The Photographer Who Documented His Sex Work and Hookups Through Polaroids

- TextMiss Rosen

Benjamin Fredrickson speaks to Another Man about chronicling his sexual awakening and seroconversion through means of his Polaroid camera

“I’ve had a curiosity about sex work since seeing films like Belle du Jour, but I was naïve – it’s totally not like that,” photographer Benjamin Fredrickson says with a knowing laugh.

After graduating from the Minneapolis College of Art & Design in 2003, Fredrickson had a run of bad luck, resulting in an injury that forced him to move back home with his parents. “I was going through a dark time, falling into a depression and feeling stuck,” he says, speaking to me from his New York studio.

In 2005, Fredrickson embarked on a course that would change his life: he became a sex worker to support himself financially. “It was out of necessity,” he says. “At that time, it felt like my best option. Sex work allowed me to afford my own apartment and shooting Polaroids. At the same time I had a day job working at a local grocery store, so it was like having a double life.”

Before the days of smartphones and easy-to-use apps, sex work required a little more footwork and time on the computer. “The internet was different then – you had to set up profiles on websites like Adam4Adam and Craigslist,” Fredrickson remembers.

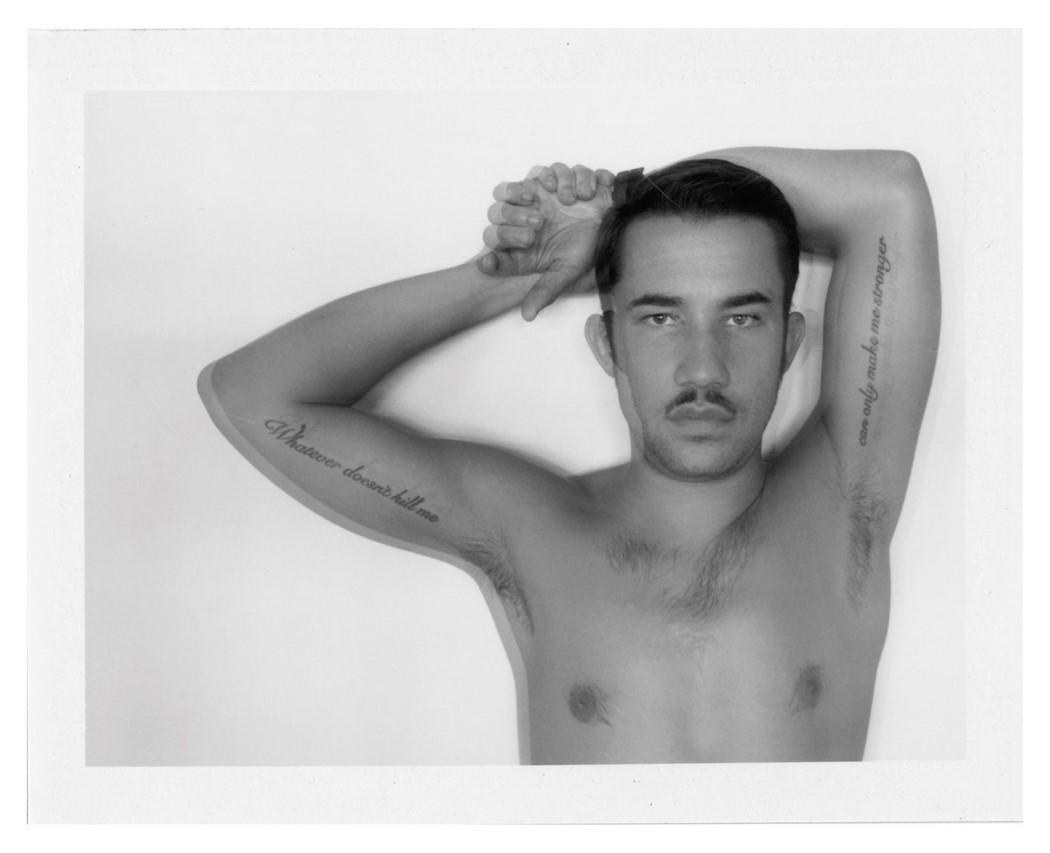

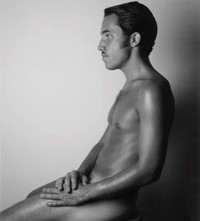

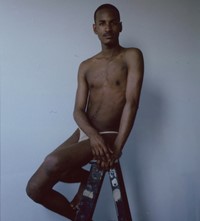

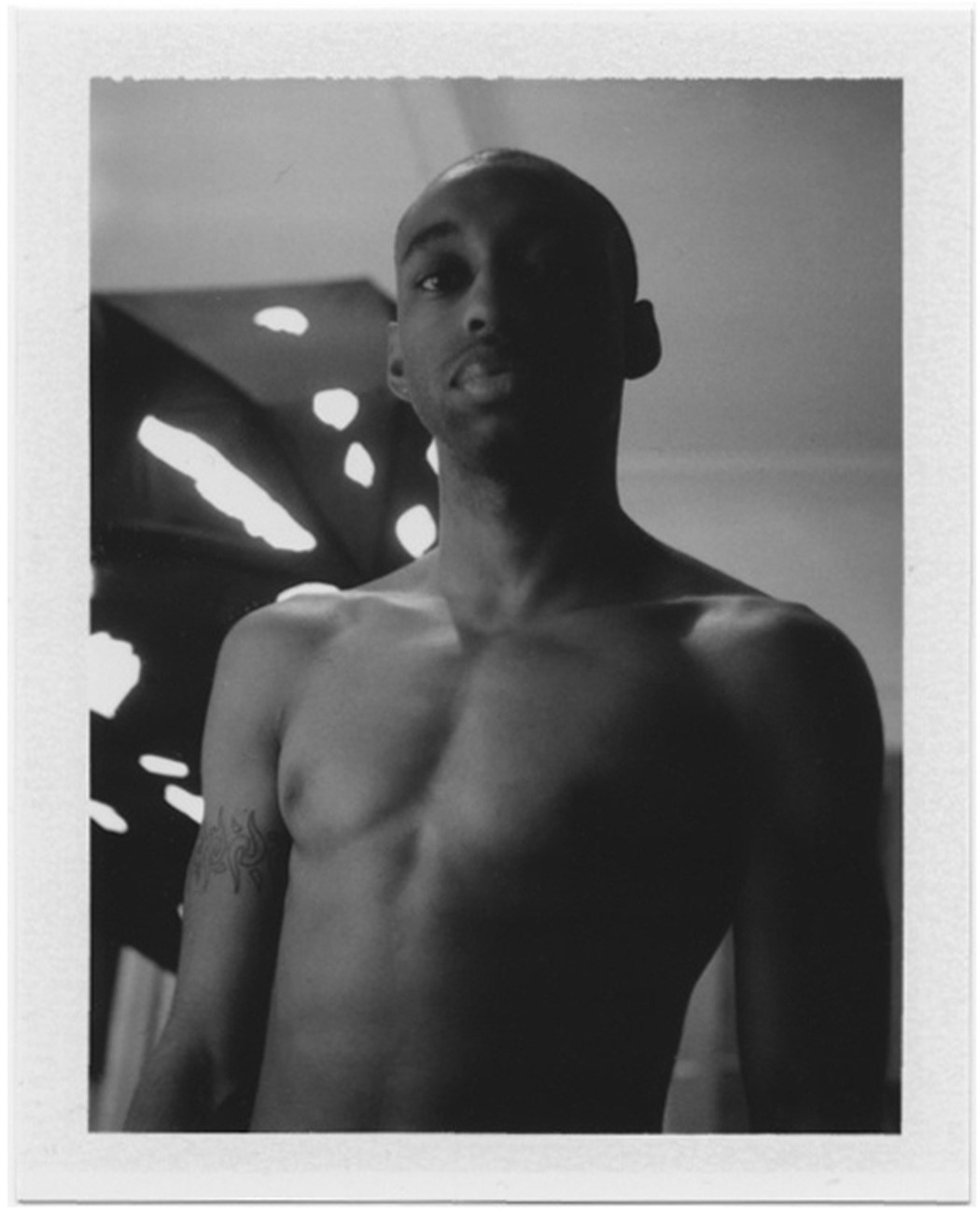

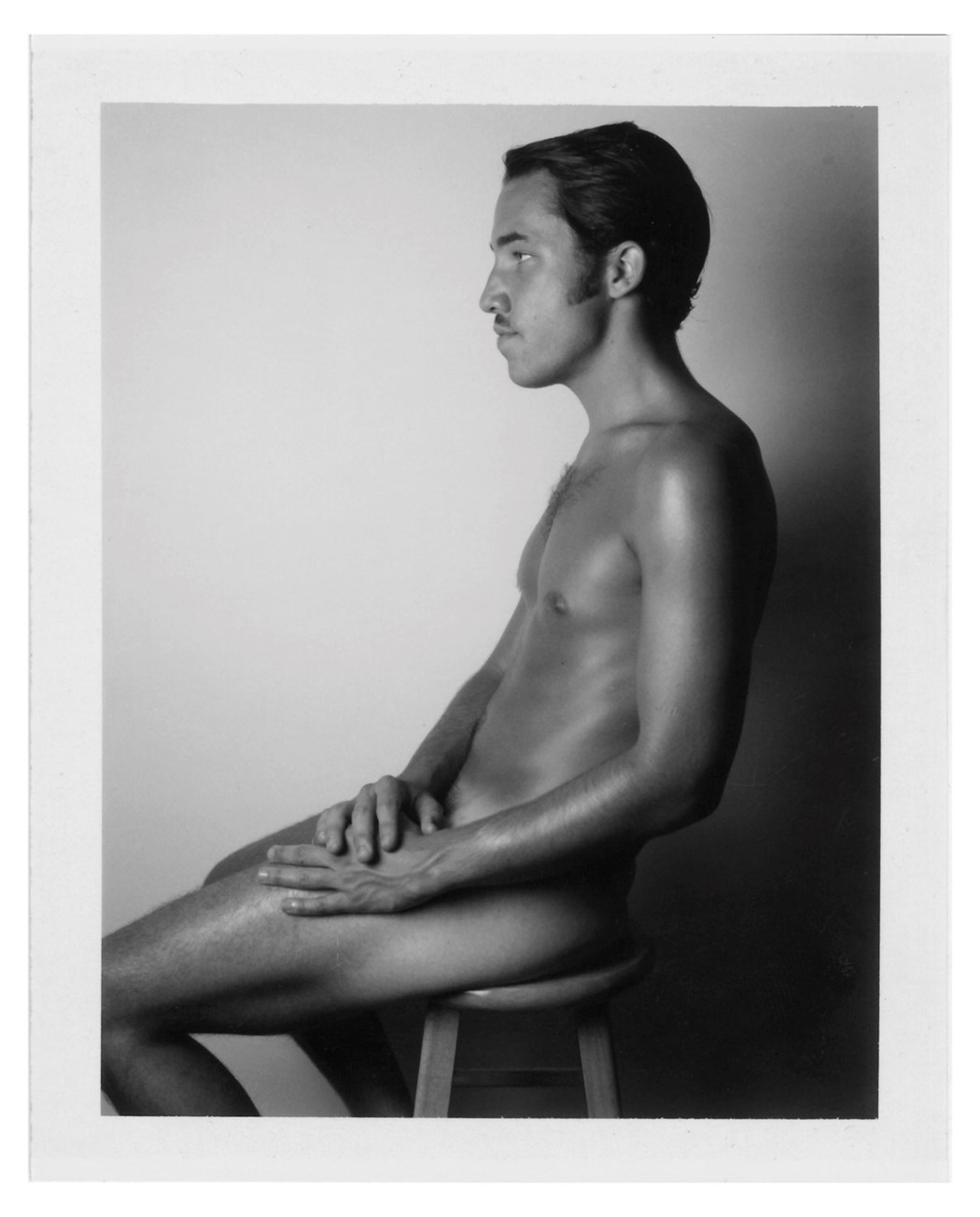

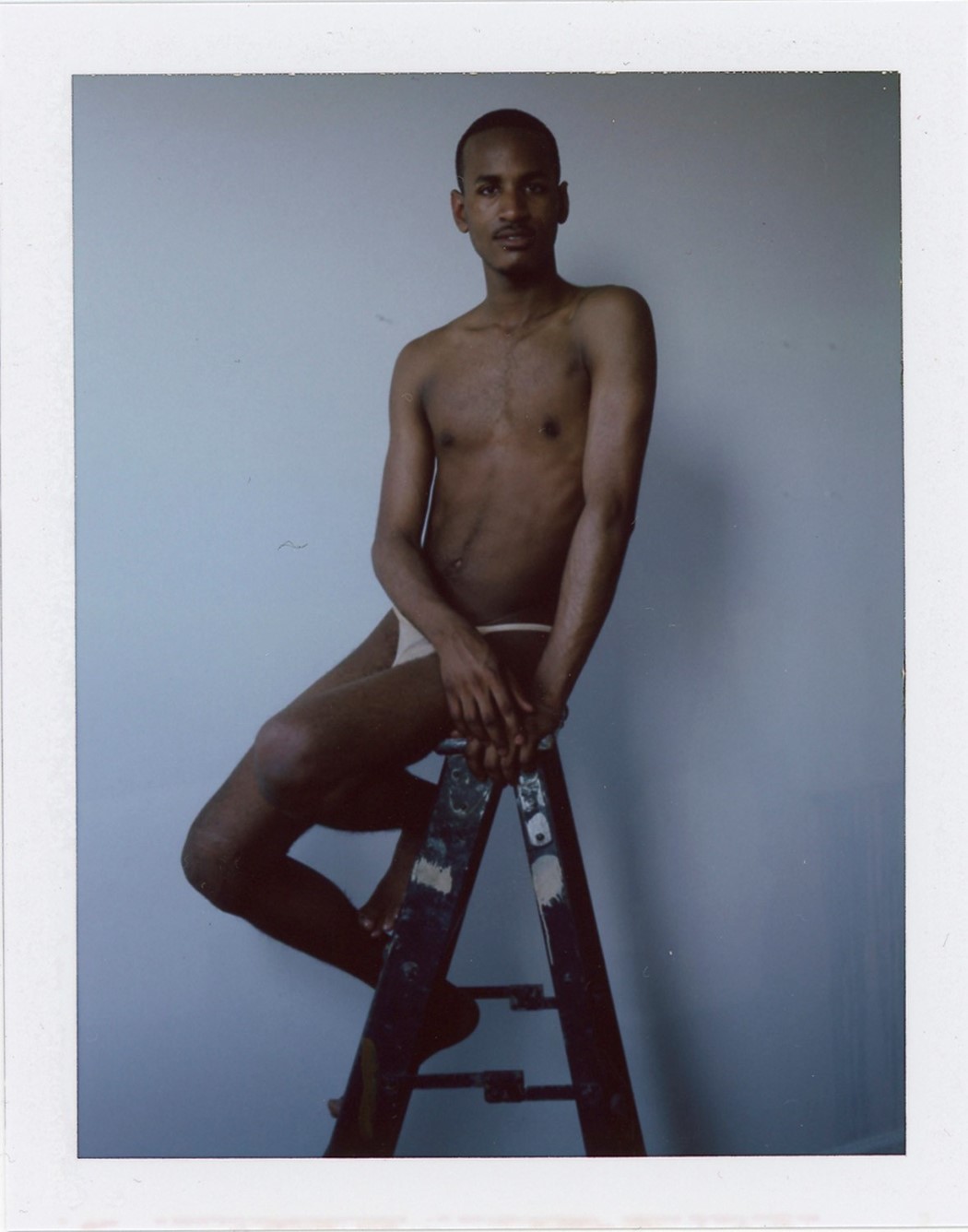

At the same time, he returned to photography, bringing a Polaroid camera to hookups and documenting this moment in his life. “I was meeting interesting people and going to different environments,” he says. “I wanted to see what it looked like and record it for memory’s sake.”

The following summer, Fredrickson experienced symptoms of the flu that he brushed off until one day, when his friend was giving him a haircut. “He noticed a lump on my neck. It was my lymph node. In September I got it checked out and that’s when I seroconverted,” he recalls.

“Not knowing who I contracted HIV from was hard for me to deal with in those early moments. I was struggling. For a while, I was drinking very heavily. I have seen people in similar situation: seroconverting and spiraling out of control. Taking that energy and putting it into something that can help others instead of destroying ourselves is hard.”

The photographer remembers the stigma attached to HIV at the time. “On websites, you would check a box marked ‘Negative,’ ‘Positive’ or ‘Don’t Know.’ Now, there isn’t a ‘Don’t Know.’ Most people are aware of their status and comfortable talking about it.”

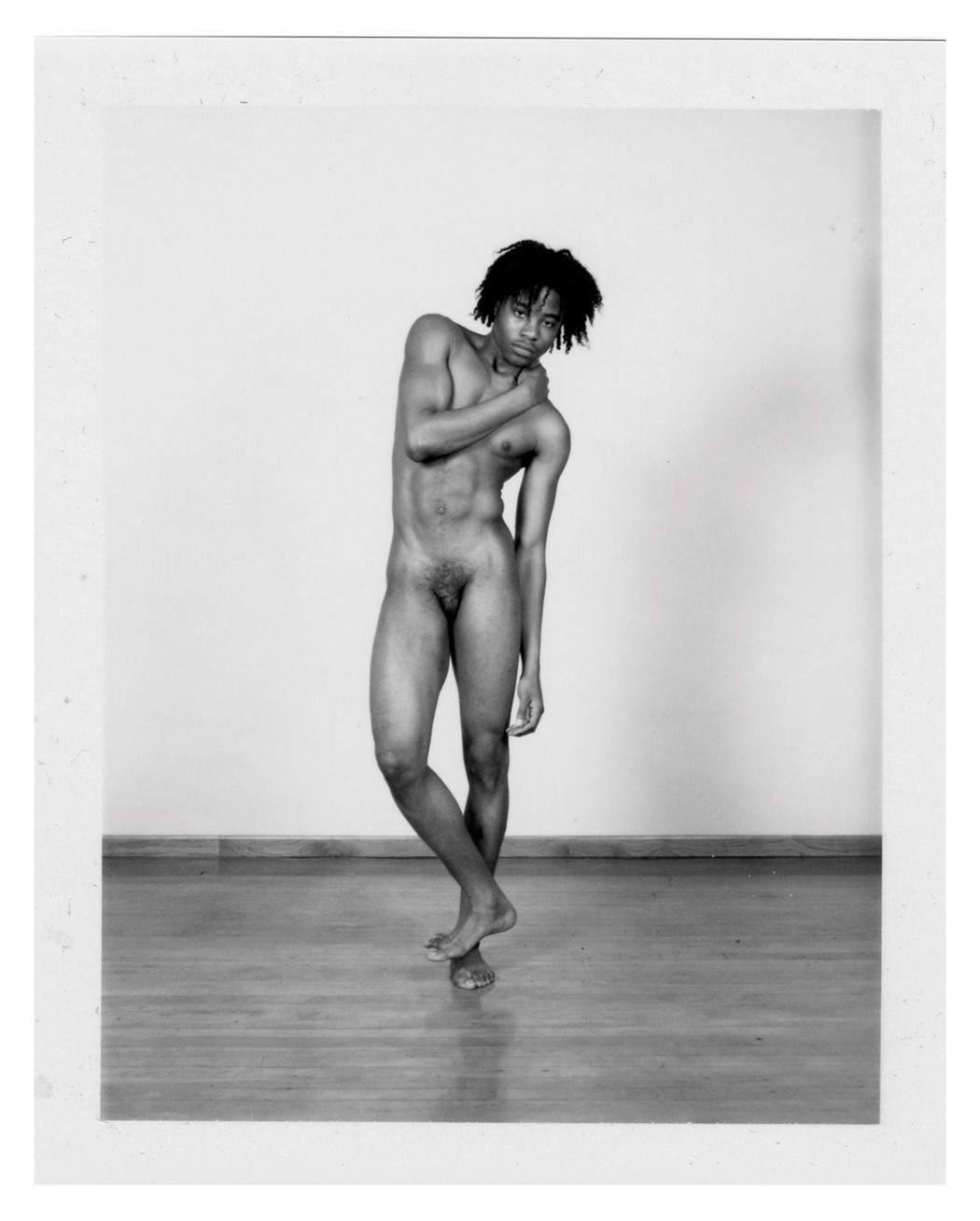

After seroconverting, photography took on deeper importance in his life. “Exploring my sexuality through my art was very therapeutic for me. The exploration of self has been important for as long as I can remember. It’s not something I can always verbalise, but visually I work through things,” he says.

“Doing photography and being upfront with people about my status was a way for me to cope because I wasn’t talking to anyone about it. It became more apparent to me that I need to make work of my friends, clients, and people in the Minneapolis queer community. I think it was out of necessity as an artist.”

Photographing clients presented a challenge. “People have other lives. This was not something they want revealed. Most clients were not into it but there were certain people who I spent time with on a consistent basis who became more comfortable with my photography,” he reveals.

Anonymity provided Fredrickson and his clients with the means, and the Polaroid camera offered the perfect mode in the days before digital photography allowed people to see instant results.

“People were more comfortable knowing their identities were hidden,” Fredrickson notes. “With the Polaroid, people could see the photograph right away. For a lot of them, this was something new. Looking back, I can see it was a strange request to them but they were able to enjoy it.”

As the series progressed, Fredrickson realised the camera could be both an erotic and therapeutic tool, allowing him to rebuild trust that was lost after being unknowingly infected by a former partner who did not know, or did not disclose.

“It was really personal for me to be able to let my guard down, and understand trust and consent. It was all an honest approach,” he says. “I wanted to feel like it was okay to be a sexual person. My status shouldn’t get in the way of me having a full sex life – and making pictures that can be seen as sexy and HIV positive, not having it seem like a bad thing.”

Fredrickson’s Polaroids, made between over the period of a decade in Minneapolis and New York, are a radical departure from the past. “It is a new day. At that time there wasn’t PrEP. When I was making this work, it was an in-between time when there was a stronger stigma attached to HIV. People were still very cautious and there was a lot more rejection around status than there is today,” he says.

His images were immediately well received. First published in Butt magazine in 2009 while the series was in progress, then exhibited upon completion at Daniel Cooney Fine Art, New York, in 2015, they reflect just how far we have come on a journey to heal, as both individuals and a society, from the ravages of AIDS.

“Today, people are more informed. It’s not a death sentence anymore. These aren’t dark times. I happened to document early in my diagnosis and there were dark moments for sure but I am so happy I am healthy today. There’s a responsibility to show that people with HIV have full lives.”