Pain, pleasure, parties and protests: photographer Vincent Cianni’s images capture 1980s LGBTQ life with intimacy, understanding, and empathy

- TextMiss Rosen

In the early 1980s, a mysterious disease began to infiltrate the LGBTQ community, leaving a trail of death and destruction in its wake. As it sped from one person to the next, a horde of horrific illnesses began to manifest as compromised immune systems made once-healthy bodies the site for devastating, often fatal conditions.

The government and the media turned a blind eye, ignoring the plight of HIV/Aids until it reached endemic levels. The speed at which the disease ravaged its victims and spread from one to the next was exacerbated by systemic, malevolent negligence. People were dying at an exponential rate because there was little to no information on the cause, treatment, and prevention of the disease.

It wasn’t until 1983 (after 1,450 cases, 558 of which ended in death) that The New York Times finally put Aids on the front page when the US government’s top health official declared an investigation of the disease was now “the number 1 priority” of the Public Health Service. Suddenly centered, it seemed Aids was everywhere – and the stigma, brought about by misinformation and malevolence, became something fierce.

“Early on it was a state of confusion, fear, and uncertainty,” remembers Italian-American photographer Vincent Cianni, whose photographs from the era are currently on view at Vincent Cianni: A Survey until April 6.

“These photographs are an outgrowth of my life,” he says of the works, which offer an intimate look at gay culture at the dawn of Aids. Cianni shares private moments from his personal relationships, along with scenes from public life in New York between 1983 and 1992 – though there are some made in the 1970s when Cianni was living in Baltimore of a friend who later died penniless in London from Aids-related illness.

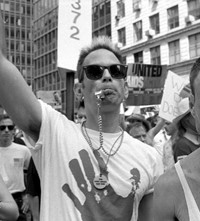

“I have always carried a 35mm Leica around my shoulder, no matter whether I was hanging out with friends, cruising, going to parties or bars, working as a bartender at PrimeTime, a gay bar in Highland, New York, or attending demonstrations, actions, and meetings organised by groups like ACT UP,” Cianni says.

“Looking back, I was young and passionate about living and developing my career, as well as developing friendships and building an extended family – that all of a sudden became subject to this horrible disease. Like any family you begin to realise that your purpose or your role is to care for, support, to help and to fight for these people affected by it.”

Tapping into his practice of community service and organising, Cianni began to contribute to the cause the best way he knew how. “For me, making the photographs was to embrace and embody it, and for it to be a part of who I am. It was going towards intimacy, understanding, and empathy to celebrate and be honest about the gay culture of the 1980s – and give respect to it,” Cianni says.

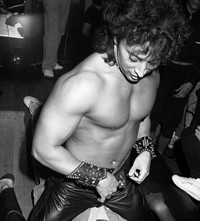

“Coming out of the 70s, and the ‘Me Generation’, you get this era fueled by Reaganomics. The economy was booming. There was a lot of drugs and partying that brought it to a height never seen before. People were able to be out and to flaunt it. You could do whatever you wanted. There was a sense of freedom. It was party ‘til you drop. People would do these extravagant parties until this bomb set off.”

In his photographs, Cianni bears witness to the impact of HIV/Aids as it simultaneously transformed personal, cultural, and political landscapes. “People were shocked when Aids became apparent and the pandemic started to affect a large part of the community. Activists like Gran Fury were organising and forging new ground, using photography and visual history as a way to get messages out and change the way the gay community sees and uses photography for self-representation,” he says.

“I put myself out there in many different ways in terms of photographing. A lot of the pictures include drugs, sex, and sex parties, as well as the activism to stand up and fight for basic human rights – and not being turned into a pariah and the object of hatred. It’s one of my more personal projects, one that touched me very closely. This is a community I existed in very deeply.”

That depth is reflected in the scope of all that has been lost – not just the untimely death of legends like Robert Mapplethorpe, Halston, Keith Haring, Freddie Mercury, Antonio Lopez, David Wojnarowicz, Rudolf Nureyev, and Herb Ritts, but also the people Cianni knew best. “I had an ex-lover die in 1990, then another die in 1993, so it impacted me very intimately,” he reveals.

“Looking back 25-30 years ago, I see a sense of loneliness, sadness, and loss in the photographs. They hold a memory of what our life was and can remind us how powerful that experience was.”

Vincent Cianni: A Survey is on view at Lycoming College University in Williamsport, PA, until April 6, 2019