Remembering Merce Cunningham Through Stories of Those Who Knew With Him

- TextHolly Connolly

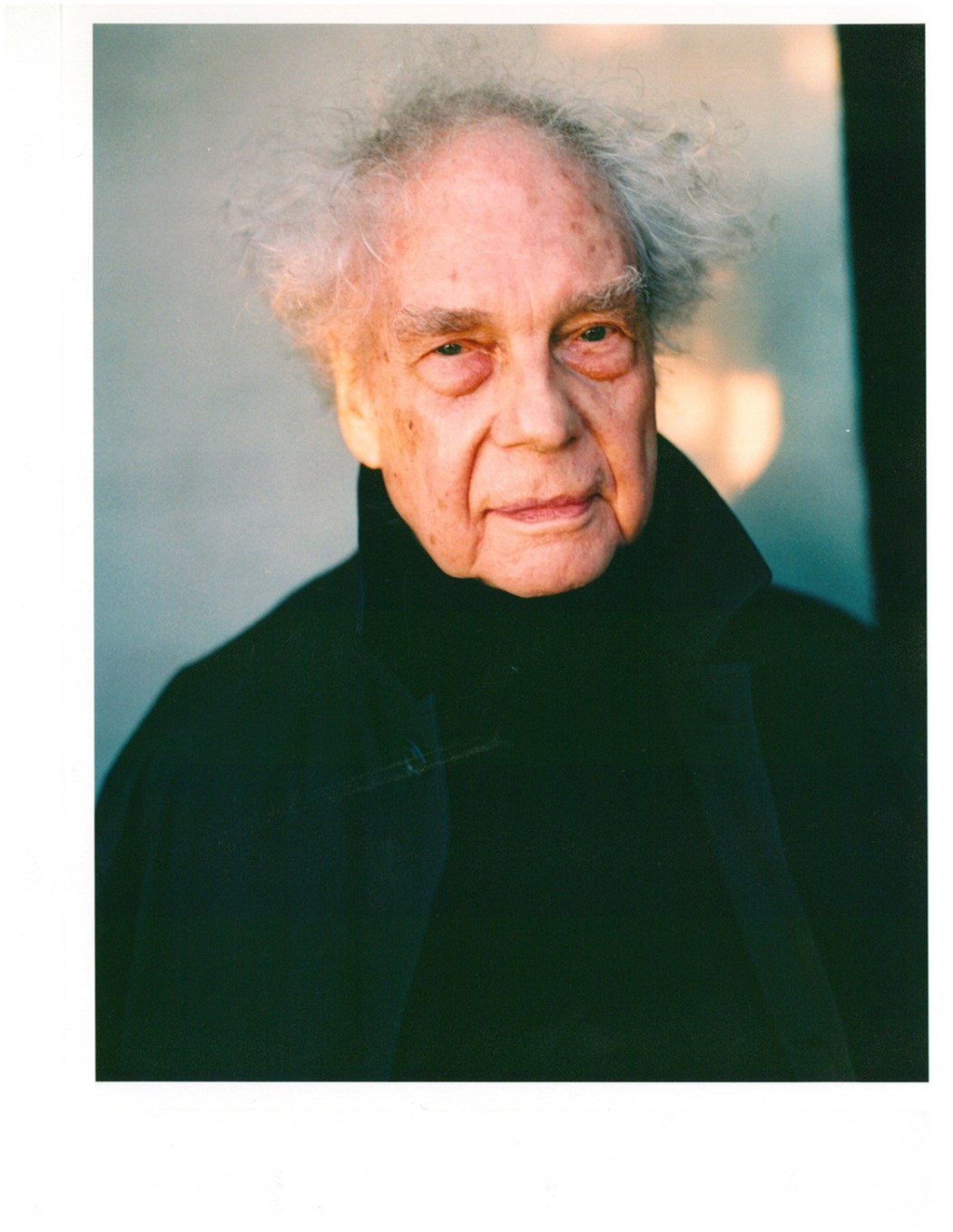

To celebrate 100 years since the birth of Merce Cunningham, five people share their memories of one of the most influential American choreographers of the 20th century

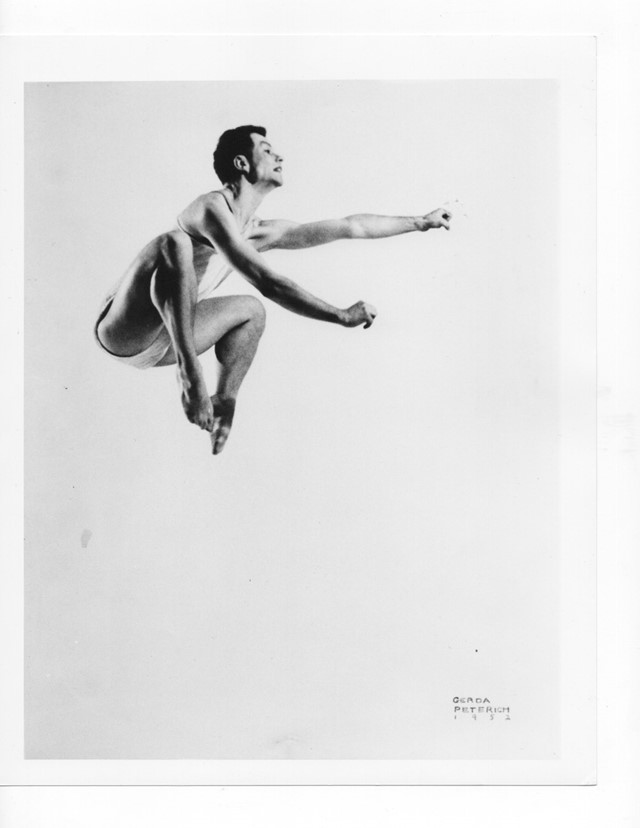

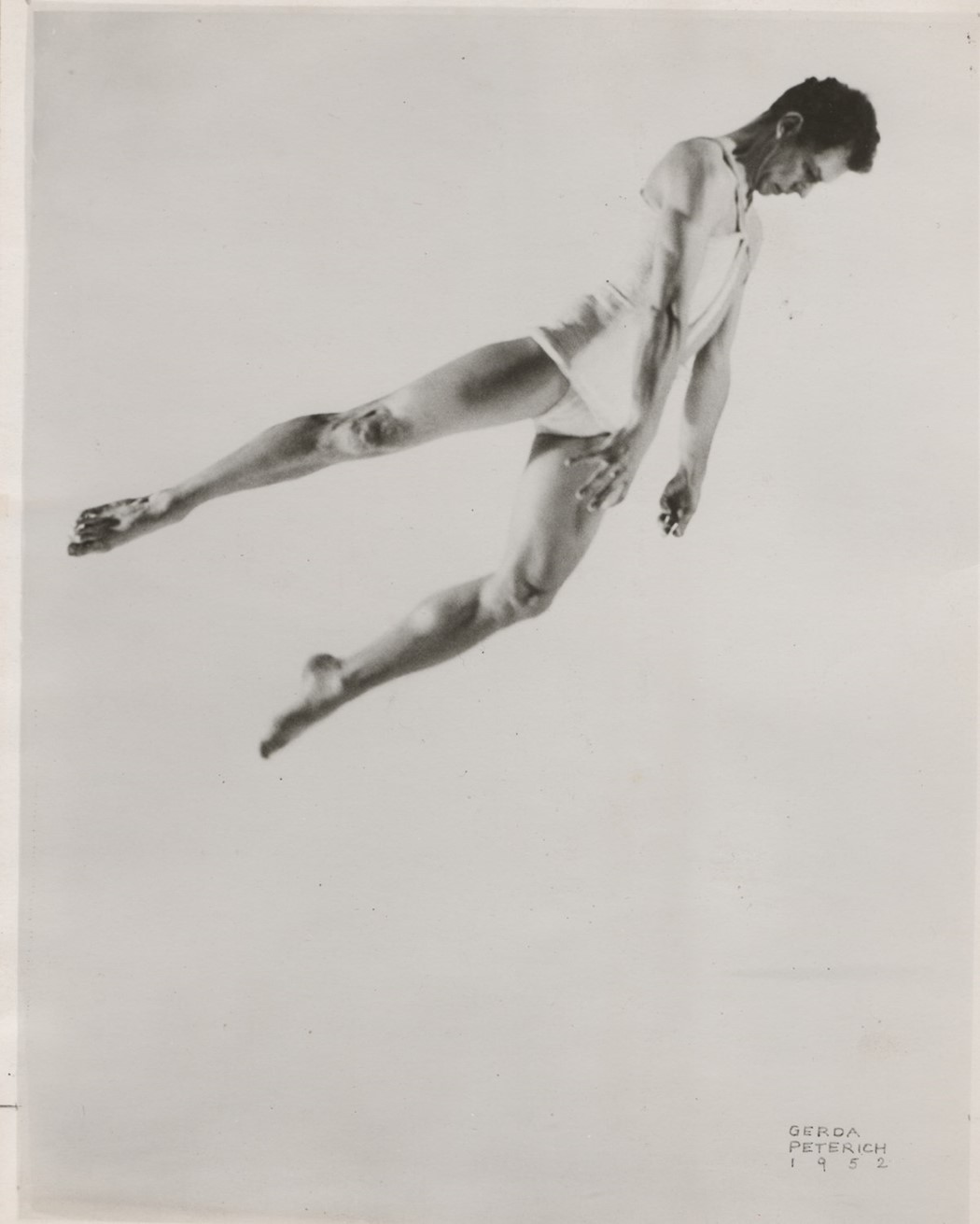

Scouted by Martha Graham aged 20, Merce Cunningham would go on to become one of the most seminal and transcendent choreographers of the last century. Founding his eponymous dance company in 1953, with his life partner and frequent collaborator John Cage, he had a conviction in movement and in dance as an art form in its own right which has shaped contemporary performance.

Cunningham’s openness to working with other artists across disciplines meant that he stayed at the vanguard of culture through his lifetime. Robert Rauschenberg, who he met at the experimental Black Mountain College in the early 50s, was a longtime collaborator, creating sets for his company for over a decade, and Andy Warhol’s now-iconic Silver Clouds appeared in RainForest in 1968. In 1997 Rei Kawakubo created the costumes and stage design for Scenario, drawing heavily on her notorious Body Meets Dress, Dress Meets Body collection of the same year.

This commitment to the new manifested as a love of technology too. He began making films with the video artist Charles Atlas, and by the 90s he was experimenting with the computer program Life Forms and creating works that responded to, and incorporated, computer technology. Though these weren’t always completely successful, as the Walker Arts Centre curator Joan Rothfuss put it in conversation with AnOther, “Wouldn’t you rather see an ambitious failure than a safe success?”

As the Barbican celebrates his centenary, we spoke to those who worked with him for their memories of Cunningham.

Siobhan Davies

Siobhan Davies began performing with the London Contemporary Dance Theatre in 1969 and went on to become their resident choreographer before founding her own company, Siobhan Davies Dance, in the late 80s. She was one of the dancers selected to appear in Night of 100 Solos.

“The first time I met Merce, Richard Alston and I, we would have been in our very early 20s, and we’d gone to Fondation Maeght, in Provence, to see his company perform. One day he and John Cage came to eat in the hotel where we were staying, and the patron told them, ‘There’s a young couple outside,’ (we were not a couple!) ‘who have come from London to see your work, and I think they would love you to speak to them.’ Now normally in those circumstances, most people would go, ‘Well that’s very nice, but no thank you!’ But no, they both came out and spoke to us.

“I worked in his studios for over a year, and then over the years he came to see what I was doing, and I suppose we just built up, very slowly, some sort of connective tissue.

“He was super clear, I think sometimes he was quite impatient, which made all of the class be kind of alert. My understanding of that is that he much preferred making dances than teaching dancing. Later, when I had more conversations with him I think he did indicate that what he really liked was making; he could make every day of his life. Which was wonderful for me to hear, and obviously quite rare for choreographers to be able to do, but I think he could.

“His studio was full of other people. Meredith Monk would come and sing during class, you knew that there were visual artists there preparing for the rehearsals, or doing whatever they were doing. So you were in the presence of what Merce and John were making, which was this situation of many people, a real creative questioning energy.”

Daniel Squires

Daniel Squires spent 11 years as a dancer in the Merce Cunningham Dance Company through from the mid 90s onwards, and a further five staging projects for the foundation and the Cunningham Trust. He did the staging of Night of 100 Solos.

“The first actual conversation I had with him was at a party, I think it was on Christmas Eve actually, at the end of 1995. I remember sitting and talking to him at one point, and he was talking about leaving the Graham Company and starting to do his own thing, and how his experience there influenced what he wanted to do. And he was classically Merce, simple understatement of, ‘Oh, well they started sitting down so I thought, well we’ll start standing up.’

“We would rehearse in silence, and I mean really silent. It wasn’t just there wasn’t music on, you’d run a 45-minute piece and nobody would say a word. That was somehow simultaneously vulnerable, and at the same time enabled you to develop very strong and genuine connections to what you were doing, and understand what everybody else was doing. Because there was nothing to, not only was there nothing to support it, but there was nothing to hide behind; you couldn’t be anything other than genuine.

“He was so interested in finding, creating strategies to open up new ways of thinking for himself. I don’t think he was trying to be groundbreaking in a global sense or an art historical sense, I think he was just trying to break open his own preconceptions. One big impact that’s had on me is not to put any emphasis on trying to make something that changes the world or changes art or changes anything, but just to simply do something that’s a little bit unknown to myself, and might also be unknown to others, and therefore might open up something for them.”

Carol Teitelbaum

Carol Teitelbaum was a member of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company between 1986 and 1993, and the faculty chair of the Merce Cunningham School from 1998 until its closure in 2012.

“I had been in other situations in which the choreographer or director made personal, disapproving comments or became unproductively emotional. This was never the case with Merce. It’s not that he didn’t have opinions about people, but he did not speak directly about such matters. In rehearsal he understood that he and his dancers were looking to find a way to make what he was asking for possible. But boy did you want to please him, and you often didn’t know if you had.

“Merce’s interactions with his dancers changed over the years. During my time as a dancer, the exchanges were cordial but fairly limited. Many years later, when I was overseeing a rehearsal at Westbeth, a phone was brought in for Merce to speak with his dancers, who were on tour and warming up before a show. I was fairly shocked to realise the phone was being passed from one person to another to have their own chat with Merce; he felt grandfatherly towards those dancers and could show it.

“Teaching the Cunningham technique, it’s always a great privilege to share the idea that when a dancer brings their full physicality and full self to the task of dancing, without needing to add anything or give the appearance of anything, there is drama enough. A human thinking, feeling and moving fully is all the drama in the world.”

Silas Riener

Silas Riener was a member of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company from 2007 until its closure at the end of 2011. Since 2010 he has often worked in collaboration with Rashaun Mitchell, a fellow former dancer at the company. He was involved in L.A.’s Night of 100 Solos.

“Merce had a way of making you want to work as hard as possible in every moment, and he did this without a lot of vitriol, it was just enough that he was watching. He would watch performances from the downstage right side wing and I could always feel his eyes on me.

“In the studio he could make the movements that we did all the time new and exciting. He sometimes would say very little, but what he did say was filled with importance. I felt like he was always delighted by movement and its possibilities.

“Merce’s legacy could be the altering of perception and choice in what a dance performance can be, should be, has to be, has to mean, has to look like. He took a form and conventions and began to question them, to change them. It’s paved the way for every artist coming after him to be different, to be radical.”

Michael Cole

Michael Cole was a member of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company between 1989 and 1998. He was inspired by Cunningham’s use of computer animation in 1993’s CRWDSPCR to create his own animated dances, eventually becoming a motion graphics designer.

“I’d gone to New York to take a class with my idol, Paul Taylor, but when I arrived at the studio, I was told me there were no classes at the Taylor studio but that I should take class chez Cunningham. When I arrived at the street, unable to locate the entrance, I spun around and saw Merce Cunningham himself, carrying a grocery bag filled with cat food and tea. I said, ‘You’re Merce Cunningham!’ He said, ‘Yes I am.’ I asked if there was a class I could take and he said, ‘Let’s find out.’

“Merce had the reputation of being cold or at the very least, aloof. For me this was exactly what I needed at first. The most glorious times working with him were in the creation of a new dance. There might be two dances in a row that tackled similar choreographic issues and then out of nowhere in the next work he would transport you, dancer and audience alike, to a different planet.

“In the piece Beach Birds I have a long solo where I stand on one leg and slowly wave my arms like a bird in flight. When Merce first gave me the part, I was so nervous I doubt I stayed there for a full minute. After every performance of it I would exit stage right, where he typically watched the entire show, and quite often he would grab my arm and softly say, ‘Good. Now stay a little longer.’ Merce didn’t berate me, instead he gently pulled something out of me that he knew existed, even if I didn’t.”