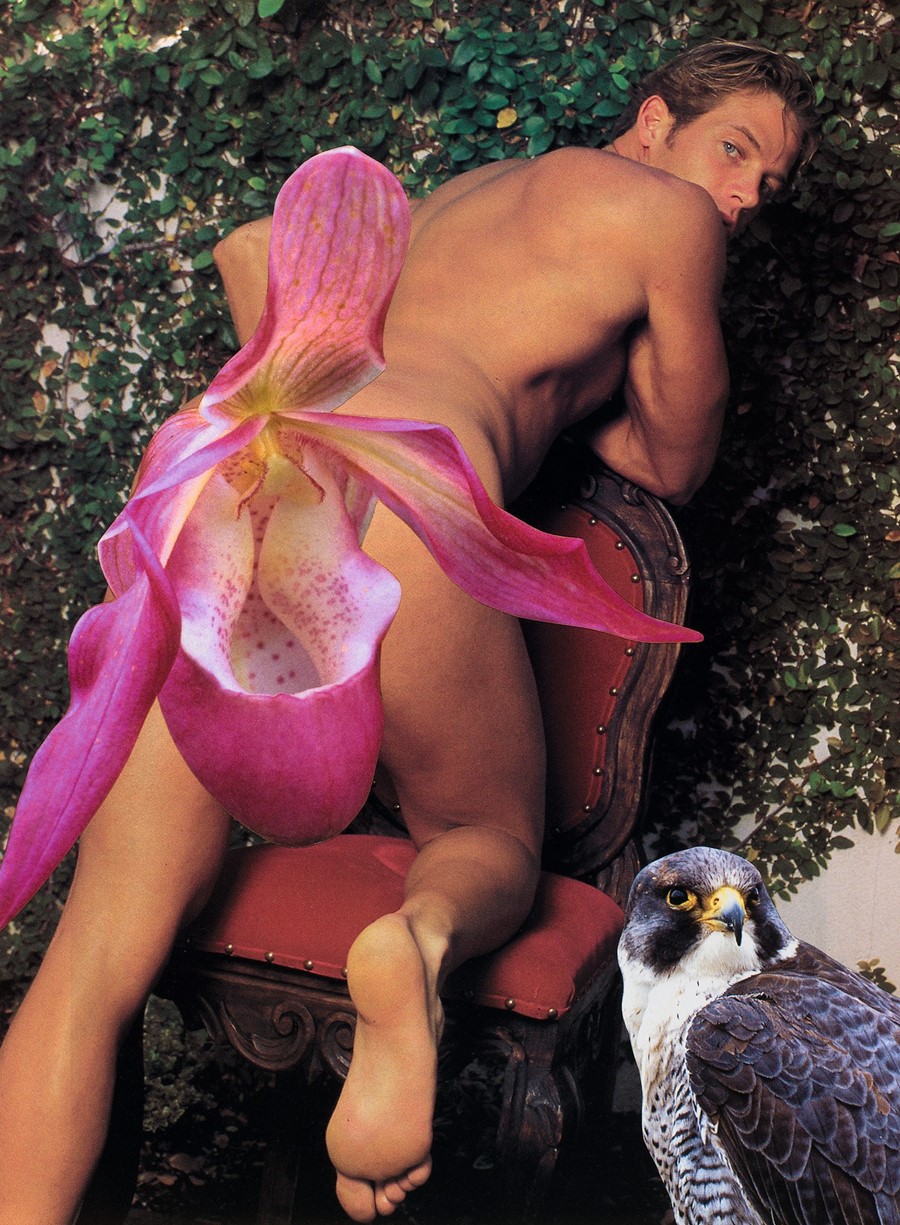

Punk Artist Linder Sterling’s Erotic Masterpieces

- TextFrancesca Gavin

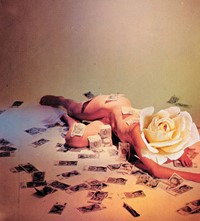

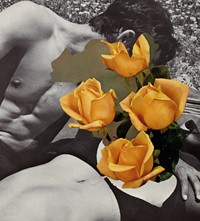

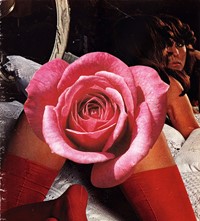

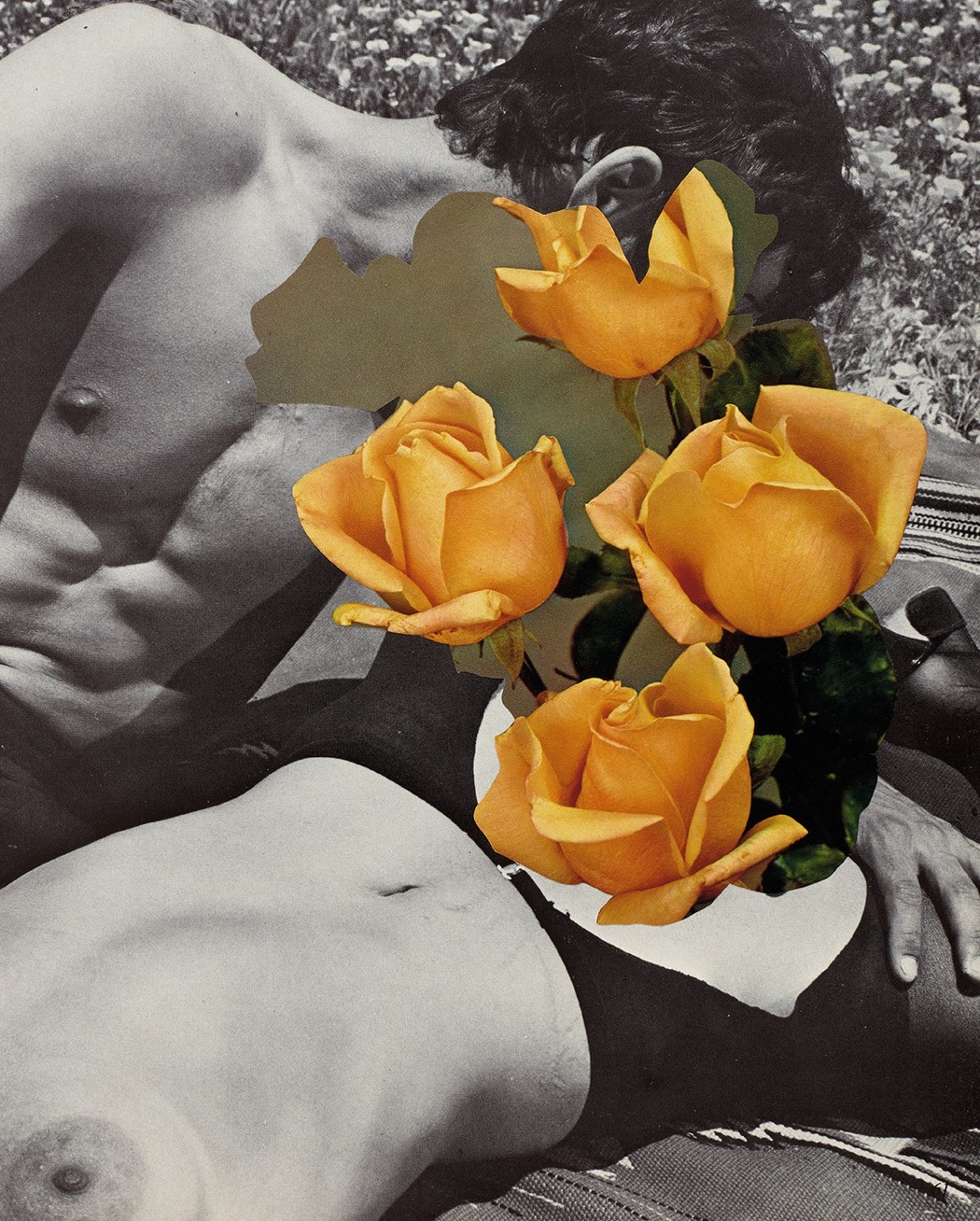

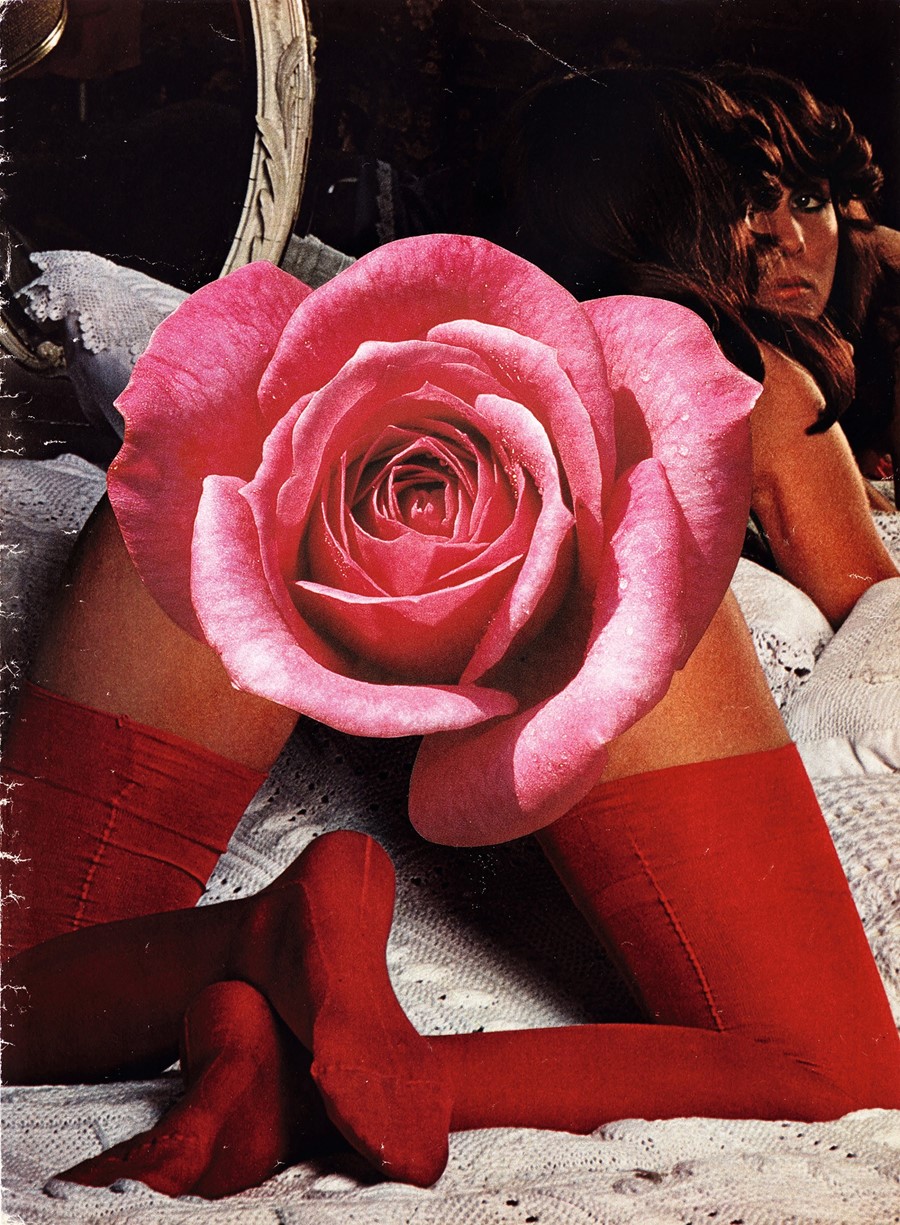

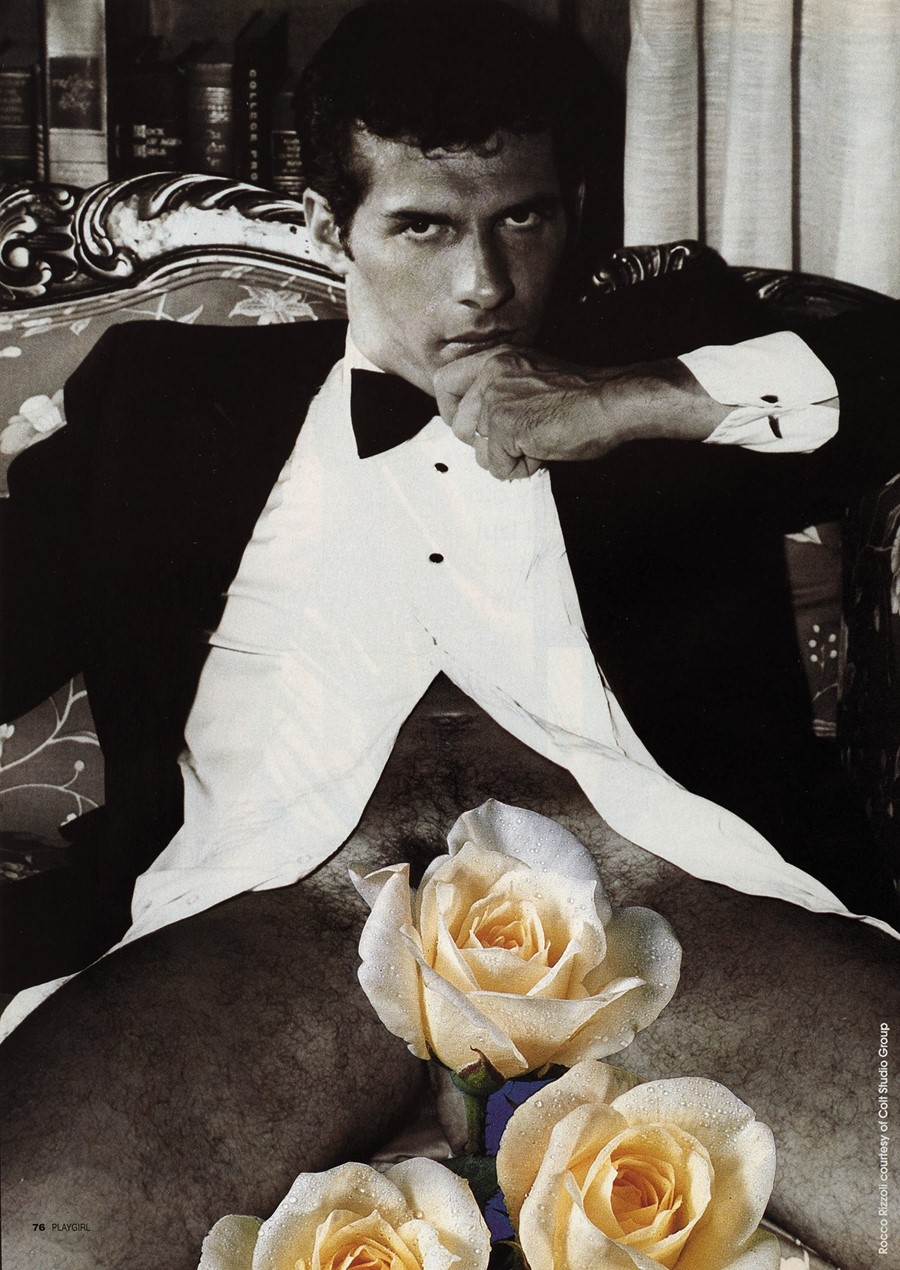

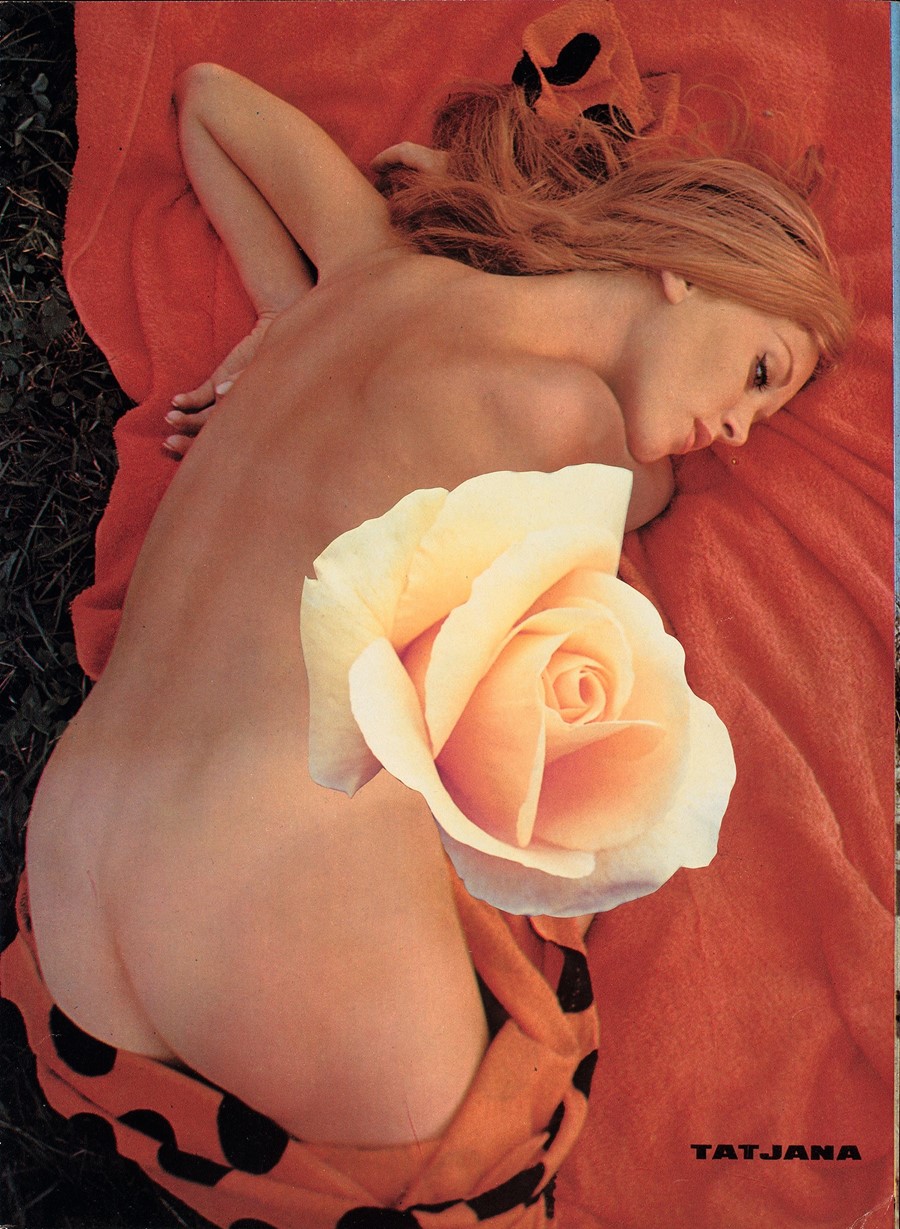

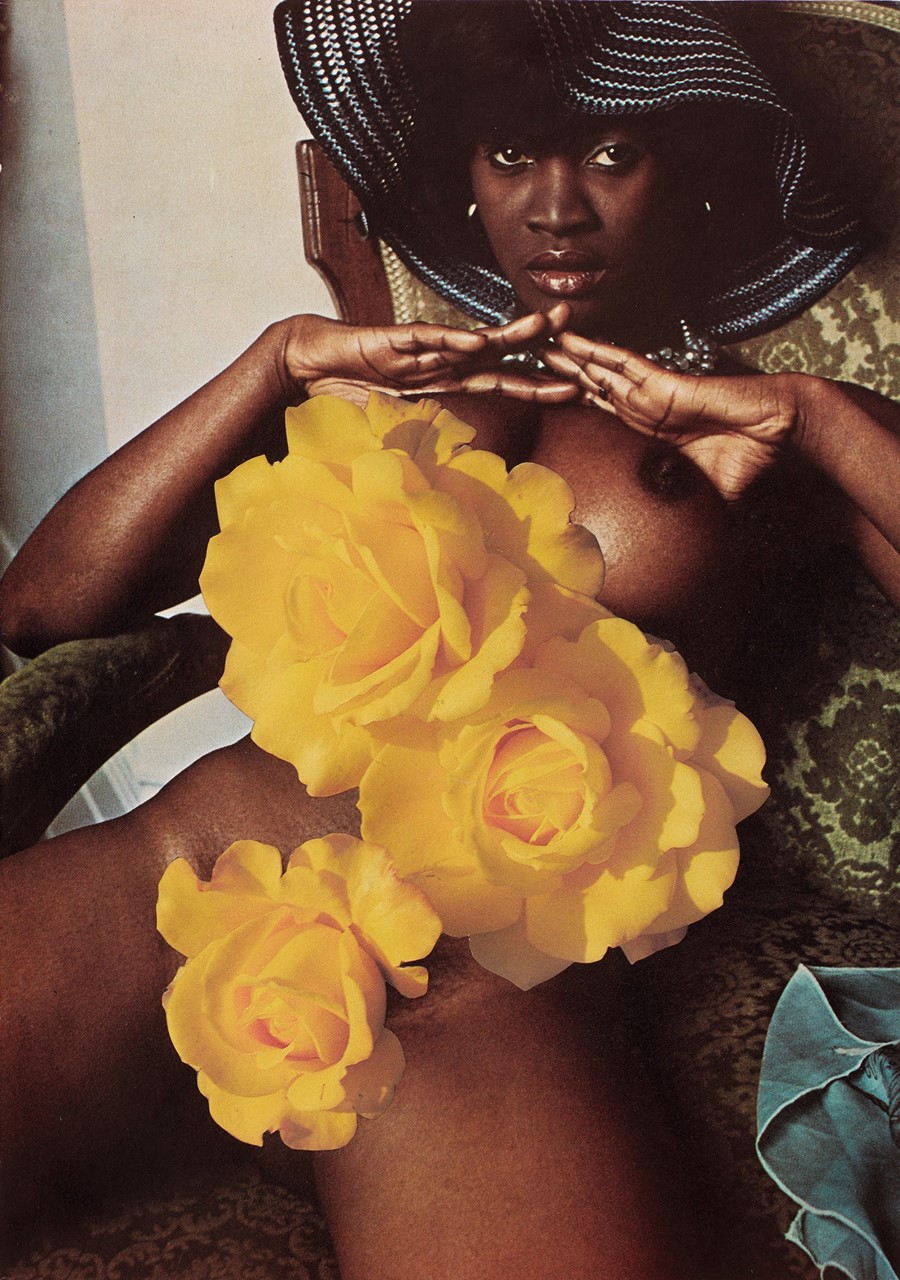

Feminist punk provocateur Linder Sterling sliced porn magazines and shopping catalogues into explosive montages attacking the patriarchy of 70s England. Here, the legendary collage artist looks back at the transformative scene that spawned her

Taken from the A/W18 ‘Romance and Ritual’ issue of Another Man:

It is an image that bites. An acid-yellow seven-inch record depicting a hard-bodied, naked female torso with an Argos catalogue iron for a head and two toothy smiles for nipples. When Buzzcocks released their single Orgasm Addict in 1977, the cover created an immediate reaction. The BBC banned the single; United Artists refused to press it. It was a reaction Linder Sterling, the creator of the artwork, became accustomed to. For 40 years her work has inspired shock and fascination, repulsion and attraction. Beneath it all is a strong sense of feminism and true innovation.

When we meet at her studio on The Cut in London, Sterling – wearing a t-shirt from the Glasgow Women’s Library, trainers and long straight hair – is an engaging and enthusiastic figure. Pornography is one of the most recognisable, signature motifs in her work; she was one of the first artists to take porn, often in its most brutal, confrontational form, and use it as material. She says she was first drawn to that imagery as a teenager growing up in a small mining village in the northwest of England: “In the October of 1970 Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch was published. I knew Germaine Greer as a comedienne on TV every Wednesday on a show called Nice Time, being very, very funny and very, very clever with Kenny Everett. As I read that book, I mean it’s cliché, but it completely rewired my brain,” she remembers. “I read it one hand turning, one hand in a dictionary, because a lot of the vocabulary was way, way beyond me at 16. It was an education in itself.”

“For me it was quite forensic. I’d read John Berger’s Ways of Seeing and things like that. They got me aware of how these images were so carefully constructed” – Linder Sterling

Diving headfirst into the literature of second wave feminism, she simultaneously became very curious about pornographic images. “I hadn’t seen any. As a young woman going off to study in Manchester, I think there were only two sex shops anyway,” she says. “For me it was quite forensic. I’d read John Berger’s Ways of Seeing and things like that. They got me aware of how these images were so carefully constructed.” People presumed Sterling was a man; she had changed the spelling of her name (Linda) in response to German Dadaist artist John Heartfield, who Anglicised the spelling of his name in protest against the prevailing politics in Germany. Although she helped to invent the aesthetics of punk, she was not really aware of how her work was received or resonated. “It was hard to gauge pre-internet,” she says. “I didn’t have a phone. Never knew my address. It was immeasurable. You’re putting work out, but you have no idea where it goes. Does it go beyond that city? Is it escaping the land you live in?” That lack of awareness gave her freedom, beyond a consciousness of its reception.

Sterling was part of a whole creative underground in Manchester. She studied graphic design at Manchester Polytechnic, encouraged by great teachers and the imagery, energy and discourse emerging from its crossover with music. The idea of images as a form of communication still comes across in her practice. She remains good friends with Morrissey, made zines with punk writer Jon Savage, and shared a flat with Buzzcocks frontman Howard Devoto. When Devoto invited her to create that iconic cover of the band’s first single, the city was in decay: “Everybody I knew was unemployable – an intelligent creative circle of people, but totally unemployable,” she says. “Manchester and Salford were not quite ghost cities, but they were culturally bankrupt, redundant. There was nothing happening.” What became known as punk filled that gap.

“I suppose the photographers who were working in the 1970s and 80s had a certain level of craft... Now, technically, you have that loss of composition, tonal balance – all kinds of formal qualities. Now I think the pornographic image has been liberated from the narrative” – Linder Sterling

Sterling formed the band Ludus in 1978. “I think for a certain time the space between being in the audience and being on stage was sort of permeable. Everybody I knew was either singing, playing guitar, bass guitar, drums. I began to think about making sounds with my larynx in much the same way, I guess, one makes sounds with images. I just began to look around for quite a conventional bass player, drummer, guitarist, and found everybody within about a week.” Notoriously, she was the first person to create a stage costume out of old scraps of meat (prefiguring Lady Gaga by decades), and she read a list of Victorian poetic slang for ‘female’ during her live John Peel session on BBC radio, calling it Vagina Gratitude. The band disbanded in 1984, but Sterling continued to make art; she now exhibits with respected galleries such as Stuart Shave Modern Art in London and Blum & Poe in Los Angeles, and recently became the first artist-in-residence at Chatsworth House, where she is currently designing a permanent “vulval garden”. Last spring she was given a well-deserved retrospective at Nottingham Contemporary.

Sterling still works with porn, though she’s aware the digital era is degrading the skill of image construction. “I suppose the photographers who were working in the 1970s and 80s had a certain level of craft. Photos were well-lit, they were exposed properly. Now, technically, you have that loss of composition, tonal balance – all kinds of formal qualities. Now I think the pornographic image has been liberated from the narrative.” Porn is just part of her huge collection of print media that she uses as source material. “I’m always looking wherever I go – to some tiny village on the northwest coast or whatever. I keep an eye open for interesting media,” she explains. An increasing consumerism is also influencing images in publications from Vogue to Playboy, she says: “It’s the brutality of the digital camera. Whether it’s bodies or cupcakes, everything is kind of pumped up. Breasts are pumped up. Buttocks pumped up.”

“You get that kind of click when images suddenly connect. It’s almost like fighting to breathe and then it’s like, OK” – Linder Sterling

Her work can feel almost violent. Images of bodies are sliced, diced and reconfigured with oversized lips, giant cutlery and items from old shopping catalogues. Faces are often covered by anything from flowers to a 70s hi-fi : “I suppose the ambiguity around the defacing of it is actually masking and granting anonymity,” she considers. It’s the immediacy that makes Sterling’s work so vital and lasting. You don’t need to give a toss about art to connect to giant banal roses juxtaposed with racy nudes and, although much of her material is vintage, its humour, narrative and provocation feels timeless.

This autumn she is working on a big project with Art on the Underground, designing a cover of the London tube map which will be printed 12 million times, as well as creating collage art on an evolving group of billboards at Southwark station. “It’s very, very ambitious,” she says enthusiastically. “The station will become this huge sticker book.” She will also enact a collaborative dance and music performance at midnight on 9th November, inspired by Mozart’s The Magic Flute – she’s worked on collaborative performances before, imagining the narrative behind an image and how her ‘characters’ would move, dress, interact and emerge from the page, “a kind of all-thinking, all-dancing collage”.

But whatever the project, everything starts with cutting out bodies on glass, playing with imagery lightly until she finds the right fit. She describes her approach as closer to a forensic post mortem, an apt reference to the No.11 Swann-Morton scalpels she uses. “You get that kind of click when images suddenly connect,” she says. “It’s almost like fighting to breathe and then it’s like, OK.”

Art on the Underground will present a major public commission by Linder at Southwark station, launching on November 9 2018, and on view until October 2019. The Bower of Bliss, the first large-scale public commission by Linder in London, consists of a street-level billboard at Southwark station and a cover commission for the 29th edition of the pocket Tube map. In February 2019, Linder will have a solo show at Modern Art, London.

The A/W18 ‘Romance and Ritual’ issue of Another Man is out now. Buy a copy here.