Miroslav Tichý’s Mysterious Images of Unsuspecting Women

- TextSean OHagan

With cameras made out of cardboard tubes, underpant elastic and beer bottle tops, Miroslav Tichý captured ethereal images of unknowing women. Peeping Tom or outsider artist, the truth, discovers Sean O’Hagan, is a tragic tale of otherness

Taken from the document curated by Nick Cave, featured in the A/W18 ‘Romance and Ritual’ issue of Another Man:

“Here they come in twos and fives, happy girls I never met. with as many different happy lives, the careless creator could invent. This one brazen, this one shies Away from me, my darling pet, and I collect them up like butterflies, in my magic homemade net.” – The Collector, Nick Cave

In 1863, Charles Baudelaire published an essay entitled The Painter of Modern Life in which he created a vivid portrait of what he called the flaneur or wandering poet of the city. At a time when Paris was being rapidly redeveloped, Baudelaire suggested that the most valid aesthetic response was to become a kind of dandyish stroller, wandering aimlessly through the metropolis, observing the diversions and temptations on offer, while simultaneously remaining detached from them. He described the flaneur as a “passionate spectator”, someone who existed “at the centre of the world, and yet hidden from the world”.

One could describe the late Miroslav Tichý as a flaneur with a camera, but, as with most attempts to define him, it does not come close to capturing his otherness. From 1965 until 1985, Tichý wandered daily through the streets of his Czech hometown, Kyjov, dressed not like a dandy, but a homeless vagabond. His stained and ragged clothes, unkempt hair and straggly beard made him an object of sympathy and derision as did the primitive homemade cameras he carried. In the guise of an eccentric outsider, Tichý surreptitiously photographed the world around him, day after day, for 20 years without a thought for the results.

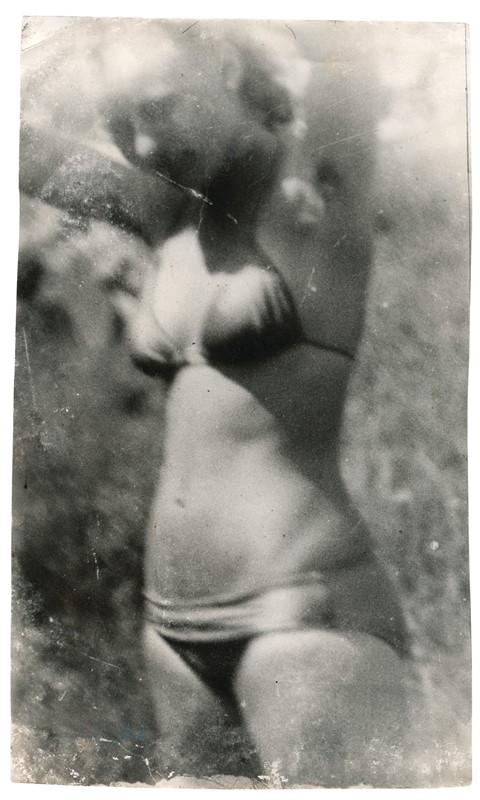

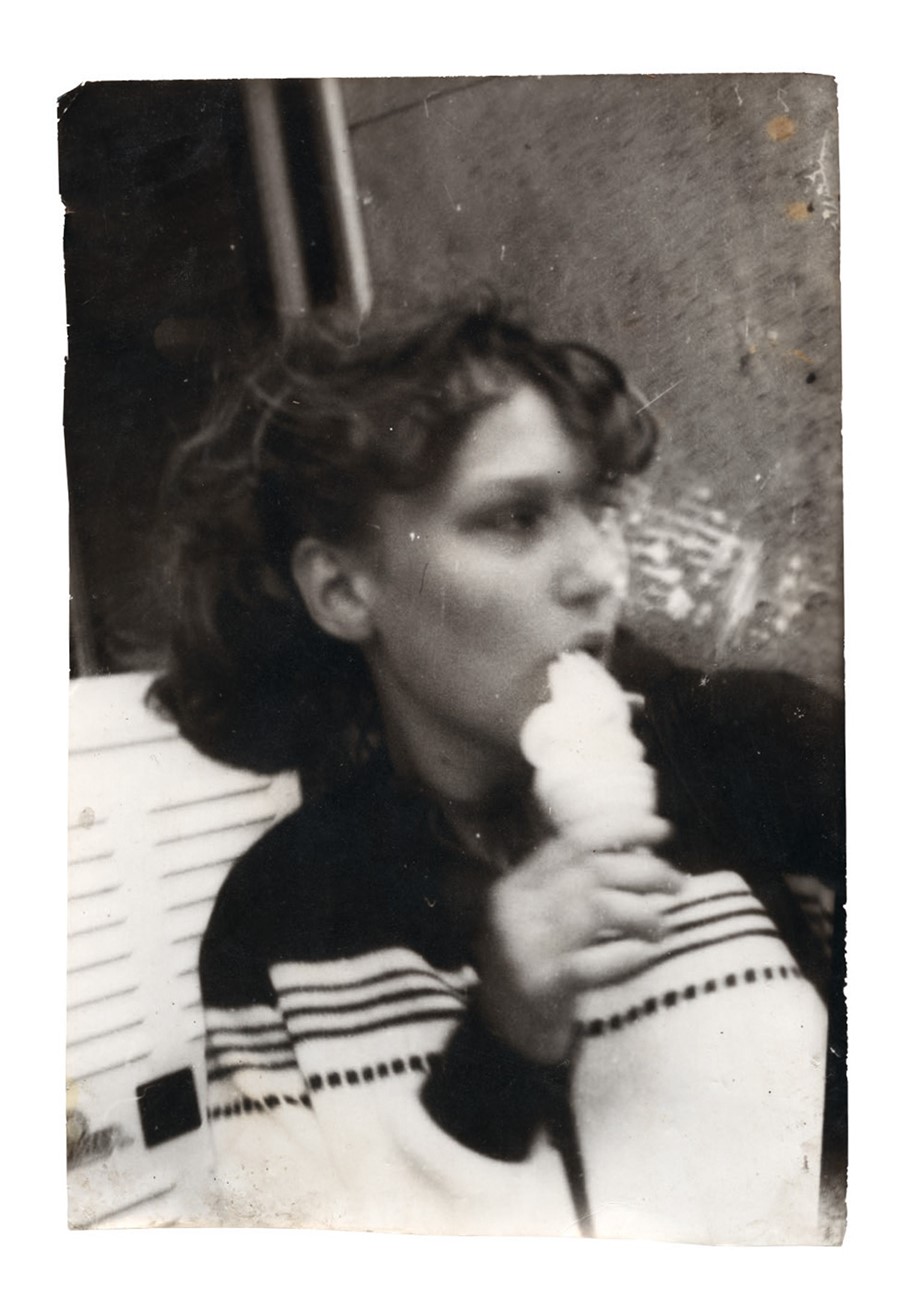

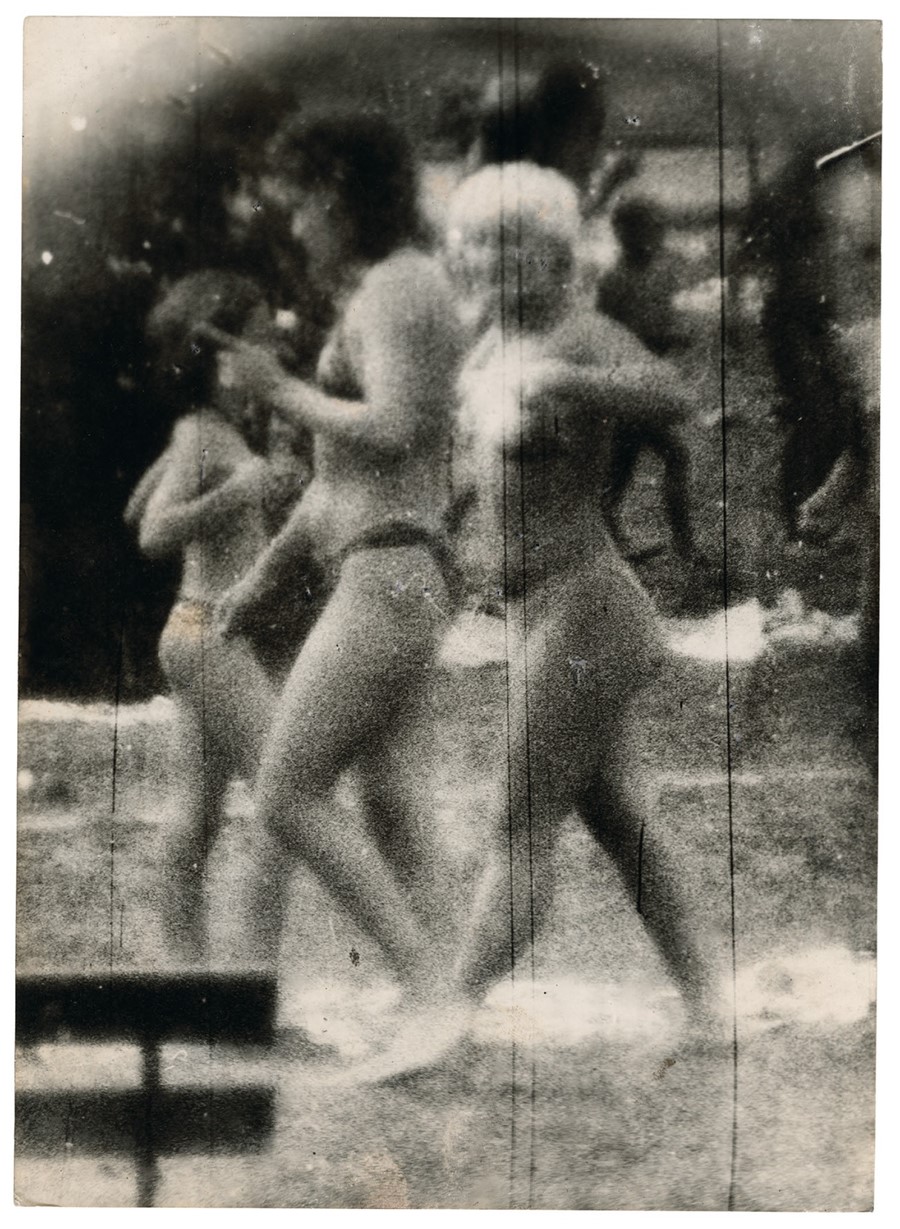

“I am an observer not only of people, but of everything,” he said later, and the 100,000 images he amassed as a passionate spectator of the everyday certainly attest to that. His abiding interest – some might say obsession – though, was the young women he photographed from a distance on the streets, in the parks and at the local public swimming pool. He mostly snapped them without their knowledge, which further complicates their uneasy erotic undertow. Writing in the New York Photo Review in 2010, R. Wayne Parsons described Tichý’s work and its tensions: “We see women photographed from the rear, from the front, from the side; we see their feet, legs, buttocks, backs, faces, as well as complete bodies… we see them walking, standing, sitting, bending over, reclining. There are a few nudes, though the poor image quality sometimes makes it difficult to determine if we are looking at a nude or a woman with not much on... Whatever eroticism is present is limited to that of the voyeur; these women are not inviting us into their world.”

For some feminist critics, Tichý’s furtive photography places him beyond the pale as a predatory male voyeur who spied on his unwitting female subjects. Others have interpreted his approach as a subversive response to the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, which abruptly curtailed the Prague Spring of artistic free expression. Tichý, one imagines, would have found both interpretations absurd. He felt compelled to photograph, but had little interest in the reasons why – or, indeed, the end results.

“Perhaps it was the actual activity of taking the photographs that was important to him, not the objects themselves,” says Nick Cave, who is a passionate admirer of Tichý’s work and has written a song, The Collector, about him. “It was the making of the photograph that compelled him to go out each day and take these thousands of photographs. I understand that very well myself. The piece of art, in my case the song, loses much of its value almost the instant it is fully realised.”

“Perhaps it was the actual activity of taking the photographs that was important to him, not the objects themselves” – Nick Cave

Having been introduced to Tichý’s work in 2007 by the photographer Polly Borland, Nick Cave now has 11 original prints. “They are,” he says, “the most beautiful things I own.” I ask him if he can cast light on their particular mystery. “As a person with voyeuristic tendencies myself, in the sense that I get great pleasure out of watching things, especially people, I love the way Tichý makes something almost religious out of women’s unconscious selves. They seem to me to be devotional images, snatched moments of ordinary transcendence. I find a similar thing in Auguste Renoir’s quietly exquisite paintings of women absorbed in some simple, unremarkable activity.”

It turns out that Cave takes photographs too, mainly of his wife, the model-turned-designer Susie Bick. “The best ones are the ones where she is lost in her work, whatever that may be and doesn’t know she is being watched. From my observation, there is something in that loss of self that is close to the divine.”

Tichý’s moments of ordinary transcendence are made all the more wondrous by the fact that they were achieved using cameras he constructed at home from salvaged materials. The lenses were made from ground plexiglass, which he polished with a mixture of toothpaste and ashes; the shutter mechanisms comprised wooden spools and ribbons of elastic taken from underpants he had discarded when they became too threadbare to wear. In Tarzan Retired, a short documentary on Tichý directed by Roman Buxbaum, a former neighbour who discovered the photographer’s vast archive in 1981, Tichý picks up a blurred and grimy photograph of a woman, which was taken through the wire fence of the local swimming pool. “To achieve that,” he says, laughing, “you need first of all a bad camera.”

In another scene, he roots through a pile of discarded cardboard boxes, extracting telephoto lenses made from cardboard tubes taped together and camera winders made from beer bottle tops. His darkroom practice involved leaving the prints in water for days, before hanging them outside on a washing line. Once he had perused them, they were cast aside or stacked in piles to gather dust. The neglect, he acknowledges at one point, is part of the power of the images and somehow enhances their strange, slightly ominous, atmosphere.

“All the paintings have already been painted… what is left for me to do?” – Miroslav Tichý

In 2005, when he was 78 years old, Tichý won the New Discovery Award at the Arles Photography Festival. Since then, he has been repositioned as an outsider artist and the images that lay for so long gathering dust and grime in his hovel are now coveted by collectors. In 2008, he had a retrospective at the Pompidou Centre in Paris and, in 2010, a solo show at the International Centre for Photography in New York, which included two vitrines housing his battered homemade cameras and lamps as well as piles of dirt-encrusted prints and several rolls of still-undeveloped film. Until his death in 2011, aged 84, Tichý remained blithely unconcerned by his late canonisation by the art world, remaining a semi-reclusive figure amid the clutter of his dirty, mice-infested apartment, drinking cheap Czech beer and rejecting all artistic claims made on his behalf. When asked about his belated recognition, he replied, “If you want to be famous, you must do something more badly than anyone else in the entire world.”

Tichý’s outsider artist status, though, belies his background, which included a student apprenticeship at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague followed by a period of considerable critical and commercial acclaim as a figurative painter. In Tarzan Retired, he claims to have forsaken fine art in the early 70s because, as he puts it, “All the paintings have already been painted… what is left for me to do?”

The truth is more complex and more disturbing. In the Soviet era, Czech art students were instructed to produce heroic Socialist-style paintings exalting the workers and the leaders. Tichý rebelled by walking out of the Academy. After completing his compulsory military service, he began working in his studio, almost immediately drawing the attention of the authorities who placed him under surveillance. Soon afterwards, he was arrested and spent almost a year in prison, before being transferred to a state psychiatric clinic. The incarceration had a profound and lasting impact on Tichý’s personality. When asked by Buxbaum if he had erotic relationships with women when he was younger, he falls silent and then replies, “Erotic relationships? That always means police, prison and mental institutions.”

In 1968, following the Soviet invasion, Tichý was evicted from his studio and his paintings and drawings were thrown into the street. “I looked for new media,” he said later, “with the help of photography I saw everything in a new light. It was a new world.” The sense of a hidden world made manifest is there in Tichý’s photographs, not just in their essentially clandestine aspect, but in the atmosphere they evoke: a sense of a floating world where nothing is solid, everything is elusive. Photography is the art of stilling time, but it is also, by its very nature, a medium haunted by time’s inexorable passing – an essentially melancholy record of fleeting moments, remnants and traces. In Tichý’s work, the passage of time is actually physically imprinted on the images in their soiled and grimy materiality: the water damage, the creases, the blemishes, the dust and the dirt. They are evidence too of his outsider’s existence.

“There is, in [Tichý’s photographs], an acute understanding of the human condition as some sort of collective dream and a sense of the essential and pure moments that make up the common experience” – Nick Cave

The women Tichý collected on camera are beyond his reach, not just sexually but socially. He was banished from their realm by his otherness and made himself even more so by the surreptitious nature of his artistic pursuit and by his unkempt appearance. Children were scared of him, neighbours at best tolerant of his extreme otherness, young women repulsed by it. All this bleeds into his art: the longing, the distance, the unconsummated desire, the compulsion to photograph, to collect and then to degrade, but never fully destroy, his images. And, in spite of all this, in spite of himself, his gaze was transformative.

“Tichý was actually physically excluded from his subject’s world,” elaborates Cave. “He was not allowed, for instance, into the public swimming pool because he was seen as essentially a homeless person and therefore had to photograph the women through a cyclone wire fence. That sets up all sorts of strange tensions in his photographs – of exclusion, loneliness, obsession, alienation and exile and, of course, intrusion. But there is, in them, an acute understanding of the human condition as some sort of collective dream and a sense of the essential and pure moments that make up the common experience.”

The A/W18 ‘Romance and Ritual’ issue of Another Man is out now. Buy a copy here.