Remembering Bruce Chatwin, the Greatest Travel Writer That Ever Lived

- PhotographyChrista Leonard

- TextJames Fox

Bruce Chatwin was a restless soul and a charming chatterbox, forever fuelled by curiosity and irreverence. Here, his friend and former colleague James Fox remembers the man and his words...

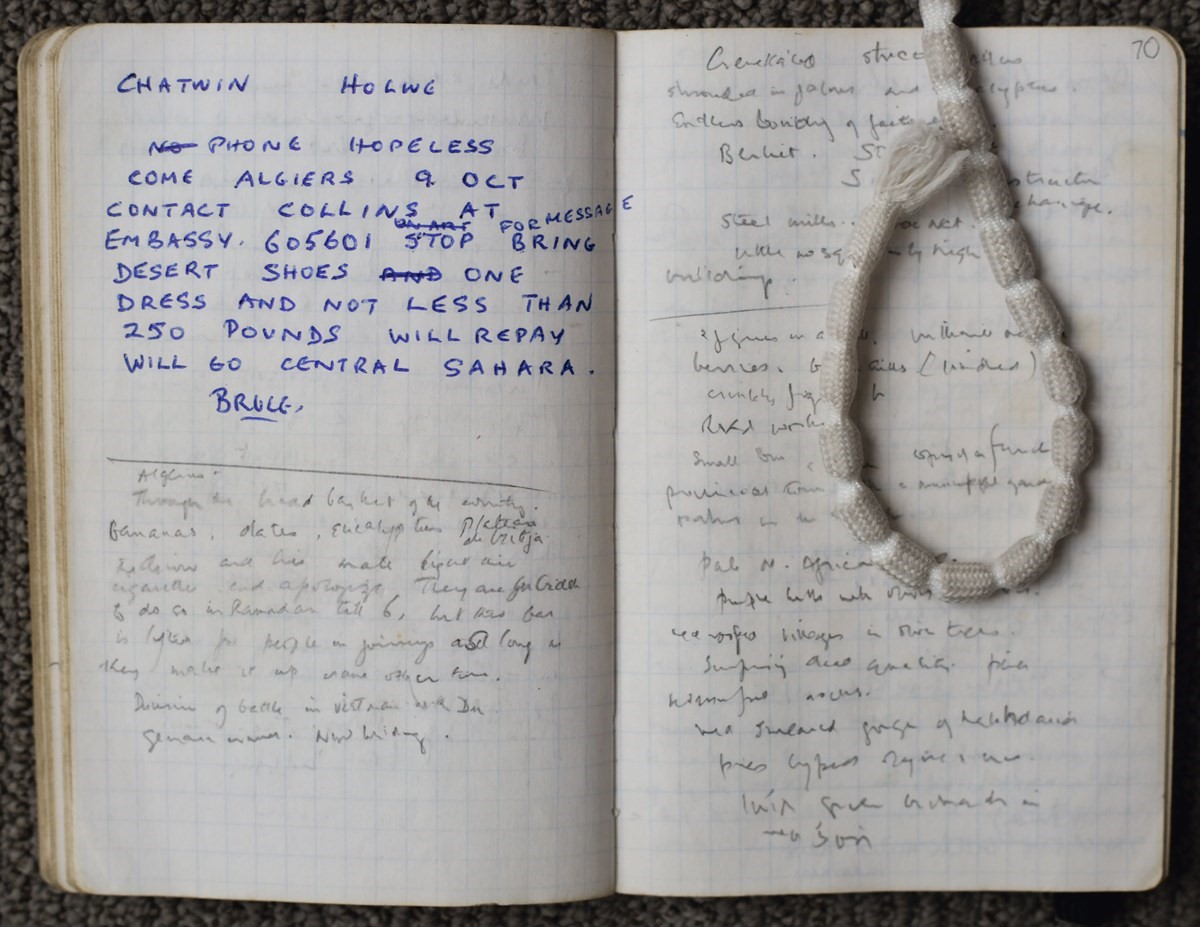

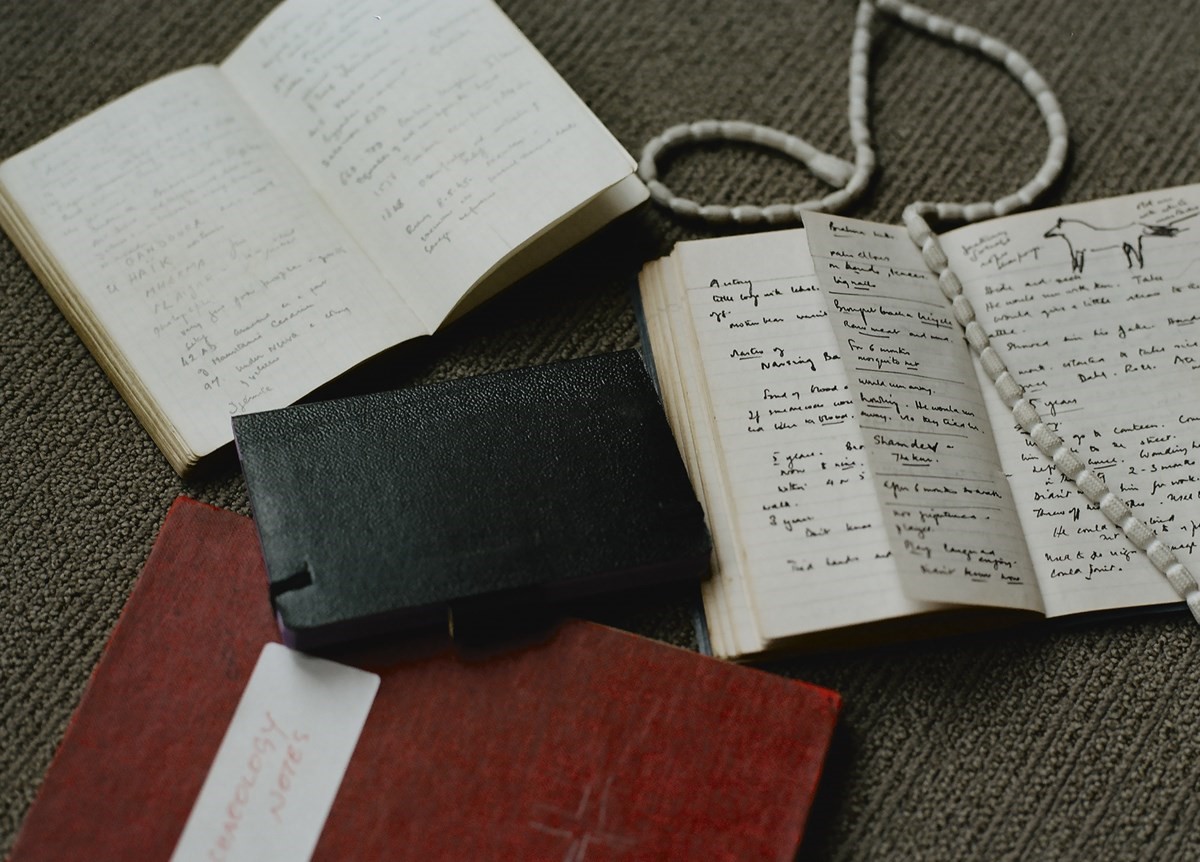

Bruce Chatwin began to be published when he was 30; he died at 48. The Bodleian collection gives some idea of his phenomenal output in that period, when he seemed barely to have had time to learn his craft or develop his unique gifts. It was at the Sunday Times Magazine, in the early 70s in its heyday of high talent and world-famous photojournalism, that Bruce became a writer, quite suddenly and almost by chance. For me it is his journalism – some of the first pieces he wrote then – that is his most original and exciting work. I worked on the magazine then, watched his debut at close quarters and became friends with Bruce – as much as one ever could become friends with this brilliant, intense, laughing, fast-talking, energised blue-eyed performer, who barely sat still for a second, except to write. Restlessness was his theme, almost his life’s work: restlessness as the natural human state. ‘In one of his gloomier moments,’ he wrote, ‘Pascal said that all man’s unhappiness stemmed from a single cause, his inability to remain quietly in a single room.’ He had left Sotheby’s, which he called ‘Smoothieboys’, where he had been a precocious head of the Impressionist department in his 20s, to write a great, failing book on Nomadism and restlessness (eventually The Songlines). It had nearly bankrupted him by the time Francis Wyndham, writer, editor, literary mentor to many, offered him the job of art editor on the magazine. Soon Wyndham suggested that Bruce himself write some of the pieces he was commissioning.

The ‘colour’ magazine was the object of some jealousy and disdain by the newspaper, edited by Harry Evans. The view was that as the advertising financier of the newspaper it should stick to consumer features. Wyndham, the generator of much of its content, had helped make it the leading publication for photojournalism. He commissioned Don McCullin – published his multi-page spreads from war zones – Duffy, Donovan, Eve Arnold; he commissioned Gore Vidal and VS Naipaul. The magazine had become political, a rival at times to the paper in its coverage of Vietnam or Biafra. When Chatwin wrote his early profile of Mrs Gandhi in a personal, anecdotal style, it hit opposition, and was published heavily cut with much feather ruffling.

When the budgets for our travel extravaganzas ended, and we abandoned ship, the new editor, Hunter Davies, reverting to the no-nonsense school of journalism, revealed his brief: ‘To cut back on the big poncy foreign spreads by people like B. Chatwin.’

Bruce was a natural journalist, and a brilliant one: curious, with an osmotic ability to immerse in a subject. In What Am I Doing Here (no query) – his collection of journalism and travel pieces – he shows a deep grasp of the complex, brutal history of colonial Algeria and the appalling pressures on France’s migrant Algerian workers in The Very Sad Story of Salah Bougrine. He sought out contradiction: ‘George Coustakis is the leading private art collector in the Soviet Union’ he began his profile on the Costakis collection of constructivist art – which was a scoop, though more paradoxical then than now. He had a fascinating long interview with a spiky, demoting André Malraux. As ever, Chatwin had read everything; he was highly prepared. He honed his writing carefully, early on, through his journalism, the sensational and exotic always tethered to a sparse prose style which, he admitted, owed something to Hemingway. He began his story Heavenly Horses: ‘The Emperor Wu-ti (145-87BC) was the most spectacular horse rustler in history. He craved the possession of a few mares and stallions which belonged to an obscure ruler at the end of the known world, and in getting them he nearly engineered the collapse of China.’

Bruce often had cause to think “What am I doing here?” He was caught in a staged coup in Benin, formerly Dahomey, in 1984, arrested as a mercenary by the ‘Benin Proletarian Army’, stripped, made to stand in the heat, faced with maddened crowds shouting “Death to the mercenaries”. In those situations fear and desperation for release heightens the imagination; Chatwin skilfully uses that moment of hell to define his paradise outside this terror compound, where a Belgian ornithologist had just been felled in front of him with a blow to the head. ‘No, this was not my Africa. Not this rainy, rotten-fruit Africa. Not this Africa of blood and slaughter. The Africa I loved was the long undulating savannah country to the north, the ‘leopard-spotted land’ where flat-topped acacias stretched as far as the eye could see, and there were black-and-white hornbills and tall red termitaries. For whenever I went back to that Africa, and saw a camel caravan, a view of white tents or a single blue turban far off in the heat haze I knew that, no matter what the Persians said, Paradise was never a garden but a waste of white thorns.’

Bruce was a great talker, nicknamed ‘Chatterbox’ by some of his friends. He would tell his stories to us as a form of rehearsal for his writing; to hear them echoing back. We heard them in different versions more than once. But they were always spellbinding and full of extraordinary information, rendered in a clipped voice. ‘Ludlow’ was his pronunciation of the Shropshire town. His friends existed in different compartments – you never heard much about the other ones, but they cropped up, and sometimes collided. Bruce was – though it is seldom said – full of kindnesses. He lent me, to work in, his austere garçonnière in Albany, the highly restricted barrack-like apartments and walkways opposite Fortnum & Mason. He didn’t warn me that a beautiful Oxford undergraduate, who became a well-known New York novelist, had been promised the space. She appeared in the doorway, beside her lover, holding an open bottle of champagne filling the air with sweat and adrenaline, moving past me towards the narrow iron bed, intent on carrying on instantly where they had left off. I gathered my papers in a fluster of apologies. I had no idea Bruce kept a compartment of the Oxford undergraduate jeunesse dorée.