For the final part of his series on hip hop style, Calum Gordon explores Gucci’s relationship with rap

- TextCalum Gordon

Whether it’s Gucci and Louis Vuitton riffing on the work of Dapper Dan, or the contemporary streetwear labels building on the foundations of early pioneers like Stüssy and X-LARGE, hip hop’s influence on how we dress in undeniable, and fittingly, impactful. Each epoch of this subculture turned de facto pop culture has come with its own host of styles and labels. To chart each one – often specific to regions or neighbourhoods, or trends with limited lifespans – would be impossible. But some brands have left a lasting impact, either stylistically or on how we have come to view hip hop as a driving force within contemporary fashion. In The History of Hip Hop Style in Four Brands, which coincides with the A/W18 men’s shows, we look at those brands whose wares or influence continue to resonate.

This week, Miami-born rapper Lil Pump’s track Gucci Gang went platinum. The song is a very particular brand of luxury earworm, notable for its refrain of: “Gucci gang, Gucci gang, Gucci gang, Gucci gang / Gucci gang, Gucci gang, Gucci gang (Gucci gang!)”. Asinine but very catchy, it takes the Italian fashion house to the point of satiation, as thoughts of Alessandro Michele’s work and Gucci monograms become obscured by a more abstract concept of the brand.

Founded in 1921 and initially specialising in leather goods, Gucci has been referenced by rappers since the very beginning of hip hop. Outkast did it, Ghostface Killah too. Atlanta rapper Radric Davis went as far as far as adopting the moniker ‘Gucci Mane’. Future, meanwhile, famously pronounced that he’d engaged in intercourse with “your bitch” while wearing Gucci flip flops, and ‘What’s Gucci?’ replaced ‘What’s good?’ in the hip hop lexicon, thanks to Kanye West. But, save for the odd Gucci monogram or red and green stripe motif, Gucci has been used in a host of rappers’ work as a way of denoting wealth and taste, without having to spell it out explicitly. The brand’s heritage speaks for itself, playing into a notion of luxury which acts as a counterpoint to most rappers’ humble beginnings.

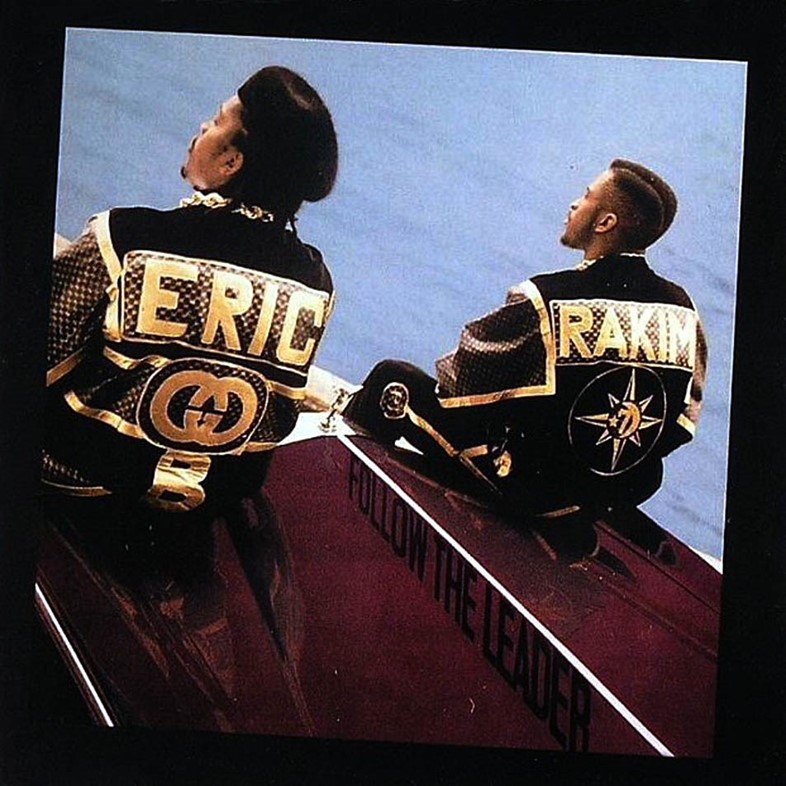

That heritage was a cornerstone of the aesthetic of Dapper Dan, a seminal figure in hip hop’s sartorial past. In the 1980s, the Harlem-based tailor took the branding of luxury fashion houses, such as Gucci, and created street-ready garments and sportswear – something that even extended to luxury furs and car interiors. Loud, bold, branding front and centre, he made track jackets featuring Gucci’s monogram for Eric B and Rakim, who were two of his earliest hip hop customers. Rakim himself would go on to push rap into a new direction, forgoing the traditionally stilted couplets of his older peers in favour of smoother, more elastic bars.

“If I have a roll of fabric, it’s anything I want it to be,” Dan said in a recent documentary titled Fresh Dressed. “Anything a designer didn’t have, I would embellish it for them. I blackenised it. I made so it’d look good on us. I took it where they would never take it… I never realised the impact it was making, I just wanted to serve my community.” When Gucci debuted its 2018 Resort collection in May last year, including designs starkly reminiscent of Dan’s, it once again raised questions about fashion’s appropriation of hip hop and black culture. Indeed, it was Gucci, along with a handful of other luxury labels, that put Dan and his 24-hour Harlem atelier out of business in 1992.

Today, Dan’s designs of the 80s and 90s – sportswear emblazoned with luxury motifs and beautifully tailored outerwear accented by bold logos – look prescient, amidst a sea of brands adopting similar creative practices. Meanwhile, Gucci has since attempted to make amends to Dan, opening a new store with him in Harlem and placing the New York designer, as well as casting him in their A/W17 tailoring campaign. But, as fashion writer Jason Campbell observed out, the brand has benefitted plenty from black creativity and style. “It seems only fitting that Gucci which has never really had an inclusive mandate finally adds some melanin to their roster,” he wrote in October. “In addition to occupying the number one spot for name-checked brands in hip-hop music; Gucci’s renaissance has landed big, literally on the backs of black community from Lagos to the ATL; it’s Gucci down to the socks for anyone concerned with style cred.”

Campbell is correct, Gucci is the most name-dropped fashion brand in all of hip hop. Part of that is simply linguistic ease, its two syllables slotting into bars more easily than other labels with clunkier names. Saint Laurent is a little bit of a mouthful, as is Versace and Givenchy. (However, both have spawned some of rap’s most inventive pronunciations, from Kanye self-mockingly declaring he “can’t even pronounce nothin’, pass that Ver-say-see” to 2 Chainz sneezing “Gee-Ven-Chee” before following it up with, “God bless you.”) But other than simply fitting in a linguistic sense, Gucci is an idea more than a brand in hip hop.

After all, rap is largely performative, and Gucci lends itself to that realm very well. It’s bold, opulent, capable of being highly conspicuous (a good thing in a genre which has never embraced shrinking violets). Whilst many rappers have sought to convey toughness and authenticity through their sartorial choices, leading them to humble workwear brands like Carhartt and Timberland, many others have decided that cult of personality, even at the expense of the truth, is more favourable.

This has always been the duality of hip hop, reality versus fantasy. And through it, Gucci has become a byword for a certain kind of escapism. Just as luxury brands have mastered the idea of selling us an idyllic lifestyle, so have rappers, in their own way. The designs of Michele or Tom Ford are less significant, the brand represents something more powerful as an ideal – which is why rappers like Lil Pump, only 17, continue gravitate towards or namedrop it.

In a sense, it’s a way of burnishing one’s own brand, stealing a little bit of its cultural cachet to boost your own – hip hop has always been adept of flipping traditional power structures to its advantage.