Cover Story: The Young Activists Calling for Change, Justice and Acceptance

- PhotographyCasper Sejersen

- StylingEllie Grace Cumming

- TextJack Mills

In Another Man’s first digital cover story, we present a portfolio of young activists from New York and London. Each an inspiring voice. Each a tireless force, galvanising communities, transforming lives and reshaping worlds

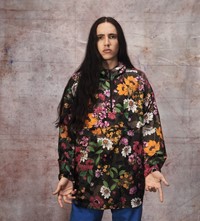

XIUHTEZCATL MARTINEZ (ABOVE)

18-year-old rapper and climate change pioneer XIUHTEZCATL grew up within eyeshot of the devastating fracking wells of Boulder, Colorado. Between TED Talks and his efforts to sue the US Government for gross inaction, he represents Earth Guardians, a youth-powered organisation paving the way for global carbon reduction.

“My upbringing had a huge influence on who I am and what I do. I placed a significant emphasis on my cultural heritage, on my indigenous roots. My father’s an indigenous Mexican. Growing up, I remember travelling across Mexico and North America, to different lands, learning from the different indigenous people, participating in ceremonies, learning my own language, heritage and culture – and the meaning behind my name, my language, my long hair. It gave me a sense of understanding that everything I do is in honour of my ancestors, in the ways that they fought, struggled, sacrificed so that we could be here today. We are at an interesting mid-point between the future and the past, in honour of our ancestors and the next generation. Deeper than activism, deeper than political action, my life has been a journey towards recognising the humanity in me. I fell in love with the Earth, with the ocean, with the force of Colorado. And that showed me what I needed to protect.

When I was nine years old, I organised my first action by putting a call out to young people in the community to fight against the spraying of chemical pesticides in our parks – applying our voices, going to city council meetings and organising press conferences. Not waiting for anybody to assign us leadership, but taking it on ourselves. We won our case. Both as a local organiser and by travelling to different parts of the world and visiting the United Nations, I now spend my time representing my generation and my culture.

Environmental degradation and climate change wasn’t just a far-off concept when I was a kid. Anytime I would go anywhere in the mountains, I would see swathes of forest destroyed by pine beetles due to warming, more sporadic heat-waves during shorter winters. My forest, the one I was in love with, was dying year on year. Wildfires were clearing massive portions of land, and I’ve been evacuated multiple times because of them. The floods that came through were absolutely unprecedented. Natural gas extraction is an industry that is leading to the collapse of our planet, and I can see it in my backyard. It’s destroying the air quality, the water quality and is making my community, my family, my people, sick.

The anger and the strength it feeds you with, makes it impossible not to turn it into action. What’s powerful about that issue of fracking, too, is that everyone is angry as one – from conservative communities in the suburbs to progressive, Democratic communities in the mountains. So it’s not just a partisan issue.

I wanted to be heard. When I was six, I felt as though my voice could help people understand the way I saw the world. I wanted to share that with people and I wanted people to take action. I wanted people to be angry and to be inspired and excited. From the beginning, there’s been an underlying understanding that my voice has power. If I share it in the right way, I can help share that power with other people.

“Deeper than activism, deeper than political action, my life has been a journey towards recognising the humanity in me”

Since its conception in The Bronx in New York in the late 70s, hip hop has always been about speaking the truth. Because rappers often come from difficult situations, hip hop is the voice for oppressed minority communities. You have a responsibility as an artist to reflect the times. In my art, in my music, I am inspired by the greats: Afrika Bambaataa, Yasiin Bey and Talib Kweli and, as time proceeded, Joey Badass and Kendrick Lamar.

In 2015, I filed a new lawsuit called Juliana v United States of America and that is going down in history. It’s pretty remarkable, the distance it’s come, especially with Trump in office. I think movements throughout history have shown examples of youth utilising our justice system to bring about change. But the way the existing environmental movement has been working for the last several years is not successful. It’s not enough. The case is saying a lot more than simply, ‘You’re not doing enough.’ It’s saying that over the last 50 years, there is recorded evidence of the US government keeping information from the world and of supporting the fossil fuel industry with the knowledge that it is leading to the detriment of the climate. It’s not just that they’re not doing enough about it, they’re actively propping up the very industry they know is creating massive disturbances.

This year, we’re launching an app that’s going to become the simplest way for people to understand their impact on the world and how to make tangible changes every single day, from lowering your carbon footprint and the amount of water you waste, to lowering the amount of plastic you use. It’s gamified too – there are leaderboards, you can challenge your friends. We’re going to be distributing it to 20,000 classrooms.

Another project we’re working on is sending a crew of young people out to share the truth and the message. It’s a project called Voice Runners that’s paired with an album. How do we bring these young people’s messages to the majority of the population, to show the world that the people getting all the media coverage – people like Trump, for example – are not the ones who are truly making noise or truly creating change? In the coming years, young people are going to be taking that power back.

It’s not going to be changing our light bulbs or our methods of transportation that changes the world. It’s a step in the right direction, and it’s critical, but there are systems in place that have created a world that depends on the depletion and exploitation of resources and communities of people to create wealth for a very small percentage of the population. The first step is to understand your impact. From there, go to your school, to your family, to your community. The way we consume every single day is an opportunity to challenge these systems of capitalism and greed. Work up to a massive piece of action, work up to federal lawsuits. Partner, connect, collaborate.”

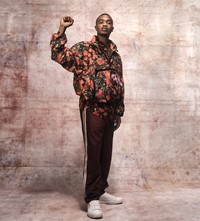

CLIFTON KINNIE

The murder of Michael Brown by a police officer on 9th August 2014 sparked one of the biggest race riots in recent American history. At the centre of the Ferguson uprising was 12th-grader CLIFTON, who organised mass walkouts, protests and voter registration drives across 30 schools in the surrounding St Louis area. Today, on stages across the world, he brings a message of oneness.

“I’m one of so many young leaders that are on the ground working right now, for what I regard as our reiteration of the civil rights movement. A month before Michael Brown had been killed, my father was living in a nursing home due to a stroke. I had just lost my mother to stage four breast cancer. Yesterday was my father’s birthday – he passed away in September 2018. During that time, the summer of 2014, I was depressed. I shut down. Prior to that, I was always involved in my community: team leadership programmes, that sort of thing. It wasn’t until Ferguson that I used my skill sets to make change.

I saw Michael Brown’s body on Instagram on 9th August. I thought it was fake until I realised it was right around the corner from my school and my grandmother’s home. That urged me to get out there. I always tell people, if you had taken what you could see that day and put it in black and white, you would’ve thought it was 1955 in Montgomery or 1963 in Birmingham.

That young black boy was left dead in the streets for over four hours. We saw that, and the police responded to us with tear gas and rubber bullets and mace and dogs and tanks. I went to school and my teacher was talking about how everyone was wrong to protest, that they were ‘thugs’ and ‘looters’. She couldn’t understand the cause, she couldn’t understand the pain and frustration that many of the people in Ferguson had. And that really angered me.

I got up and I left the classroom, went home and texted a bunch of my friends. Twenty of them came over. Then 30 more people showed up, then 50. Then 100 students were in my backyard. That’s when I realised what we did was build youth power, collective power. That was our first introduction to organising.

“I’m not a gun violence activist or gun control activist or a police control activist. I am here to bring about a more just society, a transformed society”

We didn’t get too much credit at the time, because we were young, black and intelligent. We had a vision, and that’s dangerous in America. After the initial protests, I met with President Obama. I just kept thinking, ‘How could a black president keep us safe in America, at a time when young black boys and young black girls were being gunned down in the streets?’ I knew that six million young people would be watching this interaction. I asked him, ‘What does safety look like, outside of police and prisons?’

We agreed that safety was access to housing and healthcare and jobs and education. I think at this point in the movement folks are trying to figure out whether communities need policing at all. What does policing actually look like in today’s age? Can we reform the police? Are the police even willing to be reformed? A lot of institutional work has to be done, but the groundwork was laid. Back in Ferguson, we didn’t know we were doing that.

Ultimately, my goal is not just to police. I’m not a gun violence activist or gun control activist or a police control activist. I am here to bring about a more just society, a transformed society. My ultimate aim is to build a mass mobilised international movement that will ensure that people have access to their basic needs. We need to shift our values. Part of that is going to require the work of our lawmakers, our community organisers, our professionals, our artists. I like to call our artists, our ‘artivists’. Internally, we have to figure out who we want to be as individuals. Externally, we need to figure out the kind of world we want to live in as a collective.

I travel a lot. I speak to so many young people across the country. I’m supposed to be going to the UK to speak at Oxford University. What we’ve seen throughout history, is the power of the people push. I always say, teachers are our modern day abolitionists. Education is so pivotal because it provides you with a river of knowledge. I didn’t receive my river of knowledge until I met Mr Vargas. He was my Pre-AP US History teacher at Hazelwood East High School. He taught me not just about Dr King, but about all the black youth that were on the frontlines during the civil rights union. All the black women... He showed me that you can become the people that you read about, you know? You all are the leaders of today. It wasn’t just the history, it was that you can transcend your society.”

ELIEL CRUZ

ELIEL is a public speaker, writer and community organiser focused on faith and sexuality, bi-visibility and ending violence against the LGBTQ+ community as a whole. He founded a social media series called #FaithfullyLGBT encouraging the LGBTQ+ faith community to share their stories, and is presently director of communications for the New York City Anti-Violence Project.

“My advocacy came out of necessity. Growing up in a conservative, Christian, pretty much fundamentalist denomination. I went to church every week and only ever went to conservative christian schools – I was in this bubble of anti-LGBTQ+ theology and impurity culture. When I came to realise my sexuality, there was no shame around my sexuality until there was shame placed on me by my community. Essentially all the violence I faced growing up came from a religious community which impacted how I viewed my own theology, and my own relationship with god. Even as I evolved and came to a better theological understanding of my sexuality and my relationship with God, I still had this friction and trauma with religious communities.

#FaithfullyLGBT, as with a lot of my activism, was an evolution. I had a column at Religion News Service – which is, I think, the largest religion wire service in the world – writing about sexuality and faith two or three times a week. I was still an undergraduate at a Christian school, organising on campus to make spaces safer for LGBTQ+ people. I say ‘safer’, because those spaces will never be safe completely. The name of my column was called Faithfully LGBT. I was, and am, so involved with the LGBTQ faith community and as I was writing and speaking, I was coming into contact with a lot more. In my organisation work, there was a large dichotomy in the media between religion and LGBTQ+ – that the two were completely separate. It was accurate of my own experience, but it wasn’t the experience of thousands of people that I was coming into contact with in these communities. I started a hashtag to keep track of all my writings and was also involved in a community that were sharing their own articles about LGBTQ+ faith experiences.

I was going to conferences that were LGBTQ+ faith-specific and noticed there was a rich amount of stories and experiences that deserve to be told and to be heard. But for me and my work, Faithfully LGBT aimed to disrupt that dichotomy that’s so pervasive, because if we uplift these stories and show that LGBTQ+ faith exists, it inherently disrupts it. I started to collect those stories because no one else was.

My organising comes from the way I was raised. My mom was a social worker and went above and beyond to help underprivileged communities. I grew up in such a religious bubble that everything bad I experienced came from the hands of religious people. Turning that into working so that no one experiences even a little bit of the violence that I went through made sense for me.

“I find it increasingly important to share LGBTQ+ faith stories, especially in the United States where evangelicals have unprecedented political capital compared to any other religious group”

My work on bi-sexuality came out of seeing that there was a lack of understanding, a lack of fluency around it in popular media and popular culture. So much has changed in the past six or seven years since I started writing. The amount of bi-sexual celebs that have come out has multiplied.

My work is on the ground, organising in those various communities: faith, bi and, broadly, the anti-violence movement. Using the media to shine light on these experiences and creating spaces for people to be able to share their own stories. My writing doesn’t come from theoretical understanding, it comes from my work experience. For me, that’s really important. To write from a place that’s not just my own personal experience but my own work experience versus offering broad advice that doesn’t have any tangible impact...

My activism is essentially a type of storytelling rooted in organising work and being part of a community. For me, storytelling and all the work that I’ve done has created the lens for us to have these pivotal conversations. When we talk about marginalised communities, typically we’re spoken about in a theoretical fashion that doesn’t have a humanised dimension. For me to create campaigns and spaces for people to share their own stories, it begins to level the ground for us to be able to even have a conversation around policies that impact people – how various theologies are having harmful and often fatal impact on LGBTQ+ people.

This year, I’m going to be working on expanding my faith and LGBTQ+ campaign – I find it increasingly important to share LGBTQ+ faith stories, especially in the United States where evangelicals have unprecedented political capital compared to any other religious group.”

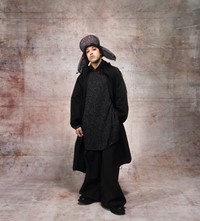

JANUARY HUNT

JANUARY is a noise musician based in New York. Like the city’s alumni of No Wave pioneers and Beats performers, her visceral and boundary-breaking sounds point at society and state, and the wider power structures that regiment us. A trans artist who legally changed her identity eight years ago, she currently performs under the stage-name New Castrati.

“I came up with the New York punk scene as a teenager and it shaped my world-view. When I started transitioning, punk started to alienate me, so I got into more extreme kinds of music that felt as dissonant as I felt at the time. It led me towards freakier electronic music and scenes that embraced different kinds of bodies and identities.

I think I’m very privileged in that my mom was always pro me making art, seeing the way that it offered an escape from the dominant culture for her, and how creating art kept her alive in a lot of ways. She went to Woodstock, she was part of the anti-war movement of the 60s. She became an emancipated minor from her mom 50 years ago. That stuff influenced my world-view – politically, especially. It would be hard for it not to.

For a short while I worked in the makeup industry as a means to come out as trans and deal with that. I figured it was a world that would be inclusive, but I got wrapped up in it and worked for a company that went on to be successful. I lost myself in that process.

“The theme for me, over time, has been autonomy; creating an autonomous atmosphere for people who feel alienated by the dominant culture to go and spend time in”

A lot of trans women that make electronic music have had that experience. There’s this idea of shaping technology – shaping electricity that comes from a power grid which is in itself a structural, oppressive thing. I think of this overlord of technology and capitalism as intertwined. To me, music has largely been about taking electricity from that and reshaping it through the filter of my body and my world-view.

A lot of my inspiration comes from old New York queer people, pre- and post-Aids, as someone who is from New York who is kinky and freaky and gay and trans. Changing my name was something that felt necessary as a trans person. On 1st January 2011 it changed forever, legally. I had gone through all the loopholes to change it on every single document, just to see how far I could go to pursue this piece of bureaucracy.

It felt like a political gesture, because I wanted to be more coherent with my trans identity. I started taking hormones in January, my mom was born in January, I came out on 1st January – all these things made sense. It just fitted into this place that felt impossible to fill. I’ve been chasing that feeling again with my music projects.

The theme for me, over time, has been autonomy; creating an autonomous atmosphere for people who feel alienated by the dominant culture to go and spend time in. New York’s noise and experimental scene is super-intersectional, more than any other scene I’ve been a part of and I have been a part of many. I feel like I see all sorts of bodies and identity groups and different sexualities, all intersecting in a desire to escape through a community; through autonomy, or through music.”

ENID ELLEN

Together with Greg Potter, drag artist, poet and polemicist DAVID MRAMOR makes music as ENID ELLEN. ENID’s Rust Belt beginnings and Christian Science classes drove them to New York to explore painting and performance art. Songs like Orlando and Protest Song tread a line between fantasy and escapism, and the dangers of complacency in tense times.

“Enid is the name of a character from a board game called Sweet Valley High, which was also a TV show. She was the one who had red hair and freckles, and if I was going to play the game, I would have to be her. Nobody else really wanted to be her.

I grew up in a very conservative Republican area outside Cleveland. I attended a Christian Science church, where they didn’t believe in taking medicine, it’s all healing through prayer. Maybe it introduced me to alternative thinking. Mary Baker Eddy was the hero there. She fell on ice and was bedridden and she wrote down all the teachings from there. I thought she was really amazing, she was my first real connection to feminism.

At this time, my access to other queer people was very limited. But, as soon as things started to change in the 90s, Ellen DeGeneres came along. Her coming out of the closet was really amazing. There was always this feeling that I had a connection to her, but I didn’t know how to put it together. Then I moved to New York to attend grad school.

“It’s about creating a space in which people can feel free to express themselves, and make mistakes. I’m pretty sloppy at times. I’m not a polished, pageant-y kind of drag queen”

I started making art that involved lots of dresses and wigs and more feminine-binary fashion. I started painting in my studio when I was dressing up, especially when wearing heeled shoes for some reason. It put me in a different state of mind, an altered state. When I first moved to Brooklyn, it was pre RuPaul’s Drag Race. There wasn’t a lot of drag going on at the time, so I was kind of figuring out how to navigate that. Now there’s more and more, I can’t help but think it’s because of the political power and activism that has emerged right now. I put it all into the music and allow the anger and emotion to come out that way.

It’s about creating a space in which people can feel free to express themselves, and make mistakes. I’m pretty sloppy at times. I’m not a polished, pageant-y kind of drag queen or anything like that. A lot of times the clothes that I wear are borrowed or they’re from my mom after she passed away. I connect to her in that way. There was a drag-convention here right around the time of the Kavanaugh hearings. I had so much rage about it, but I thought, what better way to express that feeling than go to the convention with my message? How can I use this art form to allow people to express themselves and express my own anger, too?

I also teach Kundalini yoga, which is all about building your nervous system so you can be a strong human being. So many of the exercises involve shaking and screaming and punching. You do it with your eyes closed, and in your own space. You’re not invading anyone else’s. It makes me think about all the times I marched up Fifth Avenue to protest and scream after Trump’s election. The energy and connection we created together was so big and amazing.

Our next single Protest Song is about not being complacent as we continue to move forward. I think especially nowadays, social media can make us hide away. It’s so important to show up at a protest, even just to be another body that’s present at it. The numbers actually do count, connecting to people does count. My old Christian Science Sunday school teacher would call it a ‘ripple effect’, that you can’t make huge changes walking out there by yourself. You throw a rock into the water and all the ripples, together, create waves.”

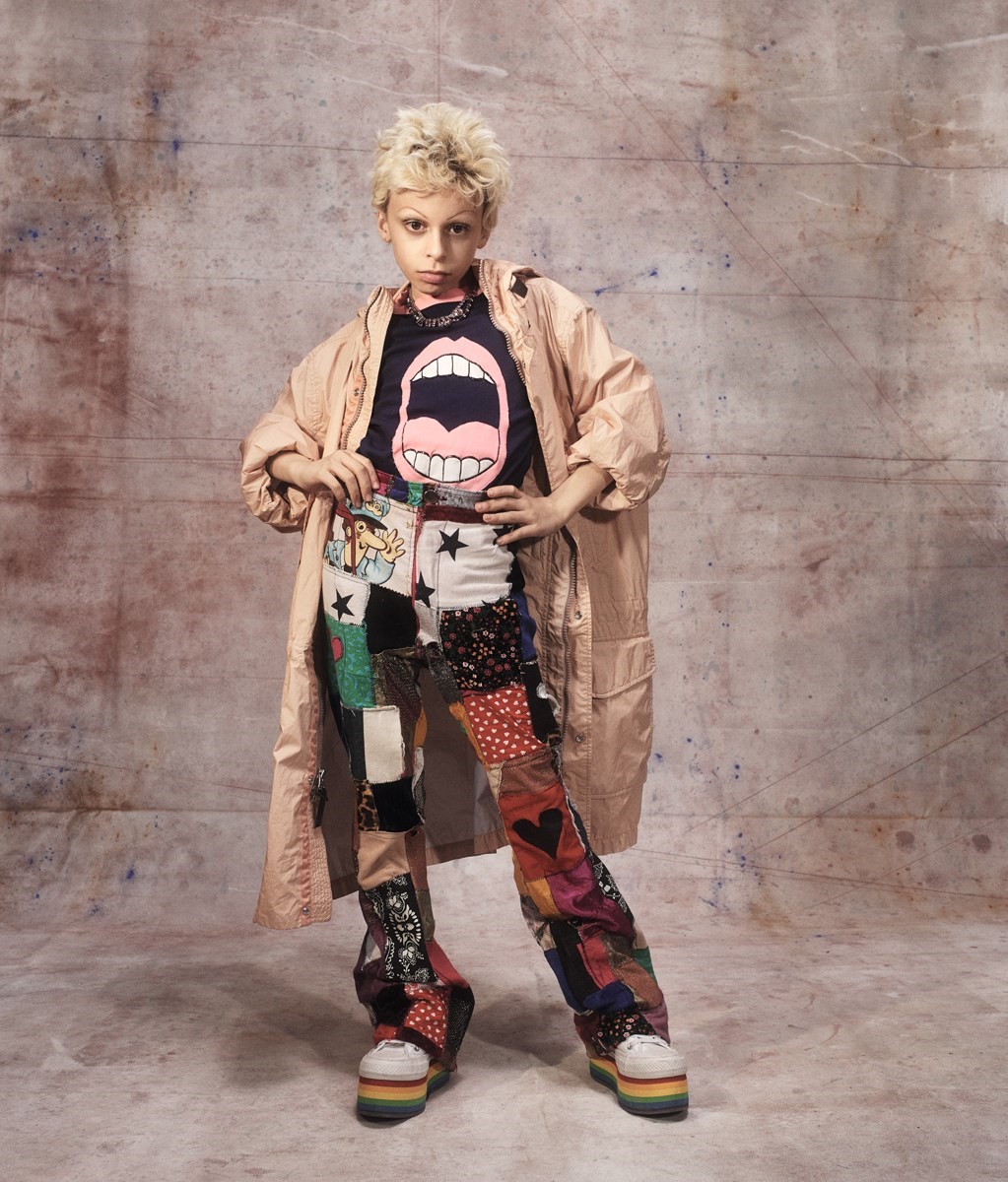

DESMOND IS AMAZING

11-year-old drag artist DESMOND was born on the same week as New York’s 2007 LGBTQ+ Pride festival, an annual event to commemorate the Stonewall riot and the enduring sense of solidarity it instilled. A Manhattan-based campaigner for equality and freedom of expression, DESMOND and his mother founded Haus of Amazing, an international networking platform for drag kids.

“I first wanted to be a drag kid when I watched episode one of series one of RuPaul’s Drag Race. I was two and playing with my toys, and stopped to watch it with my mom. I thought the drag queens were so beautiful, like princesses or something. RuPaul inspires me because he went from being a club kid living on the Lower East Side in New York City, to the super-successful person he is today. Anyone can live their dream.

In 2015, one of my mom’s friends created a page called ‘Desmond is Amazing’ after I walked in the New York City Pride parade. I loved the name so much I decided to adopt it as a stage name and it just stuck, it wouldn’t come undone. I started Haus of Amazing because I felt like there should be a platform for drag kids. We were going to start it on Facebook, but we got a mass hate attack, so we decided to do it on a private network. It’s still a work in progress, but me and my mom are hoping it will be done by summer. I’m just going to keep going, no matter what I have to push through. If I have to push through a whole wall of haters I will, and become a bulldozer. It will be on a private network where drag kids can socialise, and adults won’t be allowed on there – except in a hidden part where parents can connect. I think it’s showing that kids can do drag, regardless of what people think. I want drag kids and kids who are interested in drag to be able to come together in a safe place online. Eventually, I want to build it to include meet-ups and events.

I’m an LGBTQ+ activist and advocate. I go to the Aids Walk and the Aids Memorial. I think more people should be LGBTQ+ advocates because the more people, the more power. People should be able to express themselves and not be afraid to be who they are in life. My motto is, ‘Be yourself, always no matter what anyone says and pay the haters no mind because they will never be as fierce as you and I.’ I think I’m gonna be the same for the rest of my life – except I won’t be a drag kid anymore, when I turn 18.”

JANAYA ‘FUTURE’ KAHN

Public speaker, teacher, Afrofuturist and gender non-conforming JANAYA is the co-founder of Black Lives Matter Toronto and the programme director of Color of Change, a racial justice organisation. In their nascency as a professional boxer, they learnt of the transformative potential of group action.

“Growing up I lived in public housing among a community of disenfranchised people, but that’s not what it felt like. It felt like home. Everybody sort of looked like me. I think that when you are somebody who is non-normative, meaning you don’t fit into this mythical norm of what everyone else is positioned against, you’re a political being – but you might not know that you are. What exactly politicised me, though, was actually boxing.

I walked into a women’s boxing club by happenstance and it just so happened to be the first women’s boxing club in Canada. And it was full of weirdos and queers and dykes and trans folks and survivors. Being in that space with them, having a sparring partner who was a trans man – I’d never really had an opportunity to connect with somebody on those terms. I’m sure we’ve all met trans people whether we knew it or not, but it was the first time someone was saying to me, ‘This is who I am and this is what I am.’ I thought, ‘How audacious and how amazing.’

The gift that boxing gave to me – the community and the skills – I knew that I wanted to bring that into other places. At that young age, I wasn’t adept at talking about racism or sexism or classism. But I knew boxing. I would take gloves to any conference or convention that I went to and teach people how to box. It gave them, I hope, some of the same feelings that I got from it. As they learnt, I began to learn too. Here I am, over a decade later, and I still box, still competitively. It created the foundation for me to become an organiser, an activist and a storyteller.

“Activism is just being the person that you needed in your most vulnerable moments. It’s not always the protest and the rallies, it’s coming out of your fear and into your power”

The nickname ‘Future’ came to me in 2015 at the first ever Black Lives Matter convention in Detroit. It was the first time that we had all gotten together and it was brilliant. There was just so much energy and so much joy. I know that seems so contrary to black militancy, but joy has always been a part of resistance work. Because of the way that I dressed – but really because of my ideas – people started calling me Future and it just stuck. It’s become so pervasive that I had to put it on my immigration documents.

We’re just in such a difficult time, and my job now is to remind people to move past political nihilism. It’s to remind people that it’s not too late to become the person you always thought that you could be. That activism is just being the person that you needed in your most vulnerable moments. It’s not always the protest and the rallies, it’s coming out of your fear and into your power. Anger comes from an honest place, it means that you know something is wrong inside of you and you’re not quite sure how to fix it yet.

I’m the programme director at Color of Change. Part of my work is looking at what stories need to be told and what stories need to be reframed in a more balanced way. People often think that protest is the first thing that we do as organisers. More often than not, it’s one of the last resources that we are forced to take when other forms of intervention haven’t happened yet. I’m a huge proponent of using fashion as a means of intervention. I think part of my experience as a gender non-binary person is being who I most authentically am and part of that is looking at how I dress and how I present – which gives people permission to do the same. I think culture – whether it’s TV or op-eds or radio or clothing – is so deeply connected to protest. When I say protest, I don’t mean just being on the street. I mean GIFs, I mean memes, I mean hashtags. We are cultural producers, and our movement could not have been effective without it. Each of these things are a protest but not seen as a protest. I look at painting as protest. I look at movies that tell a different story of queer people as a form of protest.”

LUKE HUMPHREYS

As a teenager, model and LGBTQ+ campaigner LUKE energised conversations around identity in his conservative rural hometown. Now, he is using a flair for fashion design to deliver a message of acceptance.

“I grew up in Darwen, a really small town in northwest England. I was a really angry, reckless teenager. I started feeling political at 19, 20, when the conversation was leading into a less binary way of thinking in terms of how we view sexuality and gender. My hometown is quite small and closed-minded, people felt they couldn’t talk about the things they were facing, and I felt responsible for encouraging that conversation. I worked with the council to get LGBTQ+ youth groups opened, and the neighbouring towns were so impressed with what we were doing I was invited to meetings to talk about it. Soon, more groups were opened in neighbouring towns.

Aside from this kind of work, I collaborated with another local organisation called Reach Out. We held a big fundraiser in town for drug addiction, alcohol addiction and raised money for the local rehabilitation centre. I very much like to be one-on-one with people and communicate with them directly, and know exactly where my work is going and who exactly it is helping. There’s an organisation called Albert Kennedy Trust which specialises in housing for LGBTQ+ homeless youth. When I was younger, there was a period when I wasn’t allowed to live with my family and I was relying on the kindness of friends and organisations that housed people. I think there’s a statistic that says that 80 per cent of homeless youth feel there is a direct correlation between their homelessness and their sexuality.

“I was a really angry, reckless teenager. I started feeling political at 19, 20, when the conversation was leading into a less binary way of thinking in terms of how we view sexuality and gender”

At that age, I didn’t really have anyone to look up to or relate to. Obviously we had more progressive celebrities like Freddie Mercury and Bowie, but when you look at someone through that celebrity lens, you don’t acknowledge them as a real person. I try to engage as much as possible with young people to offer advice, and to be seen as a regular person going through what they’re going through. I wouldn’t be sat here today had it not been for the friends and supporters who reached out to me outside of the heteronormative environment.

By the end of the year, I plan to release a collection of bags and accessories and collaborate on it solely with LGBTQ+ people, coming together to create something that is really poignant in its message. Its essence, and where the concepts and the colour palette and the shapes come from, are inspired by our history and the fight for people’s rights. Rather than it offering a flat-out pride vibe on the runway, it’s subtle in that even if you don’t know about these things and you might not necessarily relate to it, I want you to be inspired to find out.

The fashion industry has acknowledged its responsibilities somewhat, but this is more evident in independent designers like Chema Diaz, who I’ve modelled for. Some of the high-profile luxury brands still have so much more to do. I think they’re following the lead of these smaller designers, but sometimes I feel it lacks sincerity.”

DECLAN WELSH

In 2016, the lead singer of Glasgow band Declan Welsh and the Decadent West went to Palestine to perform and ended up being tear-gassed on the frontlines of a protest. He believes in the radical power of compassionate music.

“My parents weren’t particularly political. East Kilbride, where I’m from, is the Milton Keynes of Scotland. It’s just roundabouts, a shopping centre and some houses. Boredom, more than anything, is the biggest thing it gives you. The Scottish Independence referendum, at the time, seemed like it could be a really good means to an end – not to say that I’m harbouring any nationalist sympathies whatsoever. At school I was a big fan of the Scottish National Party, but I wouldn’t say that I am any more. That is probably when I started combining music and art, and started writing political songs. Under Corbyn, this is the first Labour party that has even been approaching left in my lifetime.

It was interesting to see how many young people were engaged with the referendum. If you’re in Glasgow, which is a city that is probably more left-inclined than others in Scotland, you’re basically surrounded by communists and artists. One of my uni pals told me about Billy Bragg, whose words I got tattooed on my arm.

The best kind of political art is something that shows you how different the world can be, as opposed to a call to arms. All my favourite songs and books and films are generally about love and heartbreak. I like stories, personal stuff – I think all art is political. I don’t think it’s a detriment for things to be about a human experience. It’s a really good place to start from if you want a society that’s a bit fairer. The role of art is to make people feel like they belong in the world.

“The best kind of political art is something that shows you how different the world can be, as opposed to a call to arms”

You can’t retreat into cynicism because that’s a really easy out. I think to create good art, you need to be interested in people. It’s like the Woody Guthrie song, This Machine Kills Fascists. But it’s not the guitar that does it, it’s the people who hear the songs and feel galvanised by them. There’s a place for that. The best way to change people’s opinions is to connect with them and bring about compassion in a society that is completely devoid of it and actively encourages the opposite. Communicating your own feelings and trying to connect with people, fundamentally, is an act of resistance.

When we played in Palestine, I didn’t go there as an artist, I went there to show solidarity. I had a guitar and they had a music festival, so that was the way to get in and we took part in a protest. I wouldn’t compliment myself for doing that: we went there to learn and we learned. That’s why Palestinians want Westerners to come over, so they can show you what it’s like and you can start telling everyone that’ll listen about it. It was a privilege to go and now I have a duty to try and inform as many people as possible. I think more and more people are realising that what’s going on is akin to what happened in South Africa and you can’t really stand by and let that happen.

We got tear-gassed at the protest and it was quite terrifying, but there were kids as young as six saying, ‘Don’t worry, if they tear-gas you, you can come into my house.’ How depressing is it that someone that young is tear-gassed so many times that they’re not even bothered by it anymore?

Going forward, we are doing a gig with an organisation in Clyde called the Rosey Project, who are teaching sexual assault, gender equality and consent classes in high schools. It’s not that there are bad people who do terrible things in terms of sexuality against women, it’s that we’re living in a culture where you’d struggle to find any man who has not hurt someone, being part of a culture that does not train you to be empathetic.

That gives me hope for actual change. Get to everyone when they’re 11 or 12: ‘You have to ask for fucking consent.’ Think about the amount of hurt you could avoid for future generations...”

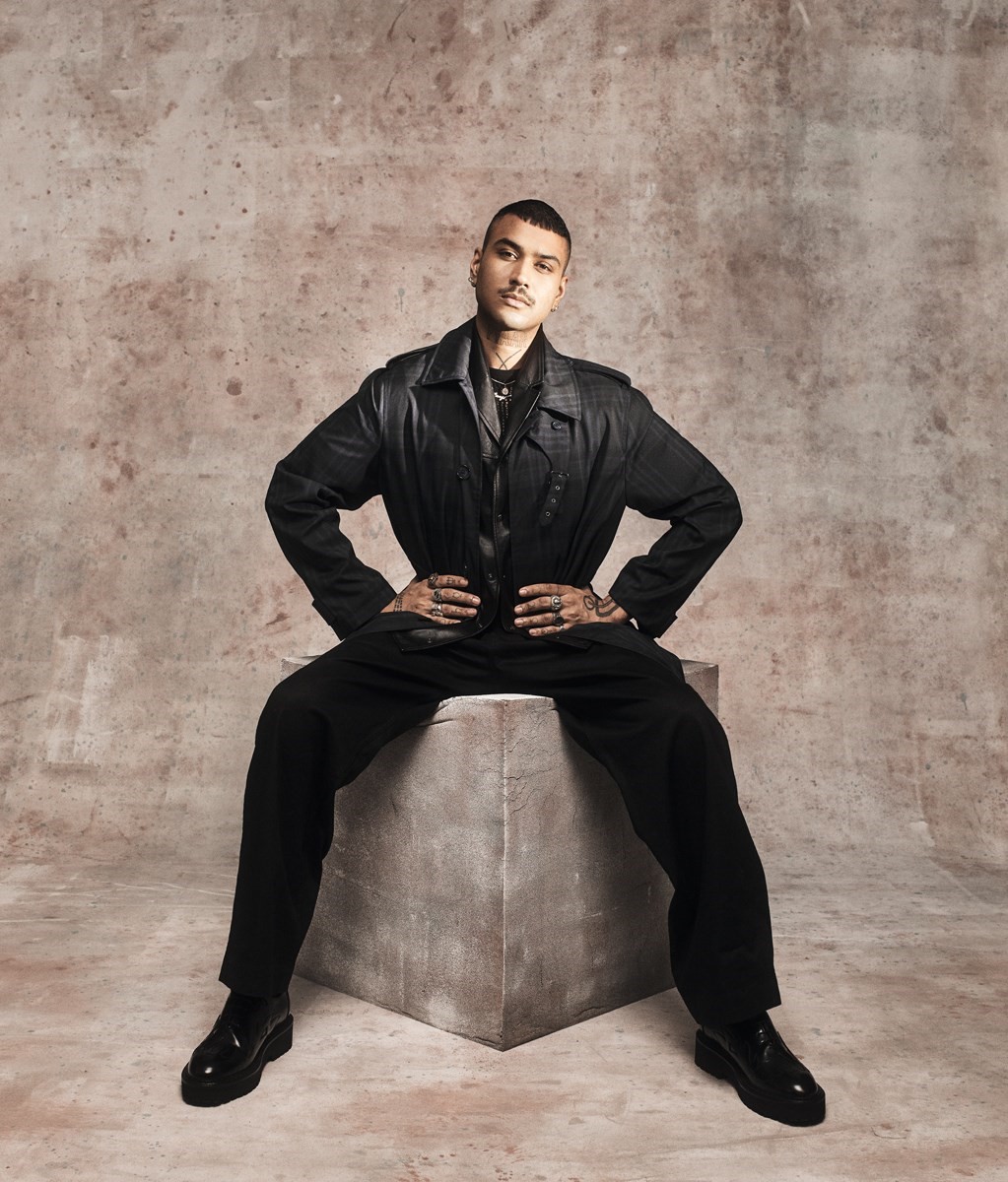

RYAN LANJI

Somewhere between a rave and an act of resistance, Hungama is the UK’s first LGBTQ+ Bollywood club night. Its founder is Canadian-born, London-based curator RYAN LANJI, who is using his spotlight to raise awareness about attitudes to sexuality prevalent in South Asia.

“I was born and raised in Vancouver, Canada. I studied film production before dropping out. At that time, I felt like I wanted to be in one of the epicentres of the world. I found out that I could become British because my dad was born in Birmingham. Without thinking twice, I saved up all my money and I moved to London.

I started working at as many galleries as I could volunteer at. I got a job at a gallery and they asked me to put on a show about nail art. It wasn’t until last year when I went home to visit my family, that I realised by being in London for almost eight years, I had never really connected with my childhood. When you move somewhere and you really start to try to integrate, you don’t question your identity.

I decided to ask the night club The Glory in east London whether I could throw a Bollywood night. I hadn’t thought of it any more than that – I just wanted to play Bollywood music for the queer scene. It effectively became a rekindling of the relationship I lost with my mum. We listened to Bollywood music together in the car, at home. I would DJ as a kid, setting up all the songs on cassette tapes in another room so that my aunties could dance, and I remembered how much fun it was and how much love they had for each other. That was something that I really missed. After I did it I tried to get feedback and people said that they also never thought that they were allowed to be South Asian or to listen to that type of music. Our culture doesn’t really create spaces or places for our people. You’re either gay or you’re Indian. You can’t be Indian and gay.

“I think club culture really underpins the sense of being a rebel or being a freak or being a runaway”

I didn’t realise the political power of it, because I was using it to try to rekindle a sense of belonging. I’m currently working with Naz Project, which is a charity tackling health issues in minority communities. I am working as an ambassador to teach and educate South Asian men who sleep with men to get tested more regularly.

I think club culture really underpins the sense of being a rebel or being a freak or being a runaway. I didn’t feel like I belonged in London, most of the LGBTQ+ scenes are very white-centric. The party has allowed a space for us to come together and create a hub. We’re showing that we are proud of who we are and that we are able to integrate and accentuate the LGBTQ+ scene and inspire others. People have messaged me saying it gives them hope that they can face coming out to their families, or realise who they’re really meant to be, rather than live their life according to other people’s expectations.

The first night we didn’t even have a DJ. I was playing off Spotify and I didn’t know how many Bollywood songs I would be able to access. A lesbian couple told me they got married recently and didn’t realise that the songs that they played at their wedding they’d be able to hear at their favourite gay club. Sometimes we throw the night and it’s hardly attended, but the people who do come tell me they’re so happy that nights like this exist for them, that they feel like they are part of something. I’ve had someone fly over from Germany to come. They had to leave to get their flight back at 3am.

Hungama means chaos and bedlam. It’s the idea of having a night where it’s not really about the type of music, but the feeling of the space. We can move from a Bollywood song to hip hop to an ABBA track; everyone’s having fun to it. It’s showing that Bollywood has a place in the soundscape of culture.”

SHAHMIR SANNI

In March last year, SHAHMIR exposed criminal overspending at the core of Vote Leave’s Brexit campaign. A whistleblower who demanded more from UK democracy, he regularly speaks out on the hypocrisies of the British state and of the lingering trauma that the experience dealt him.

“Since my childhood, I’ve worked to deconstruct my own biases. I was privileged enough to have been educated well in Karachi in Pakistan, where I was taught critical analysis. It was one of the very few schools where you could deconstruct anything, so in your own way you could criticise things like Islam or the Pakistani military or the government. You become more empathetic to social justice, so that systems don’t disadvantage those at the bottom. Even my Euroscepticism stems from that, from my identity as a Pakistani, from my distaste and dislike of white supremacy and anything that propagates these ideologies. For me, the European Union was an emblem of that.

My involvement in British politics comes from this, even though it’s an awful way to go about helping people. I’m not saying that because I’m on my high horse. I genuinely find that the experiences you have as a kid in Pakistan moulds you into caring about right and wrong, because otherwise people get murdered, they get raped. When I realised what went wrong at Vote Leave, my first thought was that the public needed to know.

When the story leaked, there was no one to look at to say to myself, ‘Okay, they did it. I can do it too. I can come forward too.’ In this country specifically, there has never been a whistleblower that has come forward on this scale, especially this deep within Westminster. Edward Snowden and Chelsea Manning in the US are the two I can think of.

“For me, as soon as you get a platform or any clout, use that to push other people like you up. I’ve been alone in this political sphere for too long, but I’ve come to understand the way these power games work”

I’m very grateful for the support I’ve received, but it’s not been worth the risk to my family, the risk of that trauma. I have PTSD now because of establishments like the BBC who were attacking me for no reason just because I was critical of their coverage, as a citizen, as a licensee here. I’ve gone through very traumatic periods of my life. It happens growing up in Pakistan, especially Karachi – once the world’s most dangerous city.

I was having drinks at Downing Street. I was chilling with cabinet ministers. I was as far deep as you can go within the British political establishment. It’s all quite surreal, I never imagined that I would go against this powerful establishment, to reveal the networks of organisations that collude together to bring a specific message to the public, and the scale of corruption and willingness of our leaders to go as far as they need to go.

The first time I met Carole Cadwalladr, the Observer journalist who broke my story, I still hadn’t decided whether I was going to come forward, because I had only just begun to understand that I was going against cabinet ministers. I was putting the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in the hot seat. For me, it was about finding the right journalist. It was about telling the story in a way that resonated with the public. Her work is so grounded in evidence and facts but also in storytelling and engaging the public in a way they can understand.

In other countries, in Canada, or even in the States, if there was confirmation of something like this, they would have re-run the entire election and put people in prison. But in Britain, there’s an abject silence. That silence has caused Brexit. That silence is what has propagated these systems within Britain for decades, for centuries even.

What I’m doing now is focusing on platforming the LGBTQ+ community and queer people of colour, that’s where my heart is. For me, as soon as you get a platform or any clout, use that to push other people like you up. I’ve been alone in this political sphere for too long, but I’ve come to understand the way these power games work. I’ve become a sort of consultant for organisations that are trying to break through, by helping them realise that you must either destroy the game or play the game. You can’t nice your way through it. I’m trying to work on a film project focused on tackling the perversions of democracy, how you give people the tools to protest.”

NEW YORK

HAIR Tina Outen at Streeters using Bumble & Bumble MAKE UP Jen Myles at Streeters using MAC Cosmetics SET DESIGN Jabez Bartlett at Streeters DIGITAL OPERATOR Chris Parente LIGHTING ASSISTANT Tyler Roste STYLING ASSISTANTS Jordan Duddy, Isabella Kavanagh, Alex Assil HAIR ASSISTANTS Bibb Dickey, Rochelle Walker MAKE UP ASSISTANT Aya Kudo SET DESIGN ASSISTANT Raph Fineberg PRODUCTION Artistry London LOCAL PRODUCTION Rhianna Rule POST-PRODUCTION Frederik Heide at Casper Sejersen Studio SPECIAL THANKS Attic Studios New York

LONDON

HAIR Kei Terada at Julian Watson Agency MAKE UP Mathias Van Hoof at M+A MANICURE Saffron Goddard at Saint Luke using CHANEL Le Top Coat & CHANEL La Crème Main Texture Riche SET DESIGN Jabez Bartlett at Streeters DIGITAL OPERATOR Roland Gopal PHOTOGRAPHIC ASSISTANTS Dan Douglass, Barney Curran STYLING ASSISTANTS Jordan Duddy, Isabella Kavanagh HAIR ASSISTANT Natalia Alves MANICURE ASSISTANT Natalie Pencille-Gordon SET DESIGN ASSISTANT Kit Falck PRODUCTION Louise Mérat at Artistry London POST-PRODUCTION Frederik Heide at Casper Sejersen Studio