Take a Trip into the Outer Reaches of the Art Universe with Bob Nickas

- TextBob Nickas

In an essay for Another Man, the curator discusses his expansive exhibition Strange Attractors: The Anthology of Interplanetary Folk Art

In 1977, NASA launched the twin Voyager space probes. Each carried with them a Golden Record, a compilation of images, scientific data, natural sounds, greetings in 55 languages, and music presenting an overview of life on Earth, which included everything from Bach played by Glenn Gould to Chuck Berry’s Johnny B. Goode. Although the folklorist Alan Lomax objected to the song as adolescent, Carl Sagan, who headed the project, defended its inclusion, insisting, “There are a lot of adolescents on the planet.” Other than a stylus, the discs came with no playback system. If one of the probes were to be discovered, and with it a Golden Disc, how do we know intelligent life would figure out how it can be played? And if the intelligent life is adolescent, might a disc more readily be used as a frisbee? Another song initially chosen, perfect for a compilation sent into space, Here Comes the Sun, by The Beatles, was left off the disc. The group had enthusiastically agreed, but their record company, EMI, which held the copyright, refused. We can only wonder: did it occur to anyone to replace it with Nina Simone’s interpretation? Would it have mattered that she was black and a woman? Or was her balancing act, infusing hope with sadness, simply too human?

Music accounts for about three-quarters of the disc’s contents. There is no visual art. Are artists somehow too alien, of the Earth but extraterrestrial? Why was art set aside in favour of various recordings – the sound of a kiss, of a whale and ocean waves, a message from Sagan’s young son? (“Hello from the children of planet Earth.”) Art from the caves in Altamira, Lascaux and Chauvet would have communicated as much, if not more. This was the beginning of art, of humans representing themselves in the world, a new level of consciousness.

Artworks may be thought of as ‘strange attractors’, drawing us towards them, while also being attracted to and possibly summoning one another. There is an interconnectedness across distant points in time and space that is undeniable. The very idea of the contemporary as it persists within the art world is meant, in some measure, to deny art’s connection to the larger realm; to ritual and folk-magic, to pre-history itself, insisting as it does – for some inconveniently – that meaning inhabits objects and images, that it may be sensed, is alive inside them, and when it’s not, that absence is palpably felt. At its most resonant, as art vibrates, in the words of conceptualist Lee Lozano, quantum-mechanically, its structure and behaviour visible on an almost molecular level, art doesn’t necessarily require translation, and not in more than 50 languages. Why is it that all children, and from an early age, draw? There is a need that’s universal, and it may include the universe.

With all this in mind, I organised an exhibition in Los Angeles in 2017, on the 40th anniversary of NASA’s Voyager and the Golden Disc, intended as the first in a series. Other shows were meant to follow, and to date a second one has. With its terrestrial launch pad, Strange Attractors: The Anthology of Interplanetary Folk Art was subtitled Life on Earth. The Voyager probes, having travelled beyond the rings and moon of Saturn, are expected to continue their mission in interstellar space for another seven years, until about 2025, at which time nearly half a century will have passed.

These are the oldest manmade objects sent furthest from the Earth, and have now entered into the realm of mythology, not only for their mission, which continues, but as the ultimate ‘message in a bottle’, a record of life on our planet – with the exception of art. A show comprised of contemporary artworks, proposing them as ‘interplanetary folk art’, questions our notion of the term. Is everything new to be automatically considered contemporary? The very designation represents an interminable holding pattern into which art continues to be placed. Of one thing we can be sure: artworks are themselves space probes. To understand them in this way is, on the one hand, to test our tolerance for what may be accepted as a work of art, while on the other to absolutely marvel at art’s heightened capacity to retrieve, translate, and transmit information beyond itself, far beyond the moment in which it was made. Works of art may be thought to store data for future retrieval, to aid us in understanding what came before and to help us navigate what’s to come. In this we envision a reciprocal elasticity. Time moves in more than one direction. Hasn’t it always?

Taking a cue from the music and audio selection on the Golden Disc, the LA exhibition included a playlist/soundtrack assembled in collaboration with the artist Dave Muller. Playing continuously in the office area adjacent to the gallery, it was also available on its website. For the exhibition’s second volume, held this past autumn in New York at Kerry Schuss Gallery, music came to the fore in the show’s subtitle, The Rings of Saturn. The exhibition was based on an expanded notion of field recordings in both music and art. Made outside of a professional studio, field recordings are captured on site, often in nature or in the lived environment of the performers, where there is a resonant overlay: the music of everyday sound, the discovery of which opens up to a sense of rhythm and the pulse of our own bodies. Recordings made in the field are in this sense alive. In terms of visual art, the post-studio artists of the later 60s were also working in the field, whether with permanence, creating earthworks such as Robert Smithson’s iconic Spiral Jetty, or ephemerally, as in Allan Kaprow’s Fluids, for which an ice block structure is built and eventually melts. In the mid-to-late 80s, related, though more modest gestures, were made by artists such as Mark Dion and Laurie Parsons, whose practice – poetics and anthropology intermingled – might be termed an anthropoetics. Today, something similar continues, often within a stone’s throw of the studio, in the street, on the urban beach, and relates to an alchemy of recycling, to the vernacular re-imagined – the potentiality of everyday objects, particularly castoffs and trash, and their transformation.

In The Rings of Saturn, an unexpected inclusion of works that engage opticality suggested Op as an art engaged with vibration that is audibly visible, with looking/listening in parallel: the artwork as performer, the visual elements as a coming together considered acoustic in their overtones. Here, volume also amplified levels of sound and expansive patterns, from rain rhythmically falling into concentric rings within puddles at our feet while reflecting the sky above, as in a Paul Lee video, to the silent uncorking of a champagne bottle by way of Kayode Ojo’s humorous fetish, Molotov: revolution as celebratory. To expand our sense of field recordings and make explicit the echoes between visual and sonic realms, a horizontal loop of album covers ran around the gallery, artworks hung above, below and within this line, intermixed, sound-on-sound: Alice Coltrane, Mike Cooper (the experimental British guitarist who has travelled the South Seas), Fred Frith, Milford Graves and Don Pullen, Emahoy Tsegué-Mariam Guèbru (ethereal piano compositions from the Ethiopian nun), Yumi Kagura (a Japanese temple), Norberto Lobo (an Amazon mindscape), Angus MacLise (original drummer for Velvet Underground, an occultist who died in Nepal), Nurse With Wound, Terry Riley (Descending Moonshine Dervishes), Mustapha Skandrani (the Algerian pianist), Leslie Winer, La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela. Interspersed among them: Mushroom Ceremony of the Mazatec Indians of Mexico, Music From Mato Grosso Brazil, Music From Saharan Cellphones, Sounds of Insects, Sounds of the Junkyard, and Maya Deren’s late 40s recordings of Voodoo rituals in Haiti. From this loop, the exhibition’s inverse event horizon, there were points of further return: an eight-hour playlist/soundtrack, again compiled in collaboration with Dave Muller.

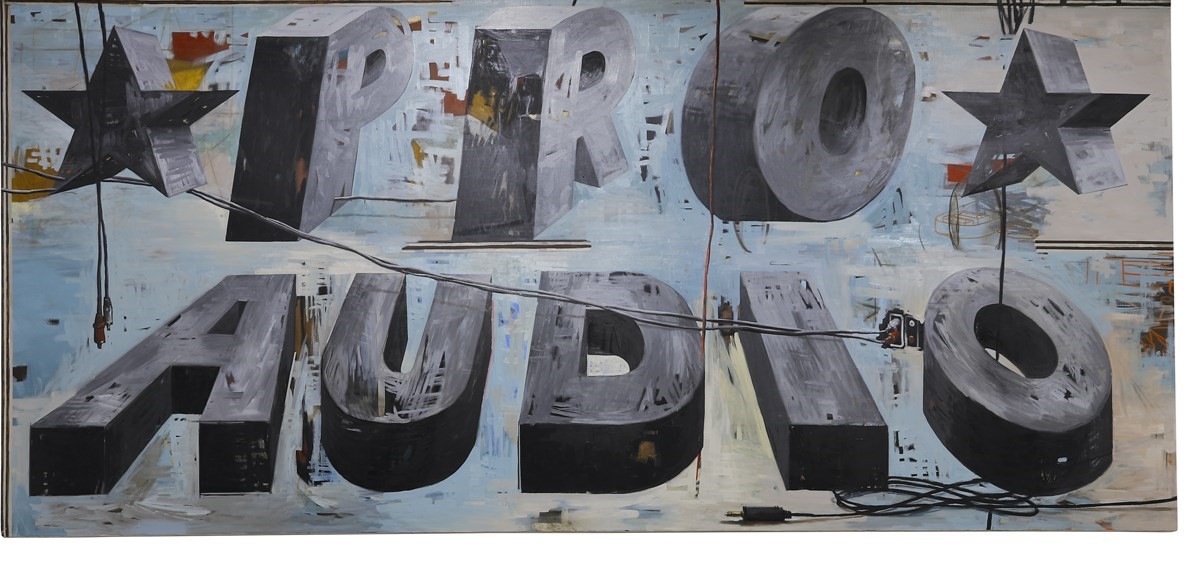

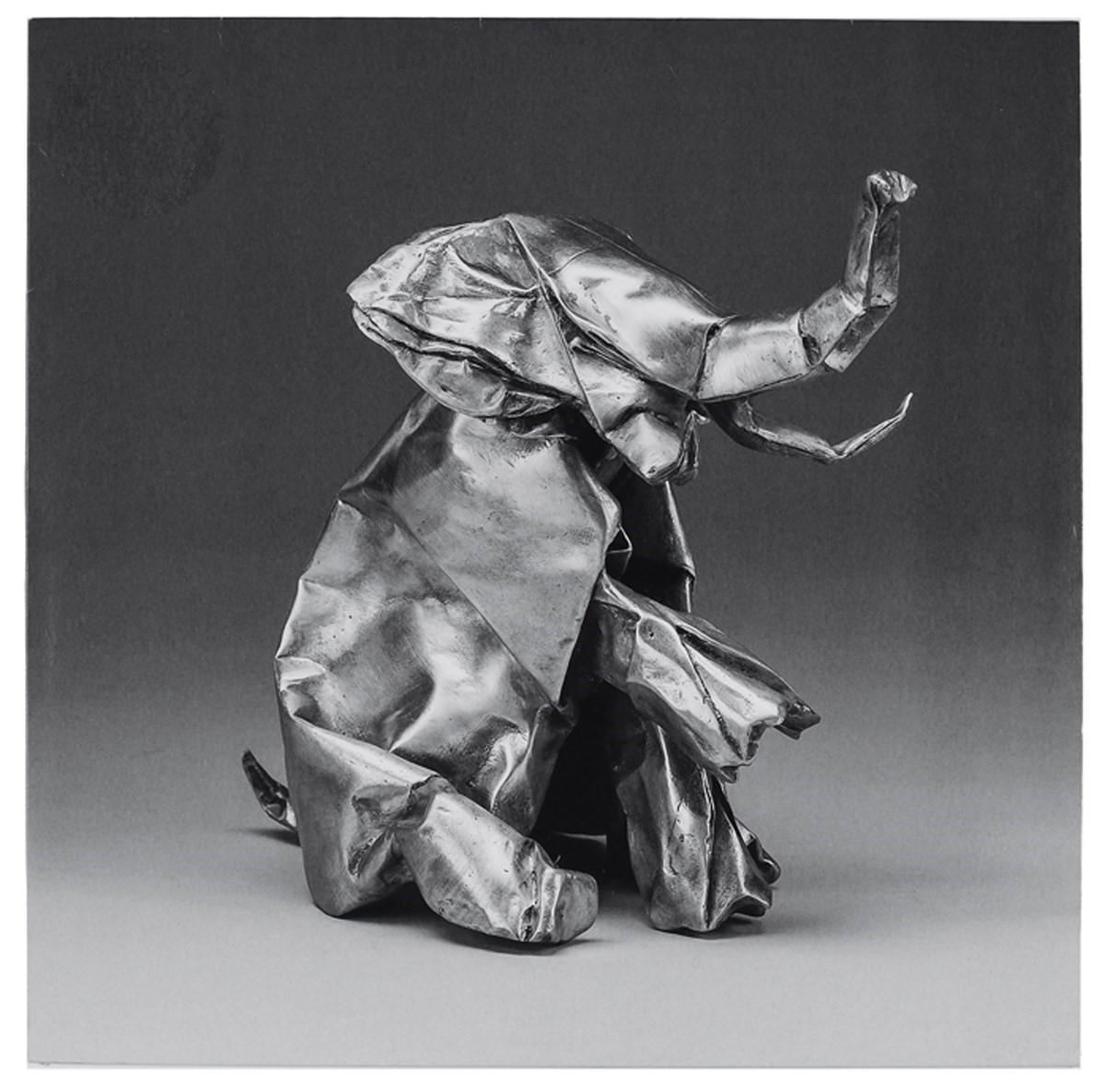

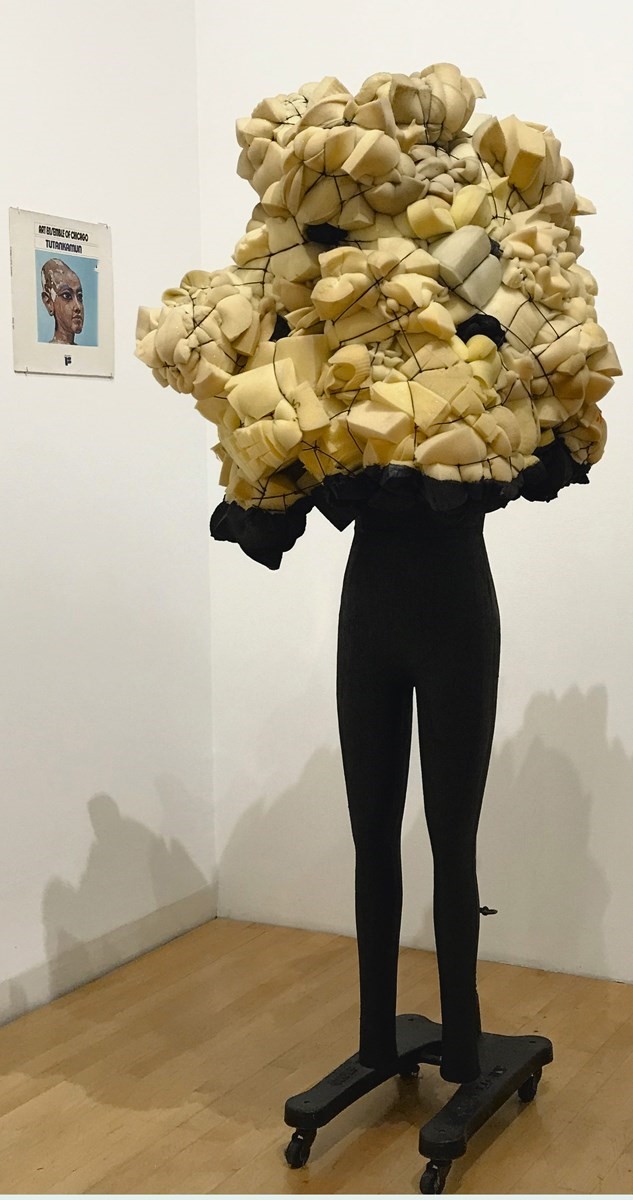

Looping and refraction were present symbolically and materially in artworks tuned in to various frequencies: the snake coiled at the centre of Swedish artist Moki Cherry’s vibrant banner, spiralling outward, flowered horns facing north, south, east and west, which had been hung on stage at concerts by the omni-directional Don Cherry; roto-reliefs turning and snakes entwined in Philip Taaffe’s Emblem Painting; the reflective silver skin of Steven Stapleton’s Spiral Insana; a small phase of the Moon painted on mirror by Lisa Beck; German conceptual artist Hanne Darboven’s record, Der Mond ist Aufgegangen – The Moon is Risen; Mamie Holst’s radiant Landscape Before Dying, a distress signal, perhaps unheard, in deep space; Tillman Kaiser’s photogram, seeming to emit electricity and radio waves – intercepted by the Dan Walsh sculpture, Receiver. Interwoven lines of vibrant colour knitting, Chip Hughes’ painting evoked a synesthetic speaker from which musical patterns chromatically emerged. Beyond the metaphorical, there were images of sound and its absence: such as Nancy Shaver’s sculpture, Trombone Missing; the silenced and restrained figure embodied in James Crosby’s Use Bound in a Sentence; the waterfall in the Lukas Geronimas photo; the tea kettle about to whistle in Nikholis Planck’s waxy Kettle Study; the delicate wind chimes hung from Jutta Koether’s nocturne; Mitchell Algus’s surrealist tower of shells, on a pedestal next to the record Sounds of the Sea; the body-operating of Aura Rosenberg’s psychedelic mandala, Golden Age Rorschach; the ten-part vocal score Jane Benson composed from all the chapters of WG Sebald’s book, The Rings of Saturn. With its tangled wires, plugs and speaker-type letters, Sally Ross’s Pro Audio loomed above the room, while the monkey gazing up at it from Josh Tonsfeldt’s photograph, Elephenta Island, seemed to hear something we can’t.

Down below, directly connected to the notion of field recording, were works made from things scavenged in the street, as well as scenes recorded on various forays beyond the studio, from Yuji Agematsu, a master of found object-poetics; the New York-based Ugandan sculptor Leilah Babirye; Tony Conrad (PVC trumpet!); Ryan Foerster, and the hallucinatory wonder revealed by his half-broken camera, spirit photography for our time; visionary artist/musician Lonnie Holley and his protester/lawn jockey; Candy Jernigan (the drug paraphernalia of Found Dope, collected on East Village streets in hairier days gone by); the magic potions of Lazaros (each their own encoded ‘message in a bottle’); and B Wurtz, who has conjured art from next to nothing, since the early 70s. The only work with a mechanical apparatus, Tonsfeldt’s otherworldly liquid projection within a television laid bare, was brought down to earth: a haunted cradle containing grape stems, a child’s sock and an insect skeleton. These elements served as a reminder of the fragility of humans and the natural world. Despite the artist’s tinkering, the flatscreen still functioned. In an ongoing age of machines, there is a certain stubborn persistence that they, and we, share.

Recently, Voyager 2, despite its creaky 70s engineering, has travelled beyond our heliosphere after more than 40 years, 11 billion miles from Earth, continuing on to interstellar space. Remarking on the achievement, Suzanne Dodd, the Voyager project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, was compelled to put it into perspective: “You can think of what the technology was. Your smartphone has 200,000 times more memory than the Voyager spacecrafts have.” Let’s not forget that in times as troubled as those that have come before, with the very existence of the planet in peril for future generations.

The naming of one work in Strange Attractors rang clearly, a drawing of multiple interlocking Saturns by Richard Tinkler, for which the artist quoted the mid-19th-century French historian Jules Michelet, as a warning and with resolve: Each Epoch Dreams the One to Follow.

This article appears in the S/S19 issue of Another Man.