London’s queer fashion isn’t just about disco, dancing and drag, argues Rob Nowill

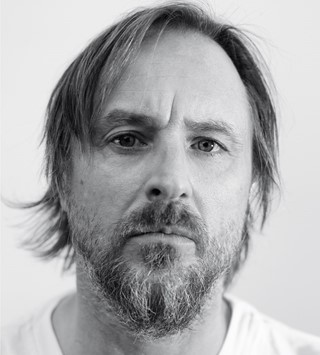

- TextRob Nowill

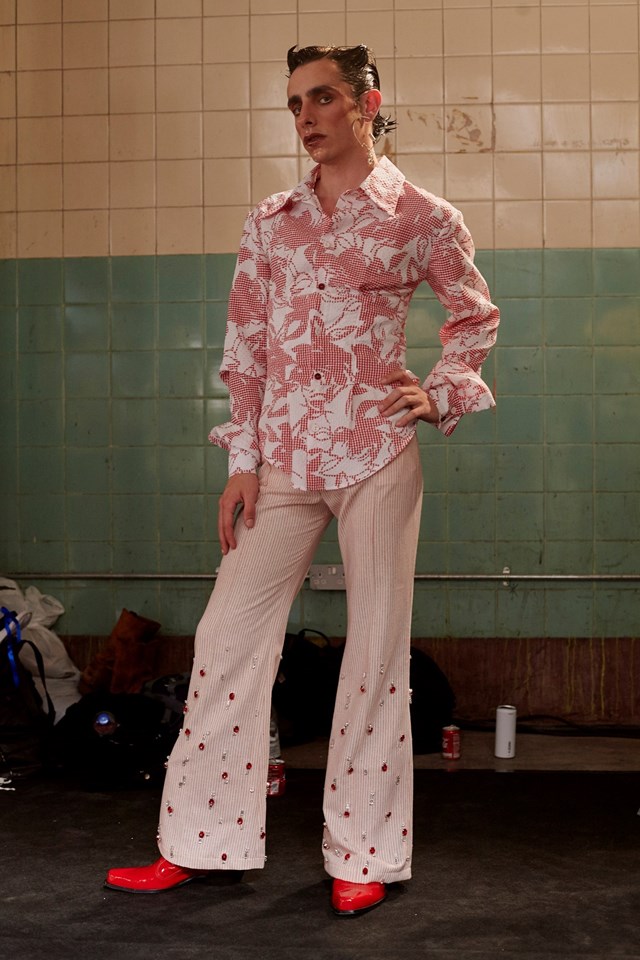

There’s a story that fashion loves to tell about queer culture. It goes something like this: gay bars and nightclubs function as hubs of creativity, where people meet, ideas are shared, and inspiration is found. This, in turn, influences the fashion designers who are a part of this world. The resulting clothes – theatrical, costumey, and exuberant – are heavily indebted by the twin poles of disco and drag. It’s an idea you’ll see parroted in any fashion magazine: only in September, the New York Times’ guide to London Fashion Week described a burgeoning “LGBTQ new wave” that’s the “talk of the town”, comprising “dancers, pink cardboard dragons, and lashings of gay couture.” And late last year, the Sunday Times Style wrote that the East London club night Loverboy would “define a generation”.

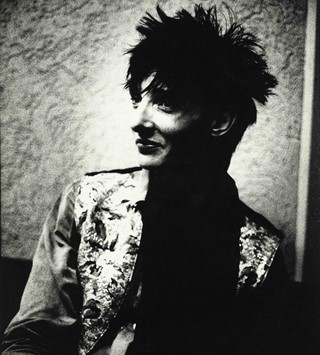

It’s a nice enough story. It fits neatly into a narrative encompassing everyone from Leigh Bowery to John Galliano to designer-of-the-moment Charles Jeffrey. And, certainly, it was once the case. In the early and mid-00s era of club nights like Boombox, Family and Nag Nag Nag, fashion and queer nightlife had become inseparable. “It was very much intertwined,” remembers Jonny Woo, the co-founder of queer venue The Glory, and a regular of the scene at that time. “I was friends with the designers, I was friends with Lulu at Fashion East, we’d walk in fashion shows…and people like [drag artist] Jeanette were a kind of muse for so many people. Everyone was fascinated by what we were doing.”

But that was over a decade ago. Things have changed.

“We’re not really going out any more,” confesses Tom Barratt, the co-founder of the design collective Art School, who staged their first runway show in June. “It’s kind of died. Online is where everything is now.” For Barratt, and his generation, inspiration and interaction are more likely to be found on Instagram than in a gay club: “I feel strangely alienated from queer culture,” he admits. “That’s what our generation is like. Nowadays it’s easier to find people you can identify with online.”

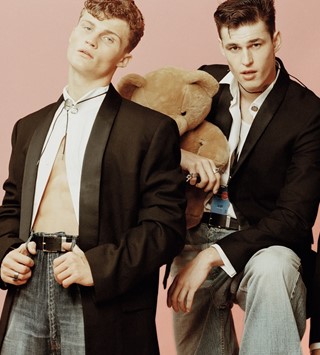

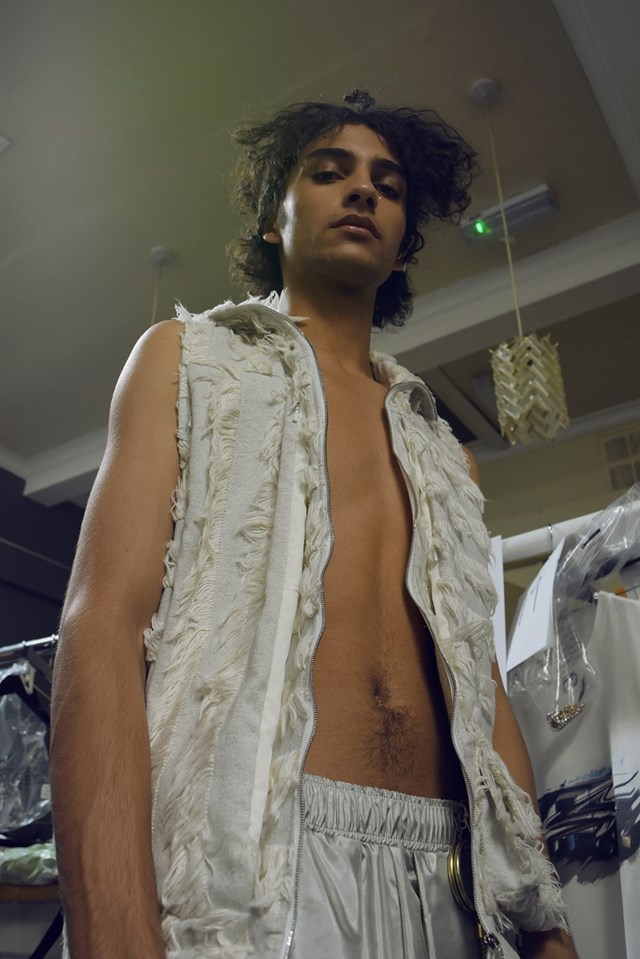

Cottweiler, the clothing label founded by Matthew Dainty and Ben Cottrell, seems to have anticipated this feeling. Their collections feel like the equivalent of a 3am trawl through the seediest corners of the internet, and are threaded with the codes of male fetishism – but you’d miss them if you don’t know what you’re looking for. This is intentional. “It’s to be discovered by the person that’s looking at it,” Cottrell tells me. Looking at the clothes, I see references to saunas, sex parties and all of the most thrillingly illicit parts of the gay experience. And I feel like a pervert for doing so – in the best possible way. It’s the modern equivalent of the bandana in the back pocket: a wink to like-minded people. And there’s something subversive about a brand that can make clothes that are redolent with gay semiotics but can still end up on the back of Kylie Jenner.

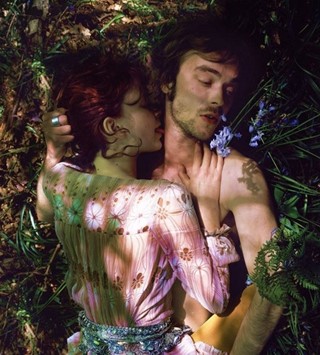

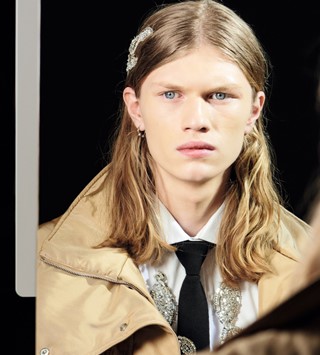

And yet, the dominant image of London’s queer fashion is still centred around disco, dancing, and drag. Are queer designers burying their heads in the sand? And, as the performance artist and clothing designer Max Allen puts it, is it really the time for “hiding behind your sequins” when the advance of gay rights feels more precarious than ever? There’s no question that the cultural conversation around non-binary gender expression is vital. And toying with the visual codes of gender still has power; J.W.Anderson’s AW13 ‘men in ruffles’ collection still feels just as impactful now as it did at the time. But shouldn’t queer fashion be more provocative and less precious than glamour and glitter cannons?

For many, drag lacks the subversive potency it once had, too – a side effect of its increasing assimilation into mainstream culture. “Drag is so tied up for young people with RuPaul, and that look, that I don’t think it’s as fashionable any more,” says Woo, a drag artist himself. “People want to escape from things that are so self-consciously styled.”

“I don’t want to do drag anymore. It’s oversaturated,” agrees Allen. “I mean, now you have queens hosting drag brunches…I feel like it doesn’t matter how subversive your act is now. You’ve become a clown.” Certainly, the impact of men wearing women’s clothing feels blunted when it’s being used in advertisements for everything from coffee to car insurance. More significantly, gay culture itself has shifted: the cultural panic surrounding hookup apps and chemsex, and the widespread closure of gay venues – alongside a rising tide of right-wing sentiment – means that many queer spaces are moving underground.

The artist Prem Sahib has been expanding the remit of gay cultural representation for the last five years. His work looks beyond the nightclub and the bar, drawing inspiration from other sites of gay interaction: the sauna, the sex club, the hookup, the HIV clinic. “I think nightclub spaces are too easily mythologised as the hub of all creativity and expression,” he tells me. “That’s not to say they aren’t influential – but it’s not just in clubs and bars where important conversations are being had.” His works feel rooted in the reality of life as a gay man, and are deeply personal. “I mediate these spaces as an individual,” he explains. “I don’t worry about accusations of glamorising because I have no shame in how I live my life.” It’s the source of the potency of his works: they feel powerful precisely because they are devoid of fantasy.

It’s an ideology that’s extending beyond art. “We aim to project ‘just do you’,” says Lee Dyer, the founder of the London/Melbourne underground night Dirty Diana (and its accompanying Instagram feed – which is so spectacularly NSFW that it’s frequently shut down). He’s noticed a shift in what people wear to the sweaty basements where his nights are held: drag and is on the decline, and the visual language of fetishism is on the up: “Leather to metal. Sweats to sadomasochistic chic. Your best mate’s footy shorts.”

Fetishism doesn’t belong to queer culture, of course – straight people have fetishes, too. And fetish has informed high fashion since Gianni Versace’s heyday, at least. But this is more than a titillating gimmick, and rather more nuanced than sticking a model in a harness. It’s an authentic expression of the gay sexual experience. “Bringing it to the club is liberating, and it encourages others to do the same,” says Dyer. And it still retains its power to provoke: the sight of a man in heels may have become less shocking to anyone living in a cosmopolitan city, but the nitty-gritty of gay sexuality is still likely to make even the most liberal of ‘allies’ uncomfortable.

The emerging label Rottingdean Bazaar also draws from a less fantastical, more bodily approach to design: they initially made headlines by making badges from their own pubic hair. But they offer more a subtle form of subversion, too. Certainly, the brand’s ‘queerness’ doesn’t jump out at you from the clothes they present, which this season included household items remade in foam. But, aside from the visual gags, they force us to confront the non-normative bodies of the people wearing them. Allen, who walked in the brand’s SS18 show, agrees: “I had foam screws all over myself but I still felt sexually powerful.” There’s something provocative about that. It feels queer.

It raises the question, though, of whether a business can be sustained by fashion designers with an explicitly queer outlook. Pieter, a menswear label founded by the Jil Sander alum Sebastiaan Groenen, quickly attracted a following from collections inspired by the reality of the modern gay experience: sweaters emblazoned with Grindr slang, prints derived from the HIV preventative PreP, collections inspired by gay ‘chillouts’. He was also a frequent collaborator of Sahib. But he ceased production earlier this year, citing issues with financing his collections. Is it sustainable to build a business selling clothes that are so resolutely detached from the heteronormative mainstream? “I guess it implies something about your lifestyle to wear these clothes,” muses Groenen. “Like we’d share almost any part of our lives on Instagram but you wouldn’t see many people publicising that they’d gone to a gay party and stayed up for three days.” So is it possible for a brand to achieve commercial impact without watering down its queerness in clichés?

New York’s designers could offer an interesting template. Shayne Oliver, the founder of Hood by Air, whose collections swiftly gained notoriety for their celebration of the queer body, has since secured a design post at the relaunched Helmut Lang, attracting critical adulation and strong support from international retailers. Meanwhile, Telfar Clemens, whose eponymous clothing line deconstructs the stereotypes of gendered garments, is this year’s winner of the Vogue/CFDA Fashion Fund. Both designers are unarguably, unavoidably queer in their outlook. But none of their work could be described as glamorous. It feels confrontational. Challenging. Cerebral. And not a sequin in sight. If anything is going to define a generation, I hope it’s this.