To celebrate the V&A’s recent purchase of the Felix Dennis Oz Archive, we chart some of the cult underground publication’s most revolutionary statements

- TextDaisy Woodward

If a single publication could be said to encapsulate the spirit of 1960s and 70s counterculture, it would surely be Oz magazine – that beacon of the underground press, produced from a basement flat in Notting Hill, between 1967 and 1973, by Richard Neville and Jim Anderson, and later by legendary publishing mogul and poet Felix Dennis. The Oz story began in Sydney, where Neville and pop artist Martin Sharp had founded its lesser-known predecessor, Oz Australia, a fearlessly satirical magazine, inspired by Private Eye and the New Statesman. The duo relocated to London in 1966, where they joined forces with fellow Australian, Anderson, to found Oz London – a more revolutionary and psychedelic affair, thanks to the influence of the burgeoning hippie movement and the superior means for colour printing.

In February of 1967, the first issue was unleashed upon the world, and before long, Oz had garnered a devout readership thanks to Sharp’s eye-popping graphics, Robert Crumb’s esoteric cartoons and the editors’ proclivity for provocation. Oz’s modus operandi was to interrogate societal “norms” and infuriate the establishment. Their chosen subjects ranged from racism, gay rights and feminist theory to the environment and the Vietnam War – accompanied by a healthy dose of sex, LSD and rock music. This month, in celebration of the magazine’s 50th anniversary, the V&A have purchased the Felix Dennis Oz Archive, replete with the fascinating memorabilia the late editor acquired during his tenure. To mark the event, here we chart five of the most seminal moments from across the publication’s radical history – including the notorious issue that sparked Britain’s longest obscenity trial.

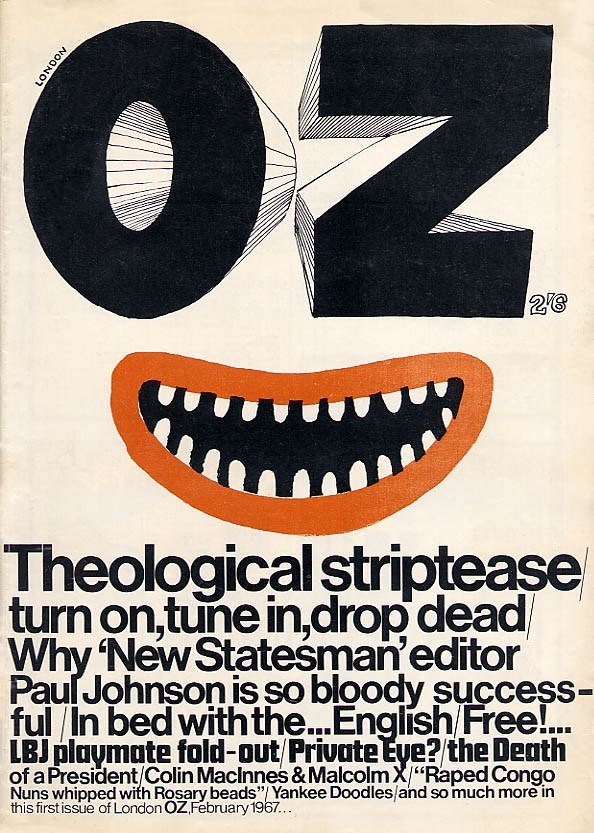

The First Issue

Oz magazine announced its arrival on the scene with a garish grin, the contents list of its first issue reading as a bold statement of intent: “Theological striptease”; “Why New Statesman editor Paul Johnson is so bloody successful”; “Colin McInnes & Malcolm X”; “Raped Congo nuns whipped with rosary beads.” From the outset Oz championed and demanded dissent: “tune in, turn on, drop, dead”.

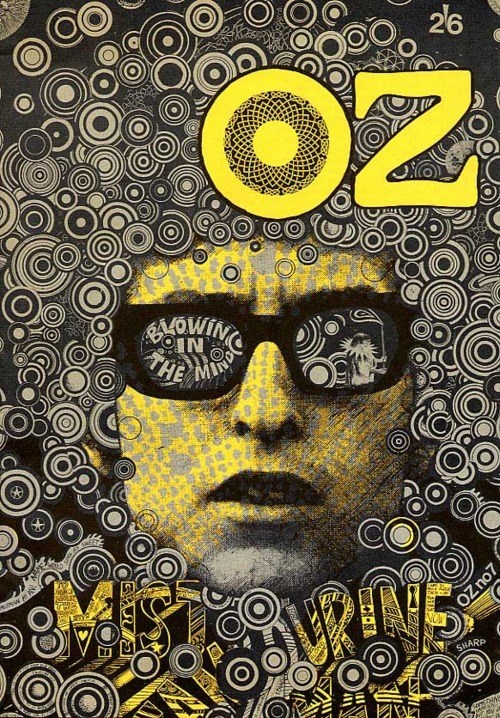

Mr Tambourine Man

“Want to know what the 60s were like?” former Oz contributor Germaine Greer once remarked. “Then look at Martin Sharp’s work.” And what speaks louder than the artist’s iconic depiction of Bob Dylan (aka Mr Tambourine Man), used to front the October 1967 issue? This homage to one of the artist’s many musical heroes embodies the psychedelic turn that Sharp’s work had taken since his arrival in London. In the reflection of the singer’s sunglasses, he inverts a single letter of Dylan’s hit Blowing in the Wind to read ‘blowing in the mind’, a pertinent manifestation of the zeitgeist. There is little doubt that Oz owed its early popularity to the compelling power of Sharp’s graphic covers.

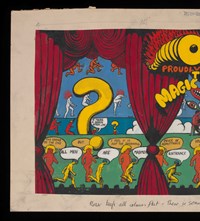

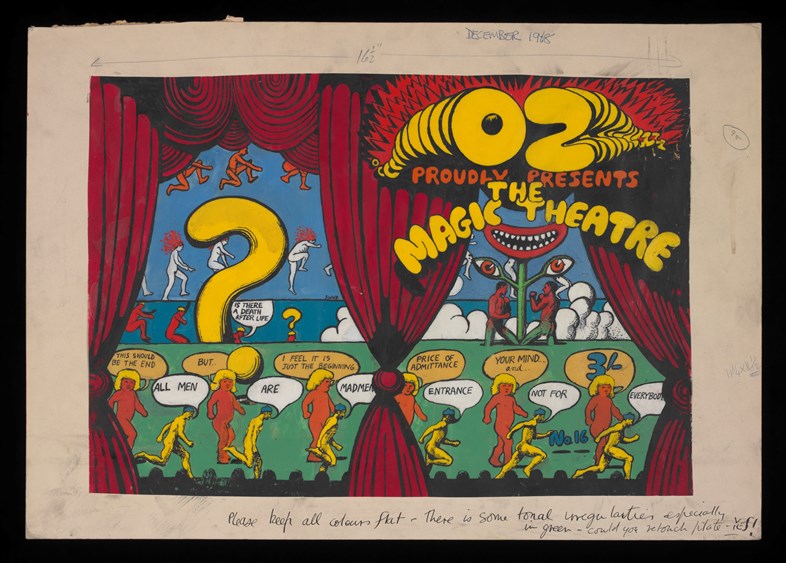

The Magic Theatre Issue

But the artist’s most revolutionary work for Oz is undoubtedly the “Magic Theatre Issue”, an all-graphic edition, which Sharp produced with film director Philippe Mora in November 1968. The 48-page issue is a multi-media melange of collage, film, happenings, light shows, theatre and photography. Suffice to say nothing like it had ever been realised in magazine form before; writer Jonathon Green describes it as “arguably the greatest achievement of the underground press”, while the magazine’s follow-up issue dubbed it “worst selling most praised Oz ever”.

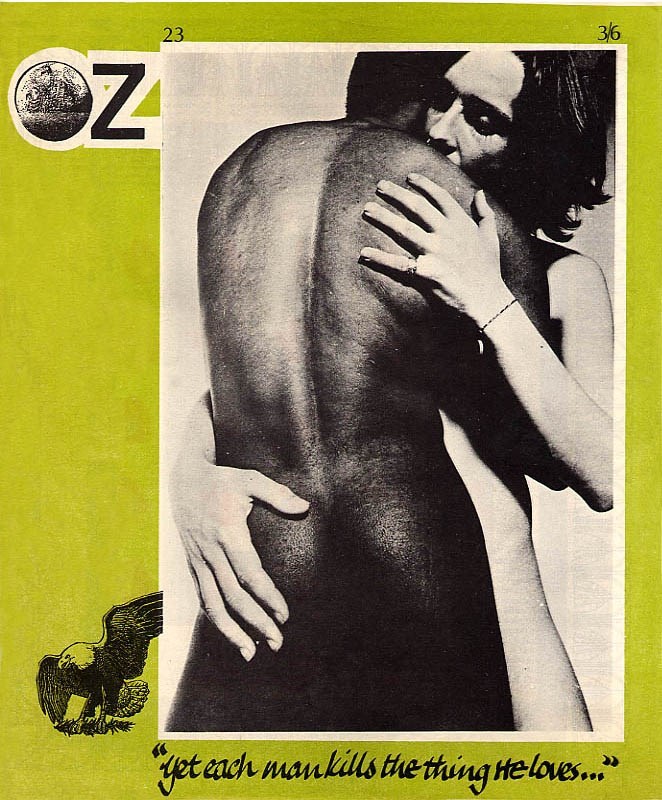

The Gay Issue

In 1969, just two years after homosexuality was decriminalised in the UK, Jim Anderson, himself gay, decreed it was time for the “Gay Issue” of Oz. He commissioned one of the magazine’s most striking covers depicting two of his friends, one black, the other white, clasped in a nude embrace, to represent the publication’s attitude towards racial and sexual liberation. Unfortunately, the Obscene Publications Squad didn’t share the same views, raiding the Oz offices upon its release. A year later, undeterred, Oz handed the reins over to an all female editorial team for the “Female Energy/Cuntpower Issue”.

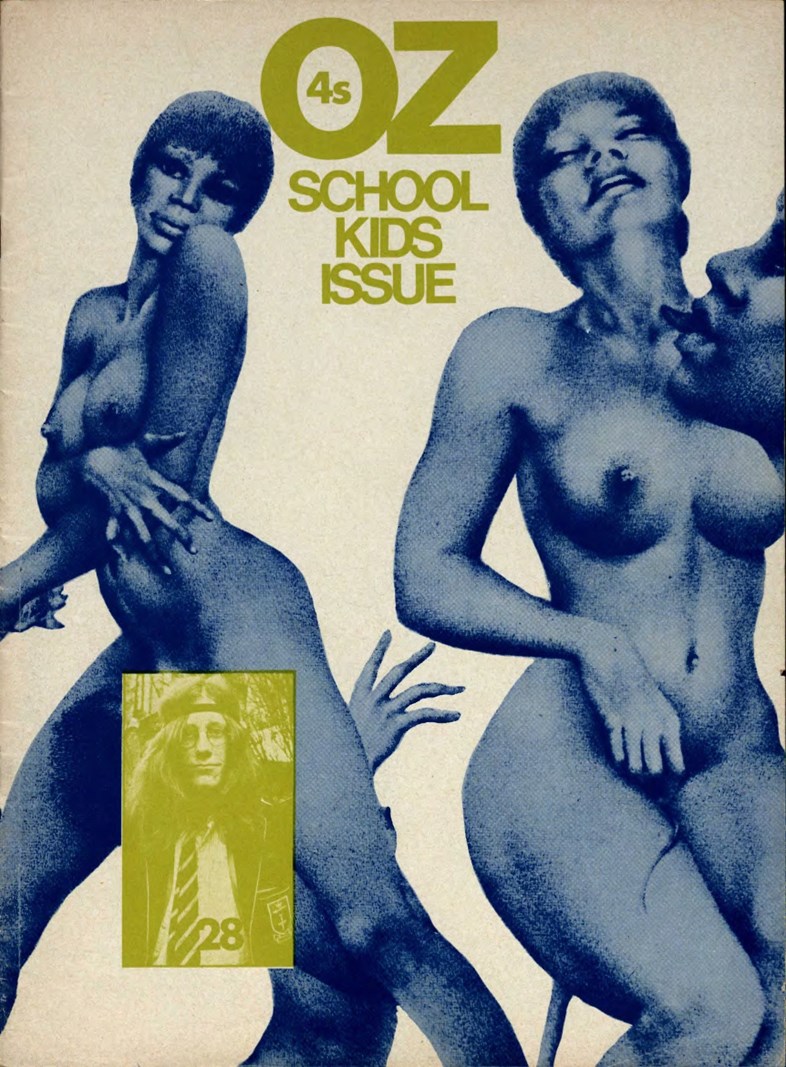

The School Kids Issue

But let’s not forget the most infamous Oz moment of all: “The School Kids Issue” of 1970. After being told that they were out of touch with their young readers, the Oz team invited a group of secondary school students to edit their May edition, which featured a sexually explicit parody of the Rupert Bear cartoon strip and a cover adorned with suggestively posed nudes. Dennis, Neville and Anderson were swiftly charged with conspiring to corrupt the morals of the young, prompting the longest obscenity trial in British history, and a huge campaign for their freedom. The trio were eventually acquitted, but not before they’d caused further outrage at their committal hearing by appearing in rented schoolgirl costumes.