Photographer and professor Andrew Moisey is launching a timely book about American fraternities – here, he reveals their relationship to the way male power is expressed in the US

- TextTed Stansfield

It’s clearer now than ever before that some men in positions of power behave appallingly, and even criminally. But, as Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation this weekend proves, their behaviour, whether past or present, rarely precludes them from being allowed to take on authoritative roles. Where was this behaviour learned? Photographer and professor Andrew Moisey argues that, in America, it’s in college fraternities.

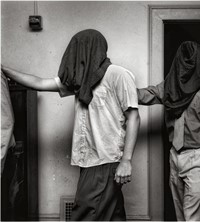

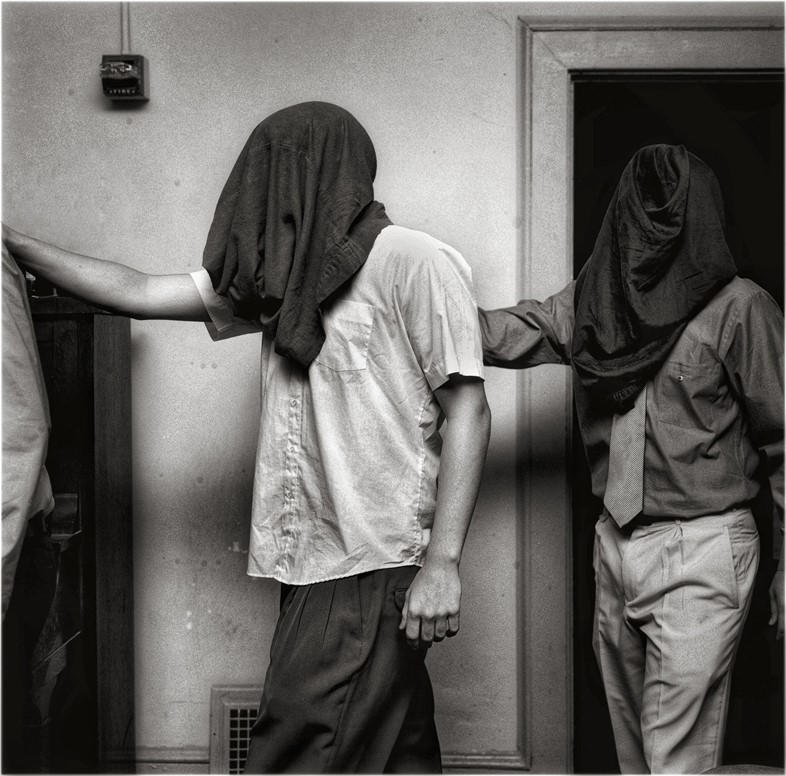

Moisey began photographing fraternities when his brother joined one, giving him unprecedented access into this secretive and often dark world. His images, which are published in The American Fraternity (out this month), shine a light on the rituals and initiation ceremonies of the organisations, as well as day-to-day life inside a fraternity.

As Moisey reveals, fraternities are more than just college societies: they are breeding grounds for toxic masculine behaviour. “As you turn the pages, you will marvel at the rituals, initiation ceremonies, historic texts, and the candid, often disturbing photographs. You will begin to understand why the college fraternity is not a passing phase, but the historical fountain of leadership for a hubristic, chauvinistic, male pleasure fortress – the modern United States.”

Kavanaugh himself was in a fraternity, along with 18 Presidents, 20 Vice-Presidents and countless others including members of Presidents’ cabinets, senators, representatives, and CEOs and founders of major corporations – all of which Moisey reveals in his book. Here, he explains more, revealing the truth about American fraternities and their relationship to the way male power is expressed in the US.

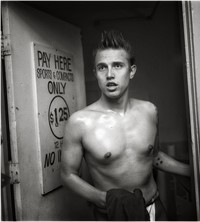

What was it like spending time in a fraternity?

Andrew Moisey: I mean usually you’re having totally innocent fun and sometimes you’re doing something dangerous, or something that would definitely be offensive to other people if they were around to see it, and you’re like ‘well, so long as these things stay behind closed doors I guess that’s okay’. But then you start to realise that the culture that you grow up in, behind closed doors, is the one that you take outside of it too.

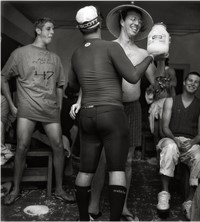

Do you think these guys had closer relationships that perhaps they would have done if they hadn’t been in the same fraternity?

AM: You know, that’s one of the biggest questions. I always wondered ‘are they closer with each other than I am with my friends?’ And I think that the answer is ultimately, no. And here’s why: I think that there are moments in the fraternity, and in their bonding rituals and in their activities, when they do feel closer to each other than most guy friends would feel to each other. But, I don’t think it lasts.

“We [the US] end up doing what we want to do anyway, on the world stage, as men in our society. And you see that incubated in a fraternity” – Andrew Moisey

A lot of those rituals seem quite religious. What is the relationship between these fraternities and organised religion?

AM: There’s a historical relationship and a conceptual relationship. The historical relationship is that there was a time in the United States when, if you weren’t a Christian, you weren’t really accepted as a real American citizen. And there’s also a very strong strain in the United States that started in Europe with the Freemasons. It’s sort of a romantic thing, where everybody is trying to get towards some higher spiritual feeling. The tools that they have to do that are the rituals and the processes that are already part of established religion.

But, I have to say that it’s just like with regular religion – you can’t just pledge allegiance to a set of principles and hope to live by them. It’s the story of the United States in general – that everyone pledges allegiance to the flag, and they say their prayers in church, and they don’t behave anything like Abraham Lincoln or Jesus Christ. And you can’t have – and the church deep down knows this – a capitalist system where it’s everybody for themselves and try and follow the teachings of Christ. It doesn’t make any sense.

So, that’s why I see the book as a microcosm of the rest of the United States, because we have these high ideals that were expressed in our declaration of independence, and, you know, our churches, but we don’t follow them. We end up doing what we want to do anyway, on the world stage, as men in our society. And you see that incubated in a fraternity. And you really see it for the first time in this book.

Do you think in America, where there’s a more recent history, there’s a greater desire to feel connected to something that’s older and more ancient?

AM: I think you’re definitely right. I think in the United States, the whole challenge of the entire United States is to try and create a community, like a giant community, from scratch. And so that’s one of the reasons why they choose to be Greek lettered societies, so they can harken back to a common culture that everyone shares in the West. And it goes all the way back, and I looked at a lot of fraternities, and a lot of them talk about the origins of fraternities being the Elysian mysteries back in ancient Greece.

Do you think that fraternities are becoming more inclusive and accepting?

AM: I won’t be able to tell you which fraternity this is, but if you go onto any fraternity at Berkeley’s website almost every single one of them will be touting how accepting they are. And I think that for the most part, they’re starting to follow through on this. But the thing is, that’s just window dressing. The question is about behaviour. The question is about lessons learnt. It doesn’t matter, at least in my view, what colour your members are – it’s about what lessons are learned.

“I feel it’s true that if we didn’t have fraternities, that Trump would never be president” – Andrew Moisey

I found one of the most striking parts of your book was near the beginning, where you had that list of US presidents who’ve been members of fraternities…

AM: I think it’s no surprise that the way that other countries see America, is the way that Americans see fraternity boys. I don’t think we’ve realise the extent to which our leaders behave with the same kind of hubris, chauvinism and American exceptionalism. I don’t think we realise just how many parallels there are in that with the way that fraternity men behave within the United States.

And it’s not just the presidents. It’s congressmen, it’s the bishops of the church, it’s the CEO. Once you’re in a fraternity, you’re also part of a network, and you learn how to behave around other men, so you can fall into their good grace, because this is the culture that you need to learn. And that’s one of the reasons why I think we need to talk. It’s kind of like a secret handshake, pulling you up the ladder.

Do you think there are any good things about fraternities?

AM: I think the good things are that, you just leave with lots of fun memories. And I think that if the wildness stayed within the walls of the house it could be almost beautiful. My book doesn’t capture what most fraternity men would say are the good things. But I’m not convinced that those good things outweigh the problems that they cause in the United States. I think that one of the reasons why we have Donald Trump is because people go to college accepting the kind of behaviour that he has, that he invites. Too many fraternities act like Donald Trump. Too many people grew up, and became adults, around people like him. Like, George W Bush. He was like the ultimate fraternity person. And I feel it’s true that if we didn’t have fraternities, that Trump would never be president.

The American Fraternity, published by Daylight Books, is out now