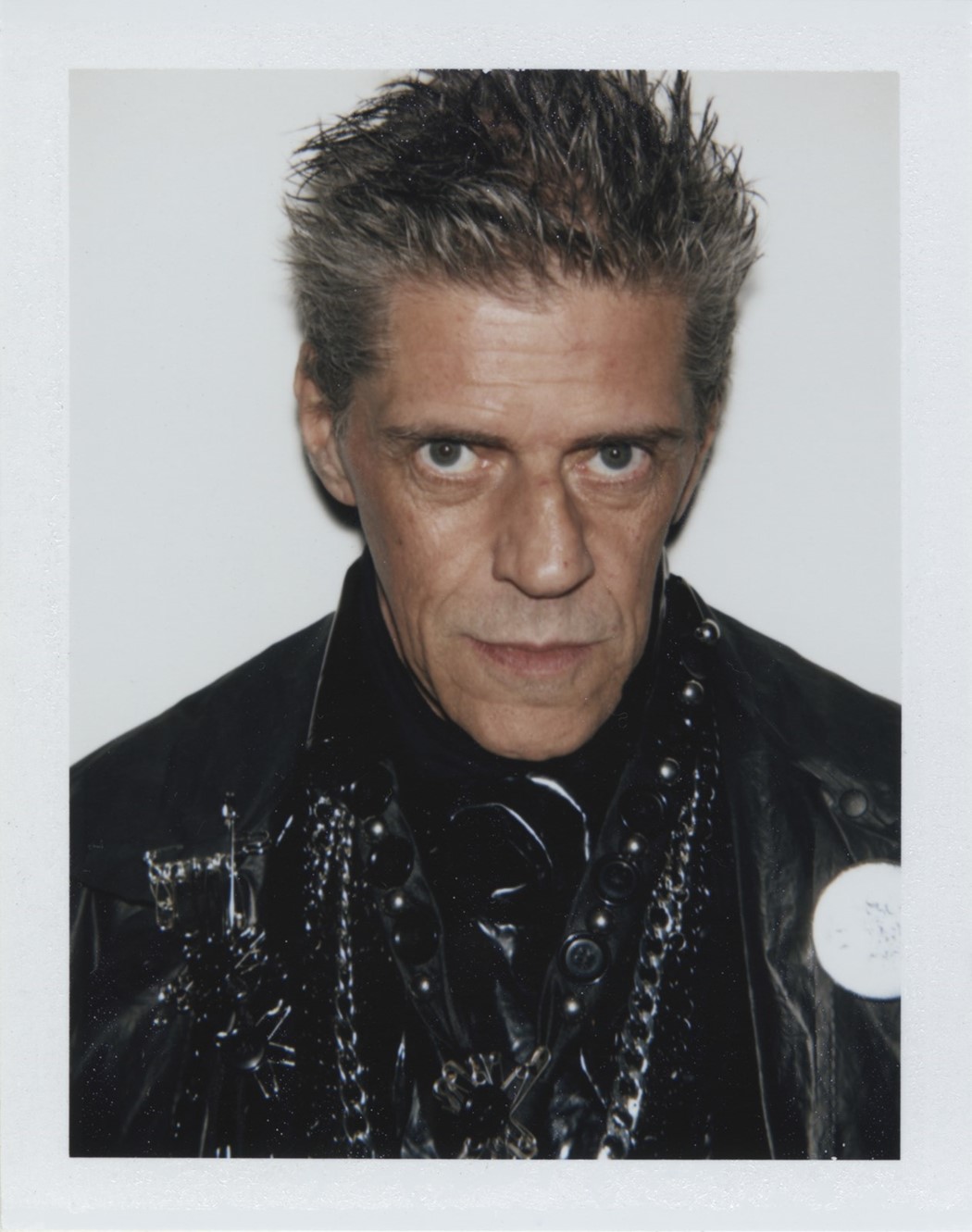

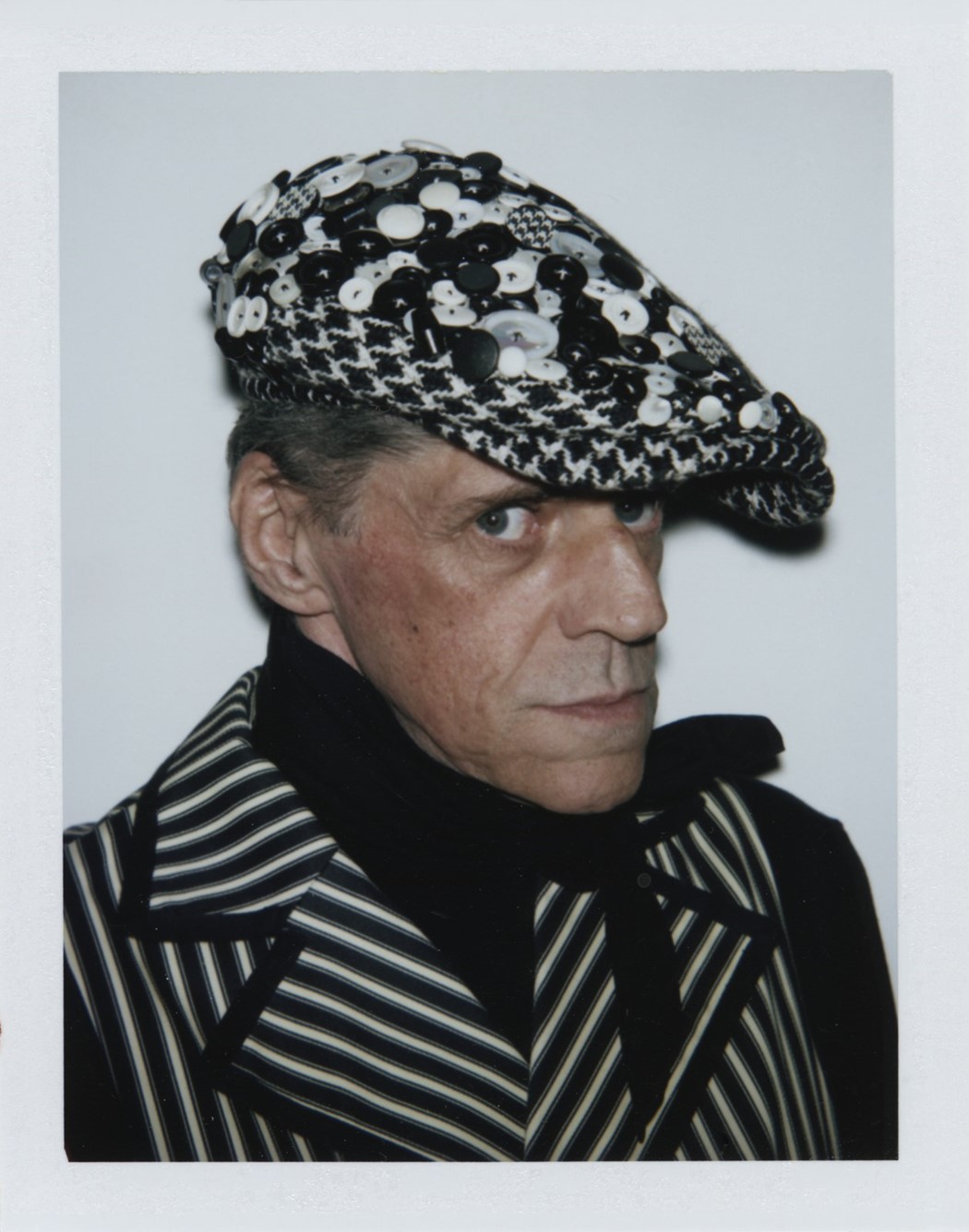

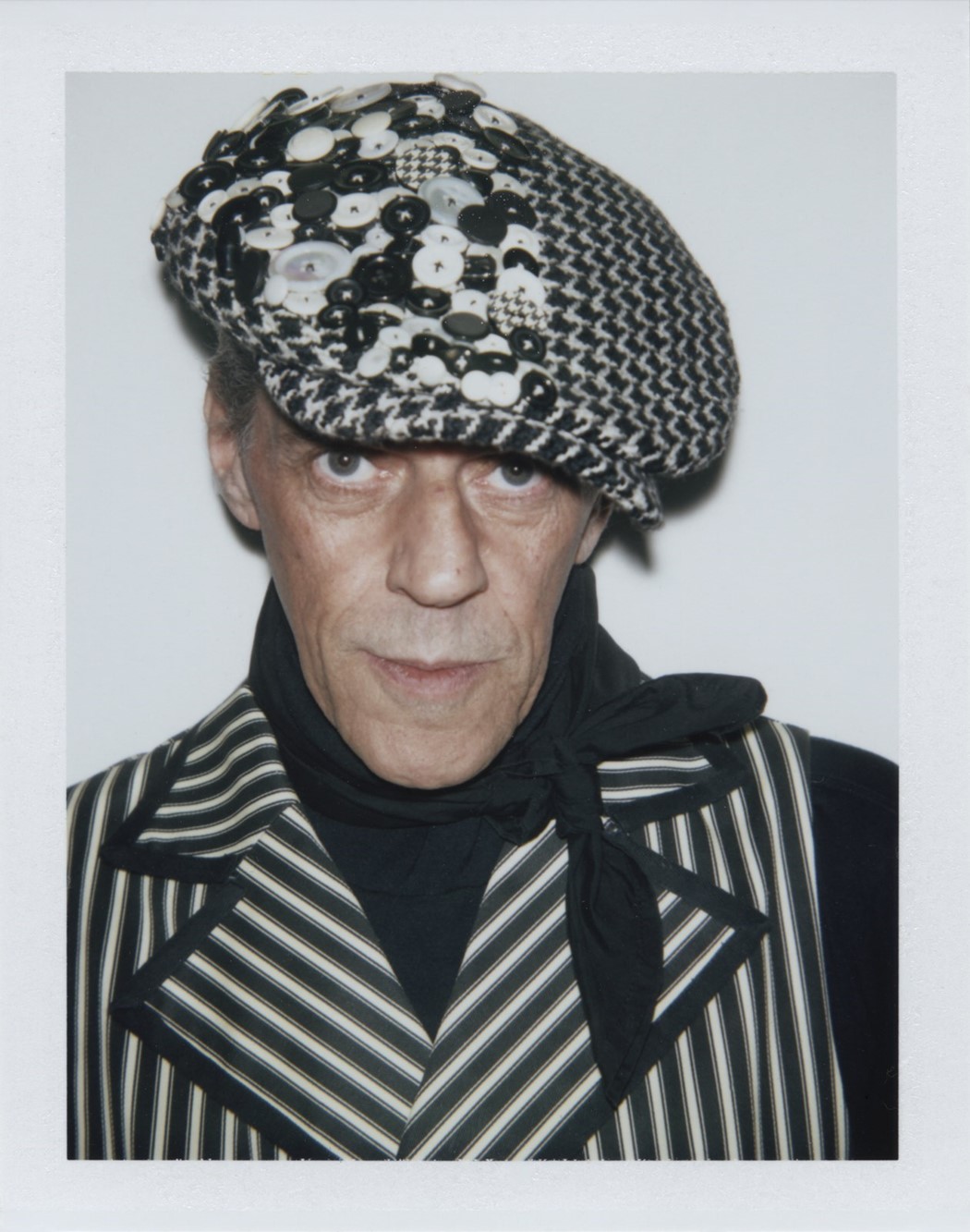

Judy Blame: In His Own Words

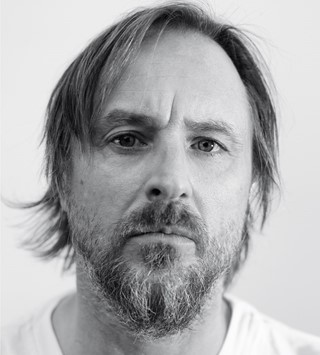

- TextTed Stansfield

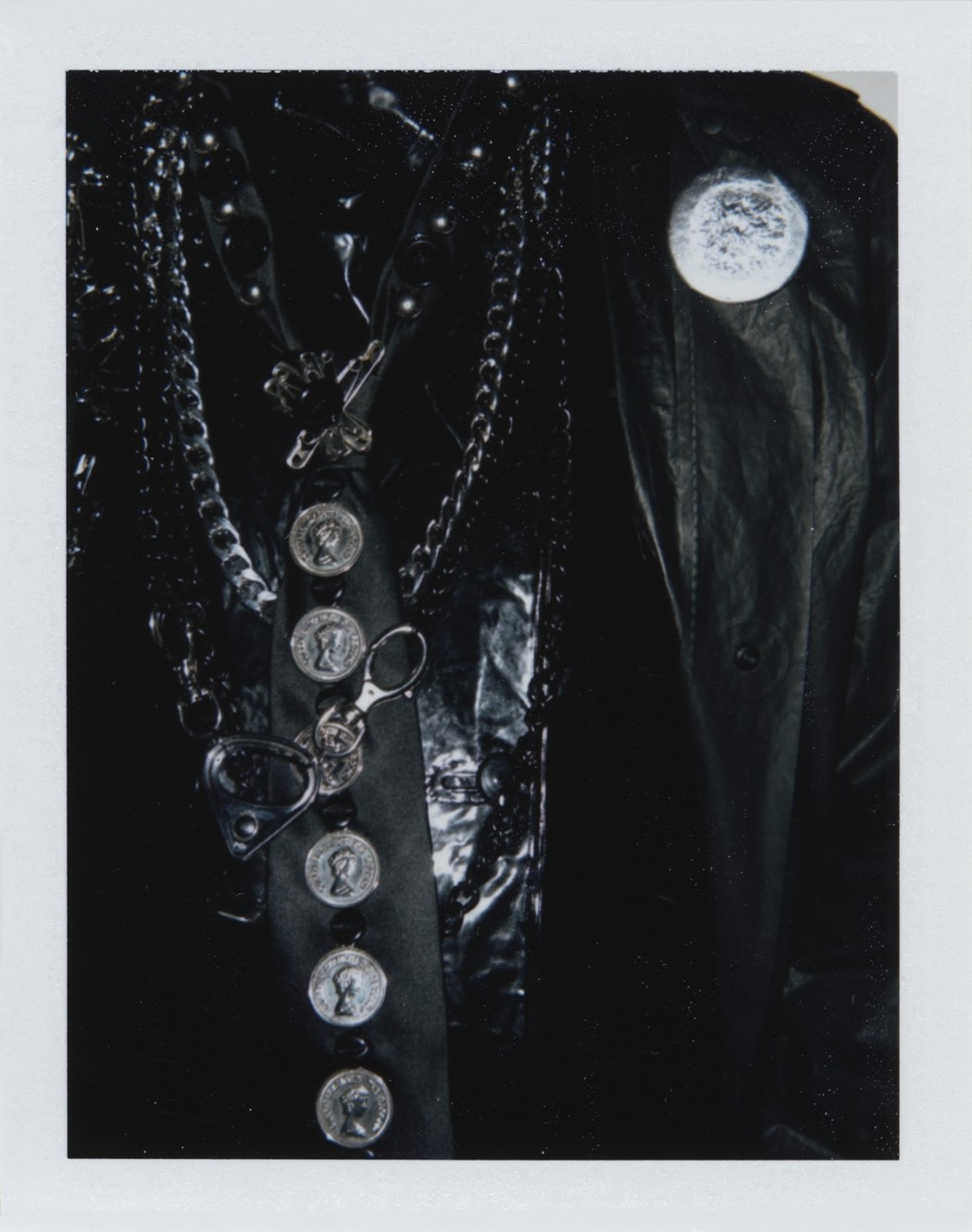

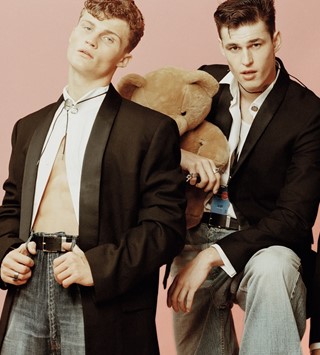

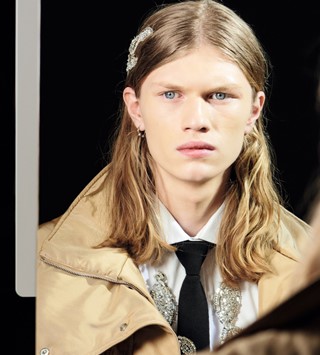

- PhotographySamuel John Butt

Read an unpublished interview with the late, great icon

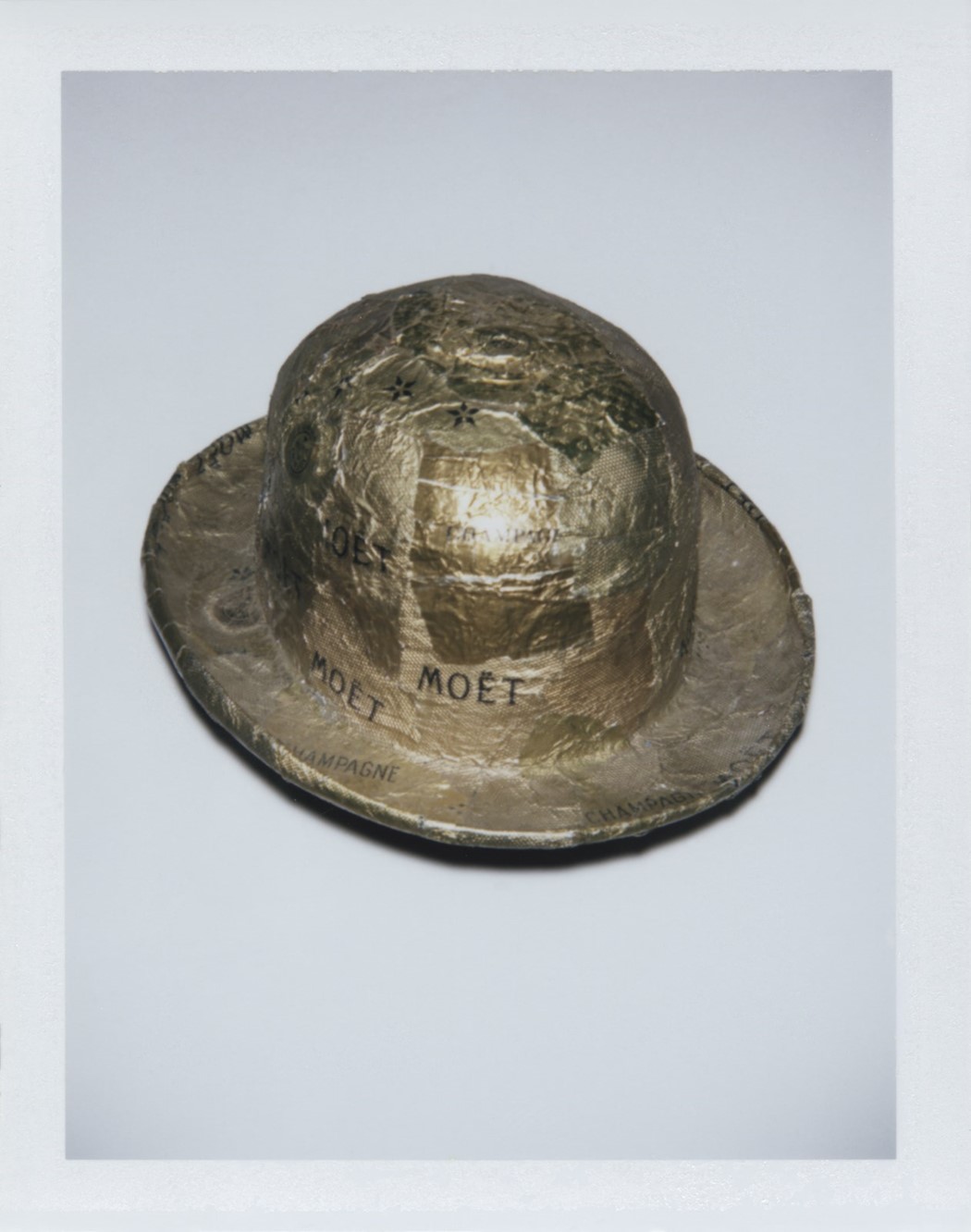

Judy Blame was an icon and an iconoclast. An accessories designer, art director and fashion stylist, yes – but so much more, too. Blame helped craft the look of the 1980s – first through his work with Ray Petri and his collective Buffalo, and later through the boutique, design studio and the House of Beauty and Culture crafts collective, which he set up with his friend John Moore. A true original and ingenious craftsman, Blame had the power to transform bones, clay pipes and coins dredged up from the Thames into fabulous accessories, and do much more besides. While his clients and collaborators traversed the worlds of fashion and music – from Kim Jones, John Galliano and Marc Jacobs to Boy George, Björk and, of course, Neneh Cherry – he never compromised, staying true to his vision and his wholly punk ethos. Here, in a previously unpublished interview full of wit, wisdom and Judyisms, Blame tells his story in his own words, reflecting on his childhood, career and collaborators, plus his celebrated encounters with Rei and Ray.

TED STANSFIELD: So how did you begin making things?

JUDY BLAME: Well, I was never trained; I never went to college. Punk rock – that was my training. Whatever I’ve done, I’ve had to pick it up and work it out for myself. And because I wasn’t trained, I haven’t got that baggage.

TS: So do you think your lack of training has been beneficial?

JB: Yeah, because training can hold you back, especially with fashion. I love breaking the rules all the time. You know, when people say, ‘Ooh, you shouldn’t wear red and green’? There’s always some kind of rule. I love tradition, funnily enough, but if I’m told not to do anything, I want to do the complete opposite.

TS: And that’s punk?

JB: It’s something to do with that.

“I was never trained; I never went to college. Punk rock – that was my training” – Judy Blame

TS: Do you think there are any rules left to be broken?

JB: There’s always something to rebel against. With punk, we did want to break the rules. We were bored. London, England was really depressed. It was a dark, grey time. So that’s why it started. There was something about the spirit of starting again. ‘We don’t care about these big bands, we don’t care about clothes, we don’t care about the way we look, we can’t even play our instruments, we don’t care.’ People mistake it now, they think it’s just a look. Punk wasn’t a look, it was an attitude of the young people.

TS: So do you think punk is dead?

JB: Well, they keep dragging it back, but the only thing they keep dragging back is the look of it, so it doesn’t mean anything to me.

TS: Do you think there are any punks in culture now?

JB: There’s always someone causing trouble, I hope, and if there isn’t, there’s always me. There will always be an underground, whatever’s going on upstairs. I think the world’s in a similar (place) now... There are a lot of problems. But it’s on a different scale to when I grew up.

TS: So tell me about growing up. You’re from Devon?

JB: Well, that’s where I ran away from. Near Exeter on the edge of Dartmoor, a little village. I didn’t really get on with the countryside. By the time I was 13 or 14, it was all about Bowie and Bolan, and the last place you wanted to be was in the countryside. And by the time punk came around, I was like ‘I’ve definitely got to get out of here.’

TS: So how did you get out?

JB: I had a summer job as a waiter at this tourist spot, near my village. I saved up what I thought was a fortune at the time, but it was about 300 quid or something. I didn’t even tell my parents – I just went, ‘Oh, I’m just going to visit my friend in London.’ I’ve never looked back.

TS: What was it like when you arrived there?

JB: It was fine. I went to see Iggy Pop at the Rainbow, went to Vivienne’s shop, bought my bondage trousers, dyed my hair orange, and I was ready for it.

TS: What kind of things did you wear?

JB: We used to have this brilliant hairdresser called Ross Cannon and my friend Scarlett was a really good friend of his. He was a genius with a pair of clippers and stuff. So I used to have a Ross hairdo, and my jewellery.

“That’s where it started, in the nightclubs. You met everyone there” – Judy Blame

TS: How did you start making jewellery?

JB: Just to go out with. Every weekend we would go to a nightclub and make a massive piece of jewellery to go out with. One week I’d be like, ‘Chains!’ and the next I’d be like, ‘Bones!’ or something. That’s where it started, in the nightclubs. You met everyone there. I would turn up every week with a piece of jewellery, and it went from there.

TS: I read you made jewellery out of things you found in the Thames...

JB: It’s called mudlarking.

TS: What sort of things did you find?

JB: Well, it was great for bones. Really nice, old bones.

TS: Human bones?

JB: I don’t know what they were – could have been anything! Clay pipes, it was really good for that. Just really nice beaten-up old things, you know. Every now and then you find a bit of treasure like old coins, all kinds of things.

TS: You’ve made jewellery for all kinds of people. Out of curiosity, what was it like doing it for Rei Kawakubo?

JB: It was funny, because I’d always been a fan of Rei – I remember seeing her early shows in Paris when she was shocking them silly. So when I got the call, I was like ‘Oh my God, at last!’ We arranged to meet her at her hotel. I was about three minutes late, sweating, dragging my bag and there she was, sitting there like Adolf Hitler, surrounded by her staff. She just pointed at this piece I’d brought, which was made from gold chains and fluorescent pink toy soldiers and said, ‘I want that.’ I left the meeting thinking, ‘Did she really want that?’ I rang Adrian (Joffe) a couple of days later and said, ‘Adrien, what does Rei want me to do?’ And he said, ‘She doesn’t care what it is, as long as it’s pink and gold.’ That was my only instruction: pink and gold! So it was nerve-racking, but brilliant. The collection was (very) Pink Panther – all these mad suits that looked like they’d been made out of furniture fabrics.

TS: Which collection was it?

JB: I mean, it was a while ago now... Spring/summer 2005? When she saw it she sent it out twice, so she must have liked it. Then I was stuck doing gold chains and fluorescent soldiers for about six months!

“I’m glad [Ray Petri] had an influence on all that was going on. Particularly on getting people of colour into the business, because at the time it was a bit honky” – Judy Blame

TS: And can I ask you about another ‘Ray’, Ray Petri? What are your memories of him?

JB: Well, Ray was one of the ones who got me going. He was very encouraging to me about starting up. I adored him, everyone did. He was just cool. He’d borrowed a lot of stuff off me and, I don’t know, we just became friends. And, yeah, they definitely don’t make them like him any more.

TS: What was the most amazing thing about him?

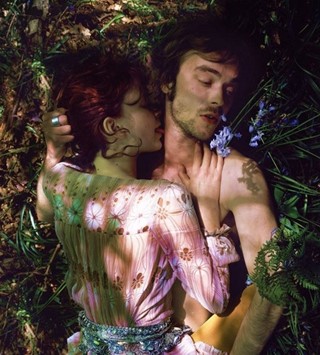

JB: I suppose looking back, I’m glad he had an influence on all that was going on. Particularly on getting people of colour into the business, because at the time it was a bit honky. He was at the forefront of mixing sportswear with smart clothes, with fashion. You know what I mean? On a black man. It doesn’t sound like anything now, but it really was.

TS: How would you describe the spirit of Buffalo?

JB: Pride is how I’d describe the spirit of it. Pride. That’s why Neneh Cherry called her book Buffalo Stance, because there was a pride about it. At the time, a lot of people didn’t rate it. They just knew it was cool because it was in The Face. Then there were a (lot) of people who didn’t even talk about it. Now, younger kids who come across it get it straight away. It’s come back; I think Ray is more influential now than he probably was then. It just goes to show that a good idea can last forever. There was a kind of gang mentality to it. I’m not saying it was a gang because anyone could be a part of it; he was that kind of person. It was definitely Ray finding people who had something.

TS: What was that something?

JB: I don’t know. Ray would find it if you had it, though. And it wasn’t always because they were a fabulous-looking guy. There would always be something else. Brilliant casting.

TS: He said that came first, didn’t he?

JB: He always told me to think of the person first, the picture second and the outfit third. And he told me to believe that that person would wear it. If you look back, some of those outfits are really camp, but because they’re on the right guy it works. Ray’s favourite thing to do was to get them dressed and brush their shoulders, just to settle them down before they stepped in front of the camera. It was like a gesture, a kind of, ‘You go, boy’ – I don’t know... Because these boys were like, ‘I don’t know what I’m doing with a shirt with a penis on it, or a jacket with a fox-tail hanging off it, or a Russian medal.’ But he’d make it feel like the best thing. He was special. He made you believe in yourself. He had a knack of saying, ‘Why don’t you do this as well?’

“A good idea can last forever” – Judy Blame

TS: So he had a more collaborative approach?

JB: Now, it’s all ‘It’s mine.’ Back then, it was more like ‘I’ll help you,’ and ‘Why don’t we do it together?’

TS: Who were your most crucial collaborators?

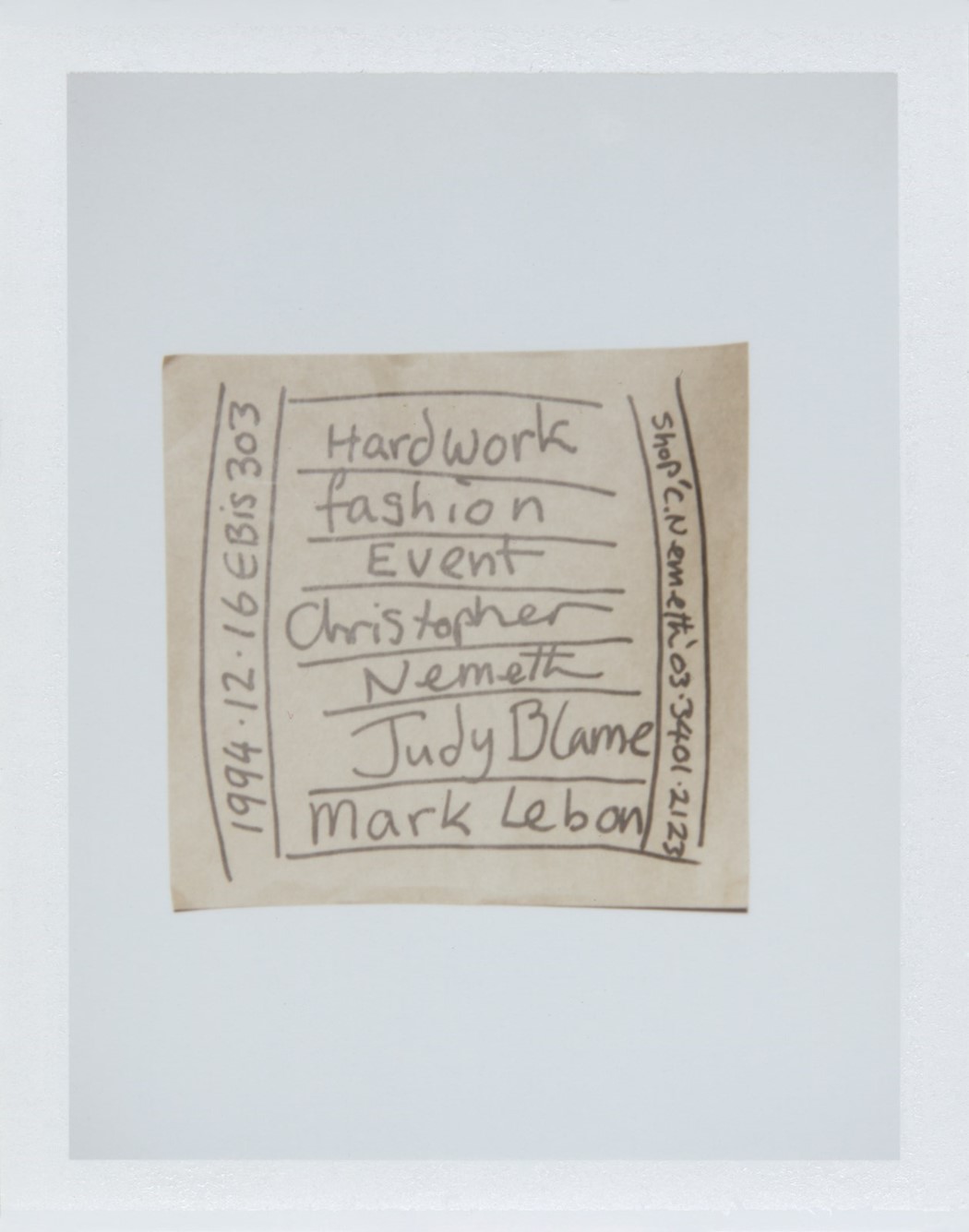

JB: I’d say the most important one was Christopher Nemeth. The first time I saw his clothes I thought, ‘Well, if I made clothes, that’s what they’d look like.’ I was knocked out by them. He was using very similar themes to me, like recycling things, and he had the same abstract mind because he wasn’t coming from a fashion perspective, he was coming from a fine art perspective. And the whole thing about his clothes was that he made them because he needed them. He needed them to last, so he made them out of post sacks... There was something about it. Apart from that, he was a lovely bloke and we used to get on like a house on fire. I think we thought totally along the same lines. Doing this show for the ICA, I’ve had to look backwards a lo. I hate doing that normally, but I’ve had to – to see what I’ve got left, what I’ve managed to cling on to, and how can I illustrate what I do.

TS: What is it that you do?

JB: I don’t know what to call it any more. I exist.

In memory of Judy Blame: 1960–2018