The Forgotten Artist Who Changed the Way We Look at Cats

- TextPaul Moody

Cute kittens fishing in a river, chain-smoking tabbies on the frontline and psychedelic cats dissolving into far-out fractals… Welcome to the weird and wonderful feline world of Louis Wain

Taken from the document curated by Nick Cave, featured in the A/W18 ‘Romance and Ritual’ issue of Another Man:

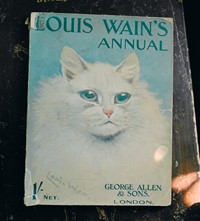

Imagine a world without Felix, Sylvester or Top Cat. Where commuters aren’t consoled by the lasagne-guzzling antics of Garfield or young girls by the trials of Hello Kitty. Where the antics of Grumpy Cat are met with a shrug rather than rapt adoration. Because all of them owe a debt of cat-itude to Louis Wain. One of the most successful and prolific artists of the Edwardian era, illustrating more than 200 books and 16 editions of LOUIS WAIN’S ANNUALS, as well as creator of cinema’s first animated feline, PUSSYFOOT, in 1917, Wain’s anthropomorphic cats did more than just delight generations of children. They helped bring them in from the cold.

“The Victorians didn’t really even like cats,” explains David Tibet at his home in Hastings. A connoisseur of outsider art, and an artist in his own right with seminal paramusical project Current 93, his fascination with Wain began as a 12-year-old growing up in Malaysia. “They saw cats, at best, as mouse catchers. By portraying cats as lovable bright and human, Wain helped change the way society looked at them.”

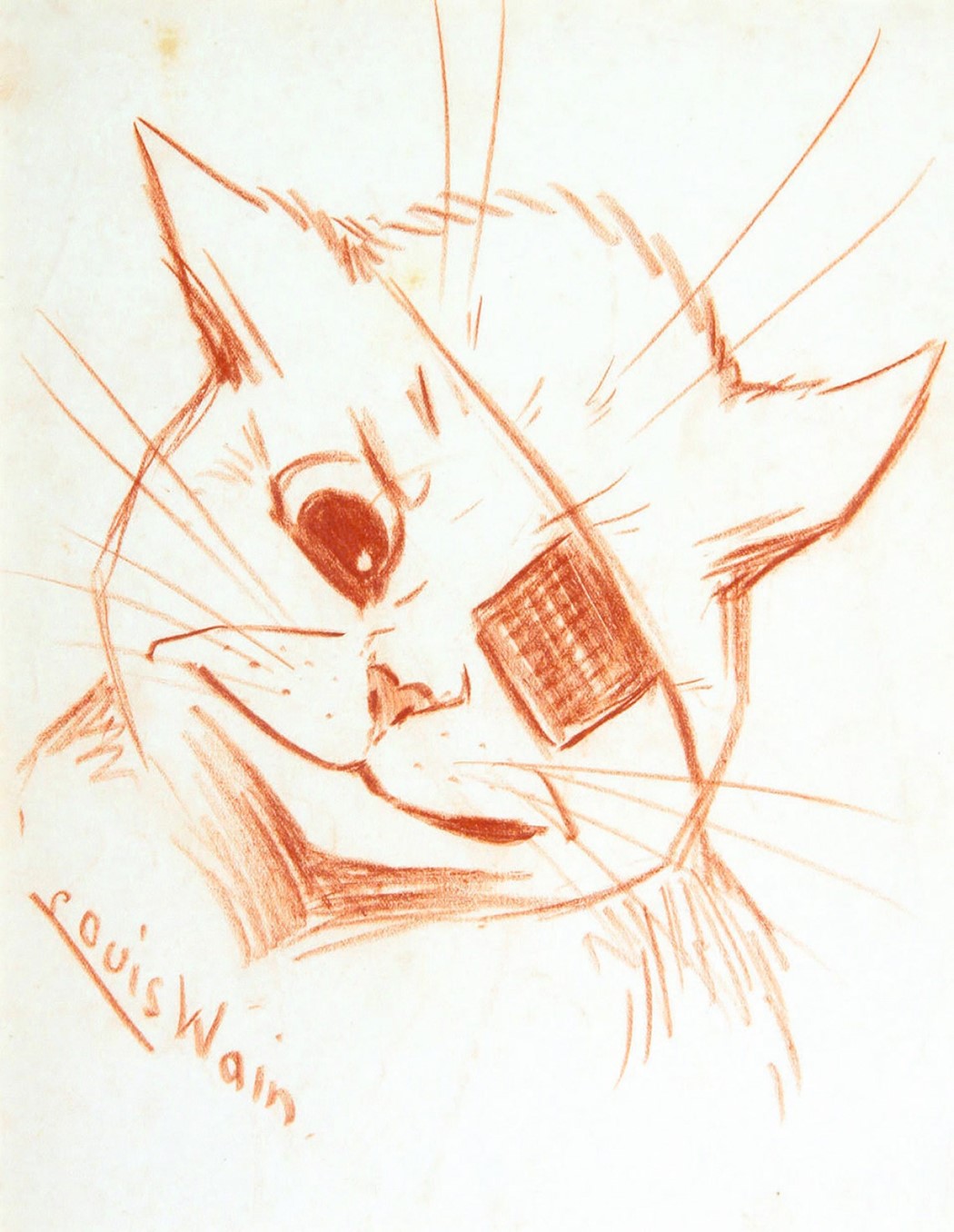

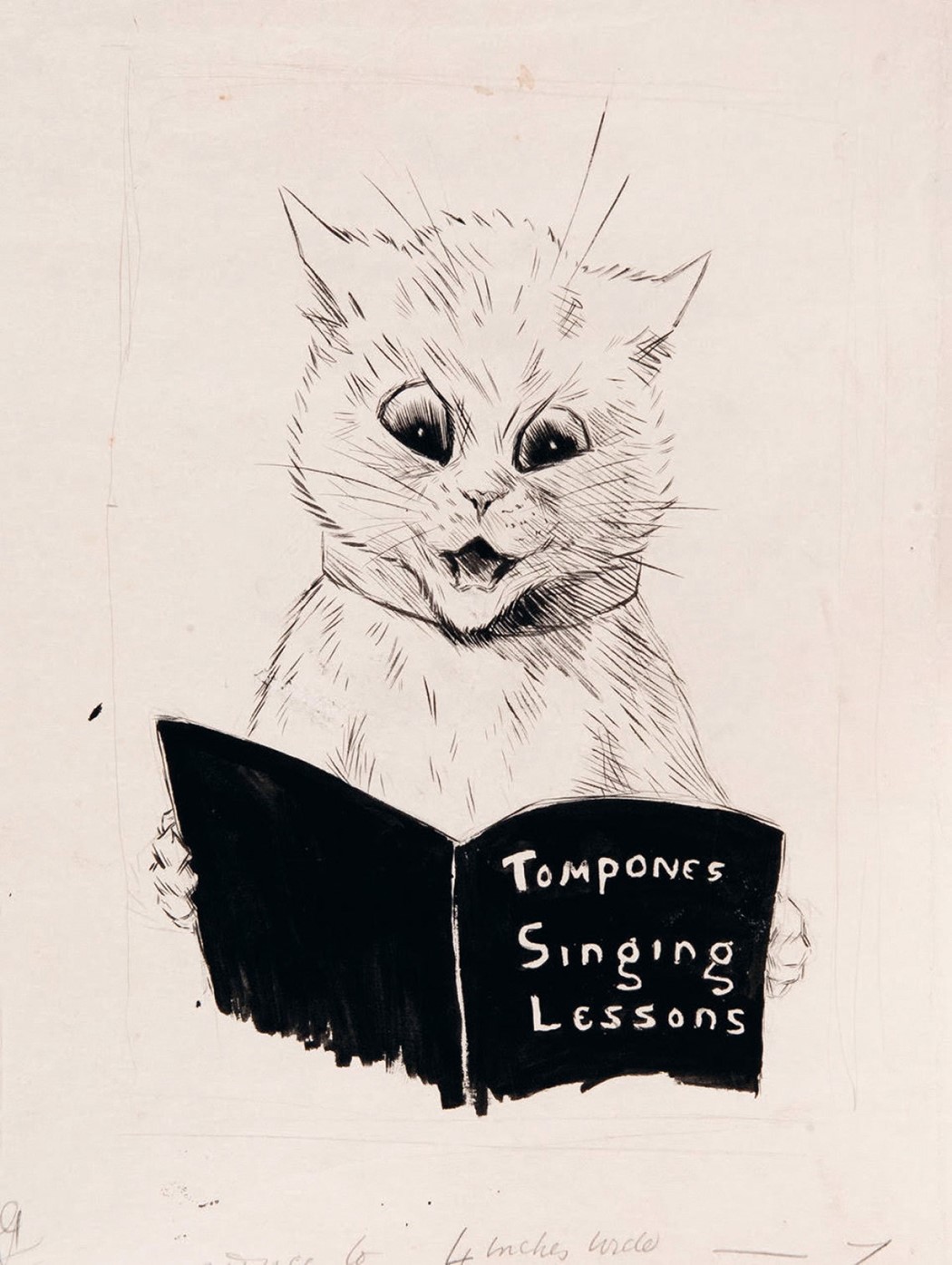

In Wain’s weird and wonderful world, tabby cats in top hats chomp on cigars and electric blue felines play violins. Others drink tea, play croquet, go to the opera, and, in some of his most striking pictures, even go to war. “He made the cat his own,” wrote H.G. Wells in 1925. “He invented a cat style, a cat society, a whole cat world. British cats that do not look and live like Louis Wain cats are ashamed of themselves.” Yet despite Wain’s undisputed genius, his name has slipped almost completely from the public memory.

Cursed, seemingly, by an endless stream of bad luck, personal misfortune and deteriorating mental health, his death a month before his 80th birthday in July 1939 came after decades of psychiatric problems which had seen him all but forgotten. “For me, Wain was pretty much a saint,” says Tibet. “As well as being a technically brilliant artist, he was a man of almost boundless generosity. He loved cats, he loved people, and he loved children. There are lots of great stories about him walking along the beach with his cats following behind him. It’s just a shame more people don’t know about him.”

The son of a working-class English textile trader and French mother born in Clerkenwell in the summer of 1860, Wain suffered from nightmares – which he later described as “visions of extraordinary complexity” – from an early age. The oldest of six children and the only boy, his sensitive disposition and hare lip meant that doctors gave orders that he shouldn’t attend school until the age of ten. A naturally gifted artist, he was eccentric even as a youth, claiming to have harnessed electricity from the ether which meant he was regularly pursued down the street by a giant ball of energy. Socially isolated, he was forced to face up to his responsibilities at 20, on the death of his father.

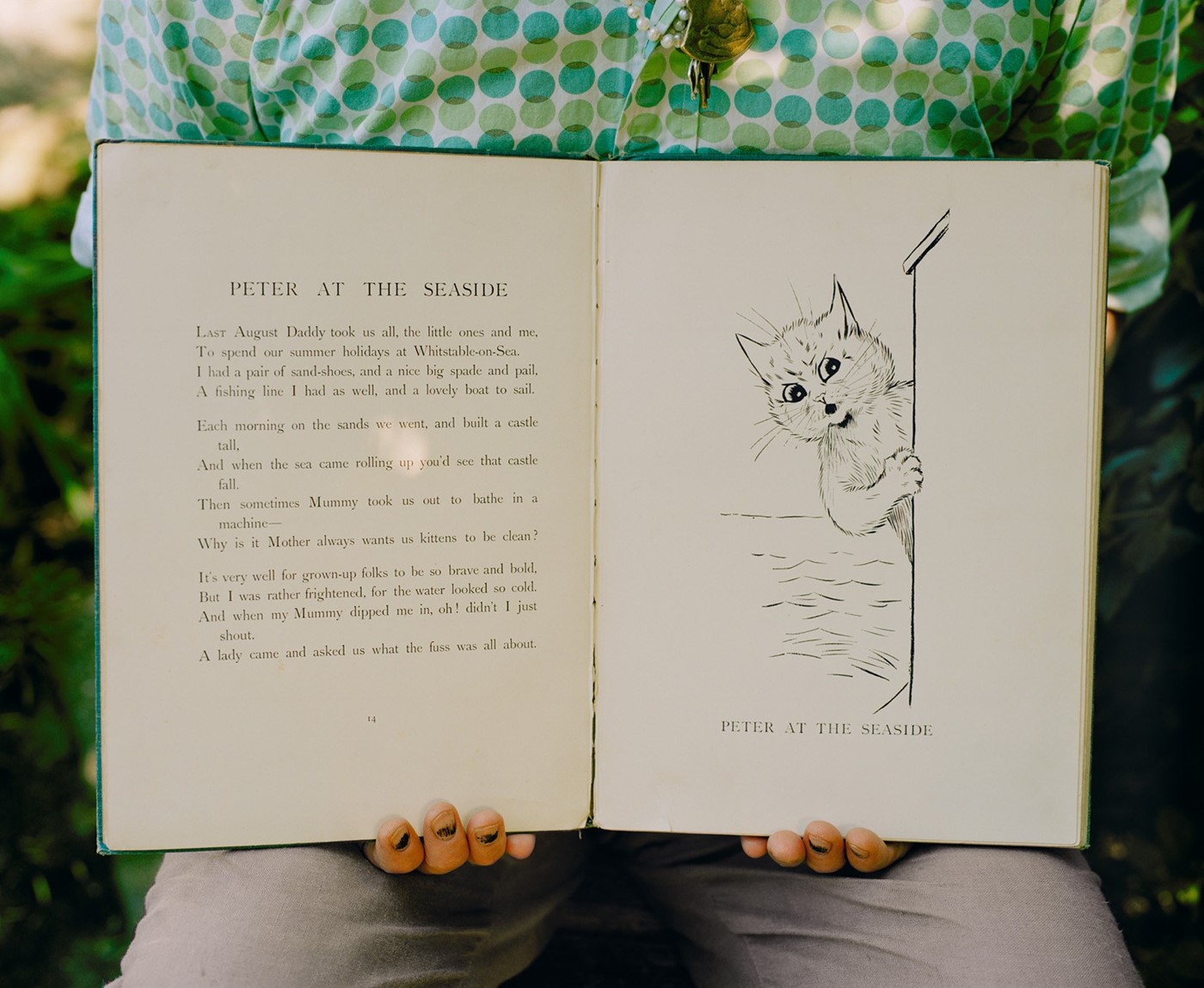

Having studied at the West London School of Art, he set out on a career as a nature illustrator, publishing his first drawing, BULLFINCHES ON THE LAURELS, in 1881. After causing a minor scandal the same year by marrying his sisters’ governess, Emily Richardson, the couple set up home in Belsize Park. However, the bad luck which would plague Wain throughout his life began when his wife became bed-ridden with breast cancer soon after. To raise Emily’s spirits, Wain started drawing light-hearted portraits of their black and white cat, Peter. Such was the delight the pictures gave her, Wain started submitting his cat drawings to publishers.

“The Victorians didn’t really even like cats. They saw cats, at best, as mouse catchers. By portraying cats as lovable bright and human, Wain helped change the way society looked at them” – David Tibet

His breakthrough came with an 1886 illustration in the Christmas edition of THE ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS. Entitled A KITTEN’S CHRISTMAS PARTY, it showed 150 cats, many of them based on Peter, preparing for the festive season, writing invitations, making speeches and playing games. The drawing caused a sensation, but Wain’s joy was short-lived.

Traumatised by his wife’s death three years into their marriage, he threw himself into his work, spending painstaking hours producing hundreds of drawings a year. Christmas 1903 alone was marked by the publication of 13 Wain books as well as countless illustrations for postcards and periodicals, each with their own descriptive text. Yet Wain’s finances remained precarious, his lack of business sense and generous nature making him an easy target for both unscrupulous business partners and begging letters.

“He was a martyr to his own kindness,” explains Tibet. “He wasn’t financially minded and didn’t keep the rights to his drawings, so he constantly had to produce more to provide for his family.” As his fame grew, Wain’s drawings became ever more elaborate. Morphing from cute and cuddly to saucer-eyed and overtly satirical, his cats wore contemporary clothes and exaggerated expressions, parodying the pursuits and pretensions of polite society. “I take a sketch-book to a restaurant, or other public place, and draw the people in their different positions as cats, getting as near to their human characteristics as possible,” said Wain of his mogg-us operandi. “This gives me doubly nature, and these studies I think to be my best humorous work.”

Christening his whimsical world ‘Catland’, Wain became the subject of fanatical interest among Edwardian audiences craving the subversive and hallucinatory after decades of buttoned-up Victorianism. His esoteric beliefs – he thought that striped tabby cats were comprised of magnets bound to the North Pole – also chimed with contemporary interest in psychology and theosophy.

“He loved cats, he loved people, and he loved children. There are lots of great stories about him walking along the beach with his cats following behind him. It’s just a shame more people don’t know about him” – David Tibet

“Wain had some really interesting ideas about vibrations coming from cats,” explains Tibet. “There’s one famous illustration called THE FIRE OF THE MIND AGITATES THE ATMOSPHERE which reflects the way he was thinking. He talks about cats transmitting energies, which isn’t a million miles from the things people like Aleister Crowley, Russian occultist Madame Blavatsky and Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner were saying at the time. He was a proto-hippy, in a way. You just have to think about Withnail and I, when Danny the Dealer says that ‘hair are your aerials’. It’s the same thing.”

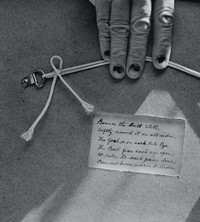

By the time of the first world war, Wain’s cats had taken on a slightly sinister edge. One of his most famous illustrations, called ENTRENCHED (A MESSAGE FROM TOMMY (C)ATKINS AT THE FRONT) features a debonair, if manic looking tabby cat with a cigarette in one paw and a rifle in the other. “At the time, that picture was published as a postcard,” explains Tibet, who once owned the original illustration. “It came with the caption: ‘Not only are soldier-cats entrenched, but safe from match-making maniacs. Hullo you Girls!’ It’s very sad and disturbing, especially when you think it might have been the last message sent home by a soldier to his girlfriend who was subsequently killed in action.”

With public attitudes changing during wartime, Wain put his energies into a series of ceramic cats. In dire financial straits thanks to a series of poor investments, it was a last roll of the commercial dice. Garishly painted and slavishly in thrall to the craze for cubism, the cats – ironically dubbed the ‘Lucky’ series – were poorly received. To make matters worse, a consignment of the ceramics bound by ship for the lucrative American market was torpedoed in the Atlantic by a German U-boat in 1915, capsizing his already precarious finances.

The prospect of having to produce yet more pictures took a heavy toll on a psyche already damaged by the death of his sister Marie in an asylum two years previously. The final straw came with the death of another sister, Caroline, in 1917. Wain became neurotic and obsessed with order, rearranging the furniture in the family’s house in Kilburn, sometimes on an hourly basis. Prone to paranoid delusions, and believing that his remaining sisters were plotting to kill him, he tried to throw one of them down the stairs before the family reluctantly had him certified insane in June 1924.

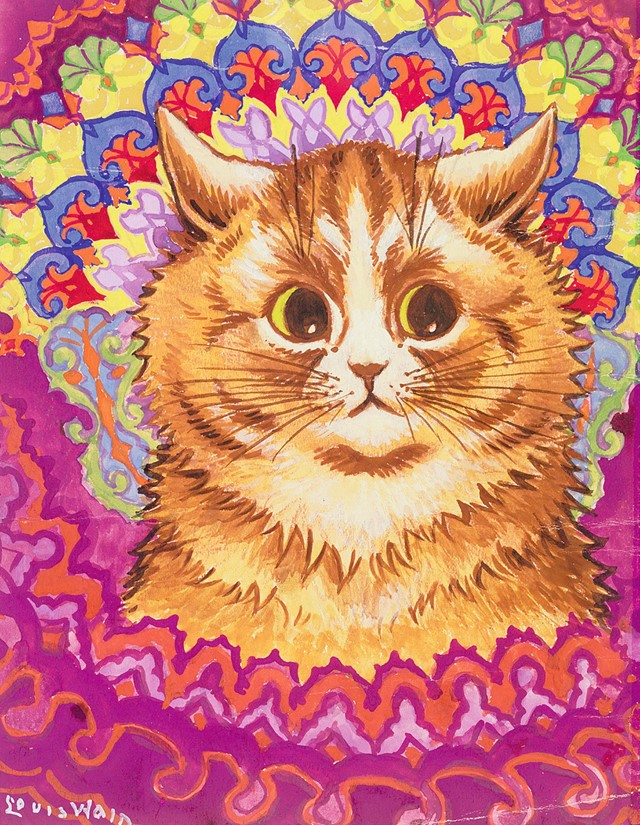

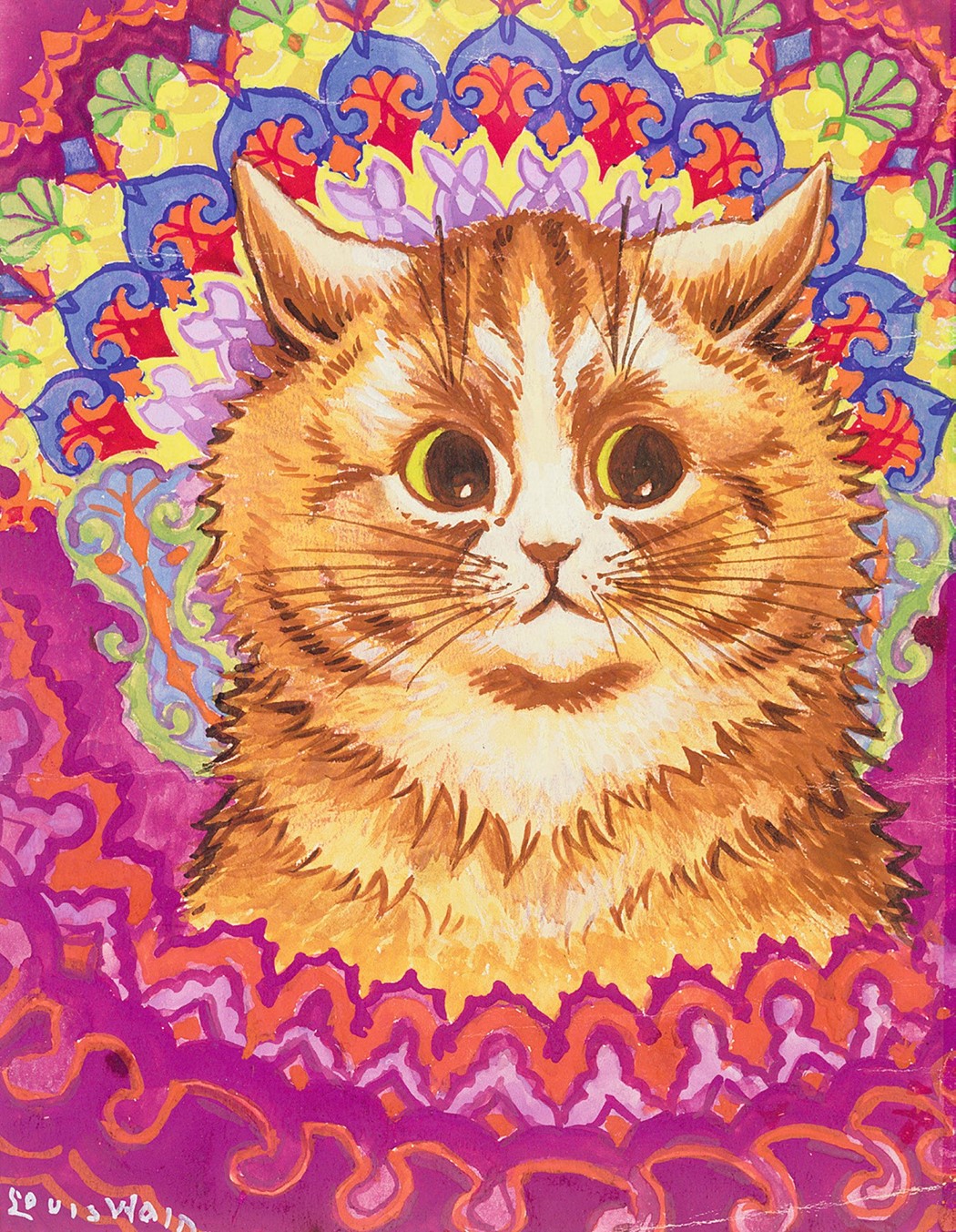

“By his final years, Wain’s cats had become kaleidoscopic, dissolving into abstract patterns resembling Hindu deities, anticipating psychedelia by decades”

Installed in the pauper ward of Springfield Hospital in Tooting, Wain’s plight only came to public attention a year later when a bookseller named Dan Rider, while visiting another patient, happened to see “a quiet little man” drawing cats. An outpouring of affection from a host of public figures including Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald saw Wain transferred to the notorious Bethlem Royal Hospital – nicknamed Bedlam – in Southwark (now the Imperial War Museum).

However, Wain’s behaviour continued to deteriorate. He refused to wash, and demanded nurses bring him a constant supply of his favourite drink, Bovril and soda. Without supervision, he would drink paraffin. It was only when he was moved to Napsbury Hospital in Hertfordshire, five years later, that any form of equilibrium returned. While still prone to delusions, its gardens and colony of cats provided the serenity Wain needed. Drawing for pleasure rather than to a deadline, his felines perked up, radiating health and vitality in drawings such as CAT CAUGHT IN A RAINBOW where only the eyes hint at his inner turmoil.

By his final years, Wain’s cats had become kaleidoscopic, dissolving into abstract patterns resembling Hindu deities, anticipating psychedelia by decades. “I love those later paintings,” says Tibet of works known as the ‘fractals’. “The foliage runs riot. Everything is turned up to the maximum. If you dropped some acid and looked at a cat, that’s what you’d see. They remind me of something that was said about another painter of the time called Charles Sims, who everyone believed had lost his mind when he started painting these extraordinary religious pieces. The writer Robert Aickman said that Sims had broken into ‘a new and terrible reality’. I think Wain had broken into a new reality. Except his involved cats.”

In the light of such brilliance it seems curious that the decades after his death saw Wain’s art corralled into a larger debate relating to mental health. This was largely due to the work of a psychiatrist called Dr Walter Maclay. Having chanced upon eight of Wain’s paintings in a Notting Hill junk shop in 1939, Maclay interpreted them as a whole, using them to illustrate the stages in a schizophrenic breakdown. This despite Wain never having been officially diagnosed with the illness or there being any evidence to prove they had been painted in such an order.

“Visionary, madman, or both, there’s no doubt he was successful in his bid to, as he put it, ‘wipe out the contempt in which the cat has been held’”

Other subsequent theories about Wain’s mental state – including that he suffered from toxoplasmosis, a disease passed on to humans from cat faeces – smack of anti-cat bias rather than medical fact. “Wain was undoubtedly suffering from some form of mental imbalance in the years before his death,” says Tibet in conclusion. “But the exact nature of it isn’t clear. Was he schizophrenic? Was he toxoplasmotic? No one knows. Whatever his condition, his art speaks for itself. I see him as a visionary. For me, he’s the William Blake of cats. His work has the same mix of being childlike, yet full of profundity and sublimity.”

It’s somehow fitting that Louis Wain’s story is, ultimately, as enigmatic as the cats he painted. Visionary, madman, or both, there’s no doubt he was successful in his bid to, as he put it, “wipe out the contempt in which the cat has been held”. His drawings continue to give pleasure to millions of fans, adorning everything from beach bags to, appropriately enough, mouse mats, while his legacy lives on in every frisky feline still to emerge from the studios of Disney and Pixar. In the world of cartoon cats, Louis Wain will always be the indisputable leader of the gang.

The A/W18 ‘Romance and Ritual’ issue of Another Man is out now. Buy a copy here.