As Tate Modern’s new exhibition, Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, opens, we spotlight four of the movement’s most radical artists

The scholar and critic Clyde Taylor wrote in 1973 for The Black Scholar that black people in America had for once in their nearly half a millennia in America (that strange country named after a continent), begun to reject the respectability politics that had gotten them nowhere. What they got in exchange for rejecting such desperate terms of their humanity, he posited, was a true assessment of power and the brutality that kept them from it which made up the great, bookended reality of African-American life. The bookend in the 70s was the Vietnam War. As the colonial Indochine conflict became the American imperialists’ pet hobby, African-Americans became the most outspoken – and most able – dissidents to the Vietnam War by seeing their plight aligned with the Vietnamese revolutionists.

Though Muhammad Ali never actually uttered the famous line, “No Viet Cong ever called me a nigger,” millions of African-Americans did, incredulous at the fact that white Americans did not see the delusional hypocrisy of resisting integration of the lunch counters in Baltimore and Birmingham, yet appointing themselves the moral watch of the entire planet. “Black people in the 60s raised a major opposition to America’s violation of human rights,” writes Taylor. The lack of moral qualification for white Americans to lead the country, much less the world, spurred African-Americans to pursue a self-actualisation that was removed from white ideals or approximation. Black beauty pageants, media, Afros and fists went up, as did the “For Sale” signs in white neighbourhoods as soon as black families moved in. The effect of the 60s and 70s self-determining spree of blackness was, as Taylor puts it, little more than “falling short of national revolution.”

And that’s the electric edge where the Tate’s new exhibition, Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power begins. The anticipated show highlights the works of artists, active from 1963 – 1983, whose work has taken on a new urgency and new audiences. The All-Stars of the post-1968 period are present: Barkley Hendricks, Faith Ringgold, Lorraine O’Grady, Sam Gilliam and Emory Douglas. And there are the not-sung-enough heroes that also share the stage with the important works (what’s featured in the first third of a catalogue), such as Martin Puryear, whose sculpture Self is a masterpiece of the figurative imagination and the concrete abstract. The Spiral Group, a forgotten collaborative of black downtown artists, is given time, along with their most famous member/founder, Romare Bearden.

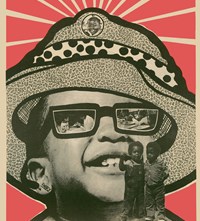

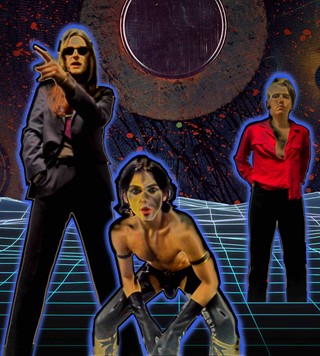

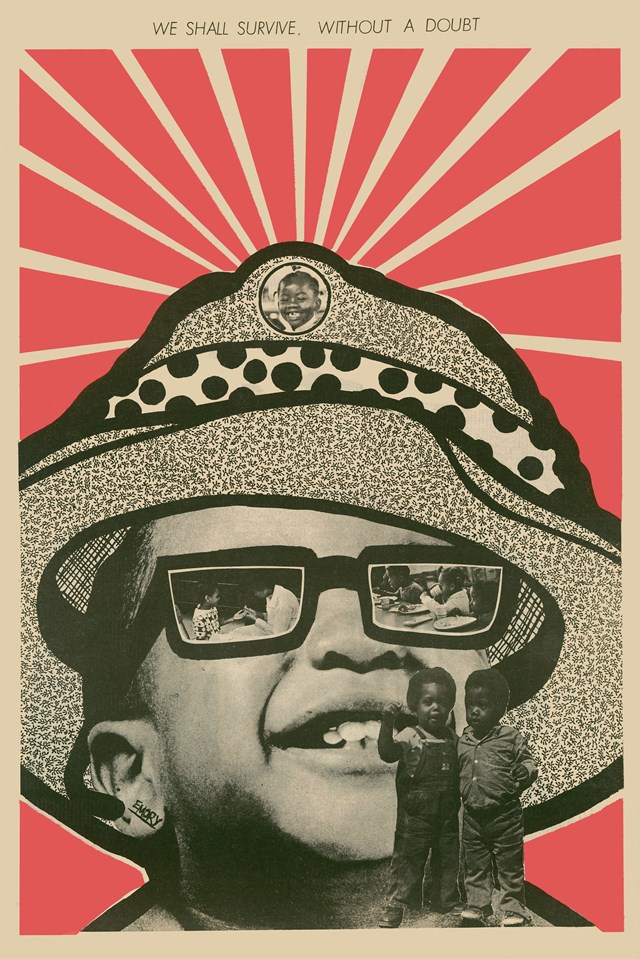

Emory Douglas

The former Minister of Culture features prominently in the catalogue and is a thematic anchor of the curated works. And how could he not be? It is his iconography, advertising and graphic imagery that set the tone of the political black art for the decade. This theory is particularly apparent when considered next to Ringgold’s 1970 poster design, All Power to The People, which could easily be mistaken for Douglas’s. Perhaps the most iconic image of his in the show is the newspaper back page of The Black Panther, which shows pigs as police. It’s a powerful allegory that has influenced black and political art for nearly half a century, most notably in hip hop and rap music, and Jean-Michel Basquiat’s painting, Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart).

Elizabeth Catlett

Renowned as a sculptress in which few examples precede her – Edmonia Lewis and Augusta Savage are the most notable American antecedents – Catlett’s work is still not championed or exhibited nearly as it should be. Her inclusion in a show is refreshing, if somewhat on the nose; Black Unity is sculpture of a raised fist in the front, and geometric African shapes in the back. But it’s also an essential piece. What is exciting about her inclusion is the show is the opportunity for her work to be discovered by a new generation.

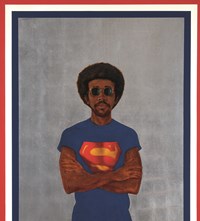

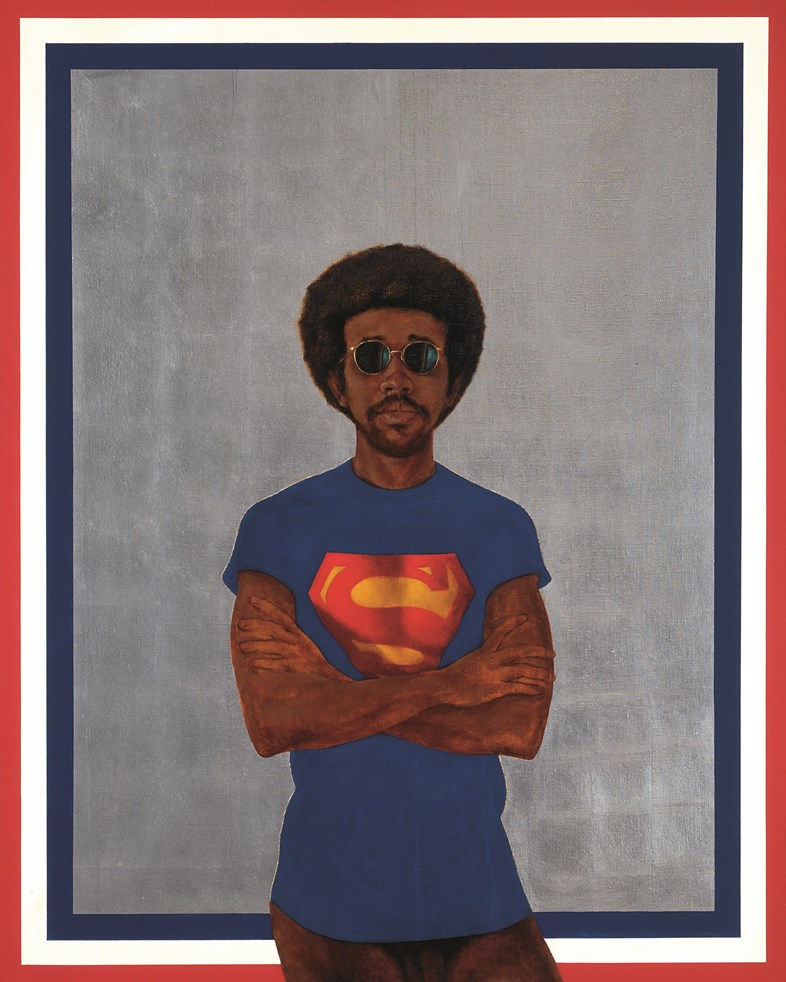

Barkley Hendricks

The painter is a bittersweet addition, having died earlier this year in April. It is his painting, Icon For My Man Superman (Superman Never Saved Any Black People – Bobby Seale), which makes the cover of the catalogue and is the “face” of the show in ads. Superman is a popular image; it’s currently in on view at the excellent show at the Studio Museum in Harlem, Regarding The Figure. Perhaps the most leonine of his peers – Hendricks proudly stands nude for a self-portrait entitled Brilliantly Endowed – the painter also is one of their most eclectic, with influences ranging from van Dyck, Marvin Gaye, medieval art and the Byzantines. His signature gold leaf conveys Hendricks’s belief in black majesty. “I want to deal with the beauty, grandeur, style of my folks. Not the misery.”

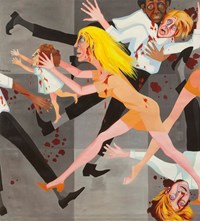

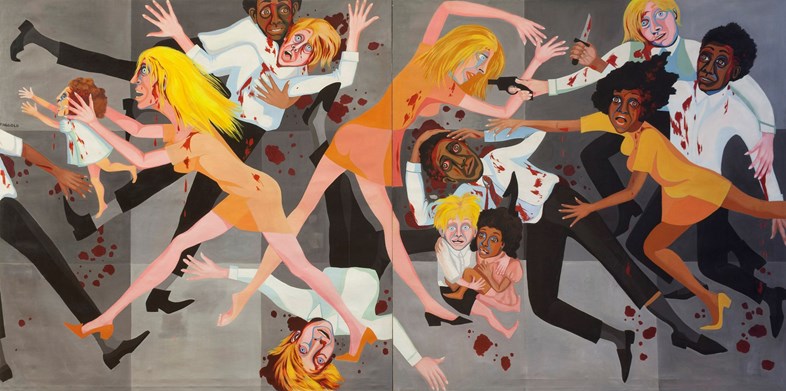

Faith Ringgold

Long famous for her quilts, Ringgold’s other oeuvre – canvases – have been the topic of conversation, particularly her American People Series, and #20, Die, which was the subject of a widely shared blog post on MoMA’s website. This painting is featured in Soul of a Nation as well. Hers is an important addition; the Black Power Movement was not without its toxic patriarchy, with often women regulated to sideline roles, erased from what in many cases they helped to found. And perhaps because of that erasure, Ringgold’s work is inherently inclusive in ways that black men’s work of that time is not. In the aforementioned piece, Power to All The People, a black woman is compositionally and emotionally the centre of gravity in the message. Because if black women and children aren’t free, black America isn’t free.

Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power is at Tate Modern until October 22, 2017.