The Inside Story of HR Giger’s Idiosyncratic Museum in the Swiss Alps

- TextHannah Lack

Hidden inside a snowbound medieval castle lies the world’s largest collection of work by master of sci-fi nightmares, HR Giger. From biomechanoid orgies to alien space jockeys, we take a tour around the visionary artist’s legacy

Taken from the S/S18 issue of Another Man:

A miniature train winds its way up from Lake Geneva to reach Gruyeres, a walled medieval town of picturesque wooden chalets topped by a fairy tale castle. Most day-trippers visit this Alpine hilltop for the fondue, but others make the pilgrimage for a less wholesome attraction: in 1998, Hansruedi Giger – HR Giger as he’s better known – opened the rambling Chateau Saint-Germain here as a permanent home for his pitch-black work. It’s an incongruously idyllic setting for the Swiss artist famous for translating his night terrors into surreal visions of biomechanical horror; the day we arrive, a blizzard has transformed the landscape into Narnia, and the Giger sculptures guarding the museum’s entrance – a pack of goggled baby foetuses stacked inside a gun chamber and a rusted female torso with lethally spiked nipples – are encased in shrouds of snow. Opposite them sits the Giger Bar, its interior resembling a crash-landed spaceship with a ceiling arched by knobbly vertebrae. (Unlike the unofficial version of the bar that opened in Tokyo in the 80s, this one isn’t a favourite of the Yakuza.) Inside, patrons lounge on spinal-chord swivel chairs and sip Face Huggers (red vodka, Baileys) in homage to Giger’s chest-bursting Xenomorph, the grisly creature that slithered out of his imagination and onto the big screen in Ridley Scott’s defining 1979 sci-fi Alien.

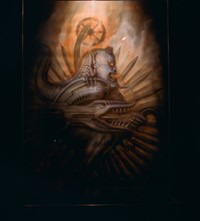

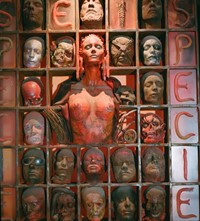

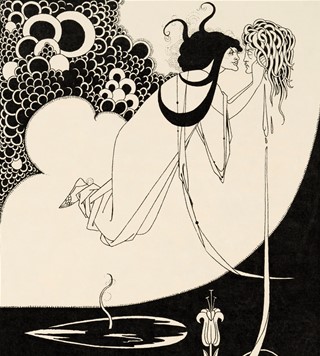

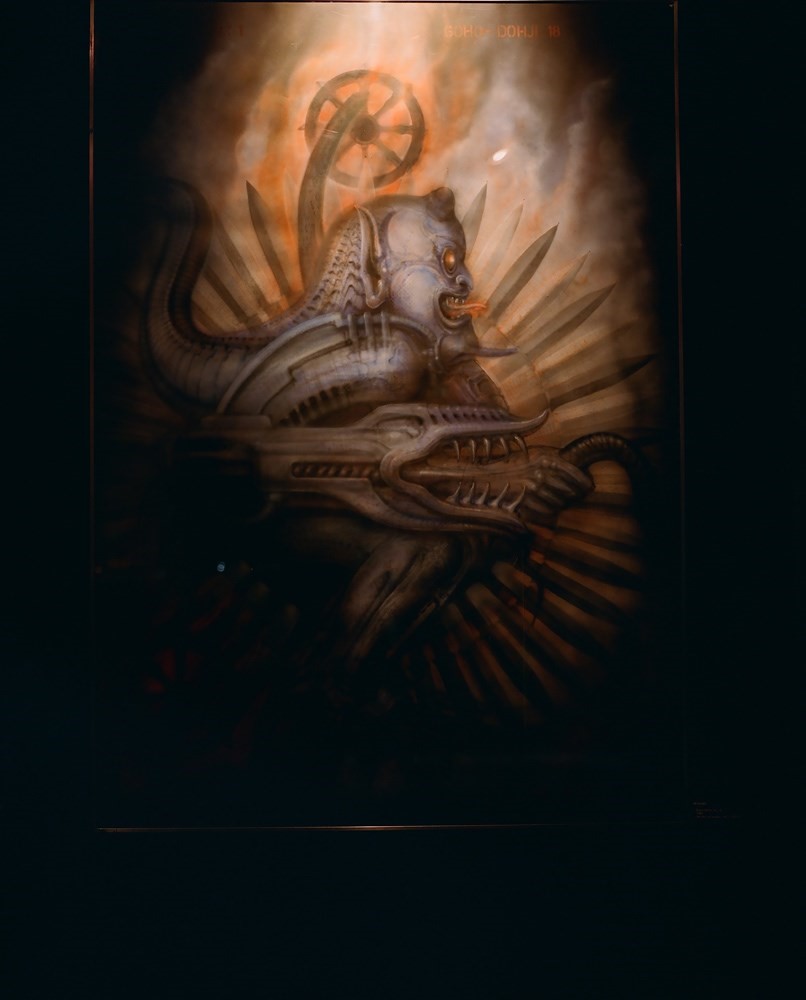

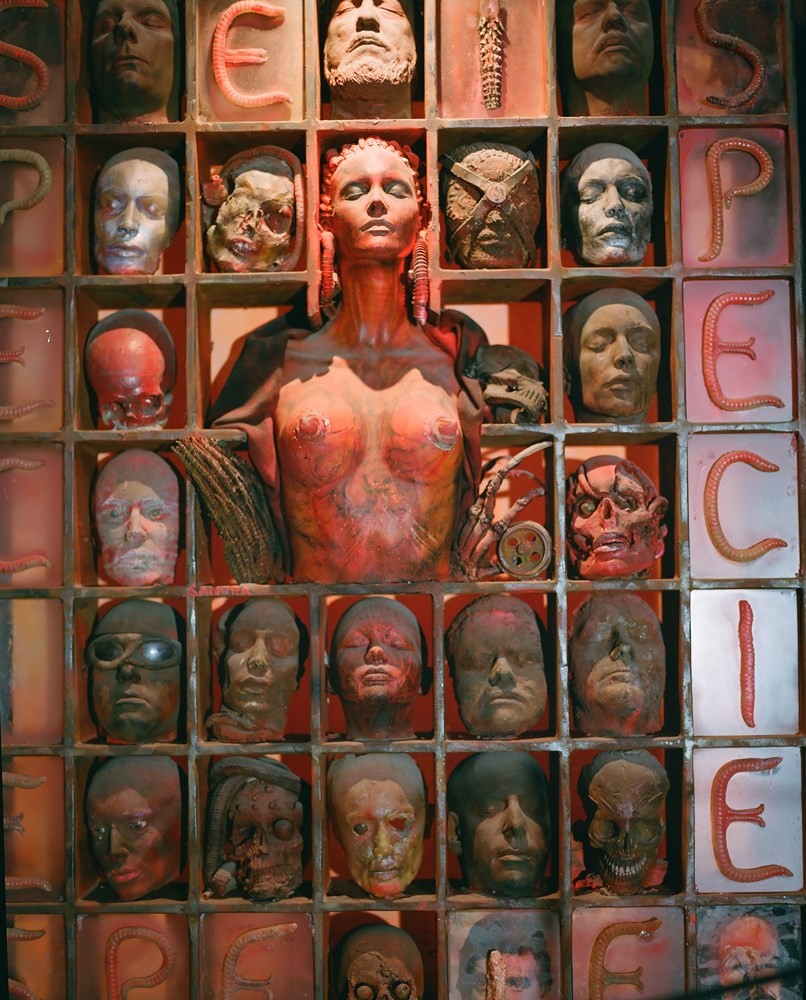

Since Giger’s death in 2007, his widow Carmen Giger Scheifele has continued to oversee his idiosyncratic museum, which celebrates its 20th anniversary this year. “He viewed it as his Lebenswerk, his legacy,” she tells us from her home in Zurich. “Hansruedi had long nurtured the idea of a permanent home for his art, not unlike the museums established by his friends Ernst Fuchs or Salvador Dalí. It was a project that would never really be finished; he still had many ideas he wanted to implement.” One sadly unrealised plan involved installing a ghost-train that would allow visitors to strap themselves in for a ghoulish ride through decades of his artwork, with the odd pop-up surprise. For now, we make do with walking through the shadowy, lair-like museum on floors constructed from a matrix of cast-aluminium circuit boards, as though we’re on board the Nostromo. Despite ominous rumbles from avalanches in the mountains above the town, the chateau’s stone walls feel robust enough to protect against even the nuclear-style apocalypse hinted at in the paintings on display: There are yawning underground shafts with Escher-like staircases descending into the abyss, and rare coloured oils inspired by the writings of Samuel Beckett. A handful of rooms are devoted to Giger’s vast airbrushed works of biomechanoid orgies and nubile goddesses harnessed to torturous-looking implements, psychosexual scenes that suggest both a fascination for and a deep fear of the female body. One hall is filled with sketches and sculptures for Alien – an alarming prototype leers down between multiple rows of teeth from the ceiling – as well as collections of Tarot cards, elaborate gothic furniture, and even some sado-masochistic designs for Swatch, which the Swiss firm never had the courage to take Giger up on. In an alcove hidden by a thick velvet curtain, a glowing red room displays his most X-rated forays, including 1973’s Penis Landscape, the painting that landed the Dead Kennedys on trial for obscenity when they included a poster of it in their LP Frankenchrist. (Giger designed numerous album covers, memorably impaling Debbie Harry’s face with enormous nails on her 1981 solo debut Koo Koo.)

“He viewed it as his Lebenswerk, his legacy. Hansruedi had long nurtured the idea of a permanent home for his art, not unlike the museums established by his friends Ernst Fuchs or Salvador Dalí. It was a project that would never really be finished; he still had many ideas he wanted to implement” – Carmen Giger Scheifele

The collective experience is a woozy ride through the depths of the human subconscious, spanning merciless visions of overpopulation, mechanisation and automation, nuclear holocaust and the tortures of birth, clashing otherworldly horror with moments of beauty. If, as the title of his 1966 portfolio of limbless bodies on rickety wheels acknowledges, his spectres are a “Feast for the Psychiatrist”, Giger’s work is also among some of the most prescient of the 20th century in its disturbing fusing of man and machine. “Of course it was a way of confronting his fears,” says Carmen of the artist’s dredging up and externalising of his anxieties on canvas. “But it was also a process he could not fully control; Hansruedi sometimes couldn’t help wondering if he was some kind of relay for forces or images that existed on another, non-material level.”

On the surface, the bourgeois Swiss town of Chur beside the banks of the Rhine, where Giger was born in 1940, seemed to offer little fuel for his feverish imagination – but the atrocities of WWII ensured death was a preoccupation from an early age. His father owned a pharmacy, where the young Hansruedi obtained a human skull that he would drag around the streets on a string. “As soon as I could dress myself I wore black,” he once told the Swiss Public Broadcasting Corporation. An avid reader of Poe and HP Lovecraft, his favourite Sunday outing involved visiting an Egyptian mummy princess in Chur’s local museum: “This mysterious black body attracted me tremendously, but it also scared me. Primordial life processes have always fascinated me.”

“Of course it was a way of confronting his fears. But it was also a process he could not fully control; Hansruedi sometimes couldn’t help wondering if he was some kind of relay for forces or images that existed on another, non-material level” – Carmen Giger Scheifele

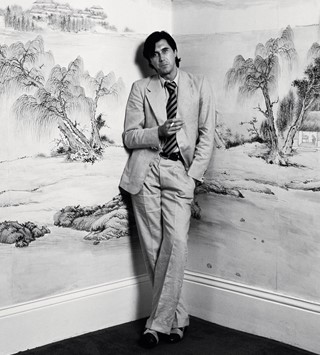

He was at Zurich’s School of Applied Arts studying industrial design in the early 60s when he began publishing his first artworks in underground magazines – inky drawings scratched away with razor blades depicting boney figures with stretched skulls and respirators: cyberpunk well before its time, mining themes of sex and death that would pervade his life’s work. In 1966 he met pivotal muse Li Tobler, a beautiful and troubled 18-year-old actress whose features he would go on to capture myriad times over their nine-year relationship, emerging from nests of snake-like cables and skulls in many of his most famous works. The pair shared a draughty, condemned industrial building in Zurich, where Giger painted through the night, eventually giving up a job as furniture designer to devote himself fulltime to his art. Early exhibitions weren’t always popular in his native country – galleries reported having to wipe spit off the windows from outraged local residents. But for Giger, the impulse to create was unstoppable: “Since choosing to pursue art, it has been like an LSD trip – with no return,” he said. “I feel like a tightrope walker and no longer differentiate between work and leisure. I suddenly realise that ‘making art’ is a vital activity for me to keep from going insane.”

Tobler meanwhile suffered her own battles with mental health. In and out of clinics and struggling with depression, in 1975 she committed suicide in the house the couple then shared in the north of the city, shooting herself with Giger’s own 5mm revolver. He remained living in the ivy-covered cottage for the rest of his life, building a chaotic retreat filled with an ephemera of artworks, books, hoarded newspapers, and a beloved and intractable Siamese named Muggi. Walls were painted black and shutters permanently locked to daylight, with the exception of a glass door leading into a small garden dotted with fruit trees. (When third wife Carmen married him in 2006, she moved next-door; an Egyptian sarcophagus connected the entrance between the two buildings.)

“Darkness isn’t solely something negative, something sad, something dreadful. Hansruedi never saw it in such a one-dimensional manner. Not only is darkness an integral part of every human life and the entire universe around us, it’s also capable of conveying something deeply majestic, tranquil, and alluringly attractive” – Carmen Giger Scheifele

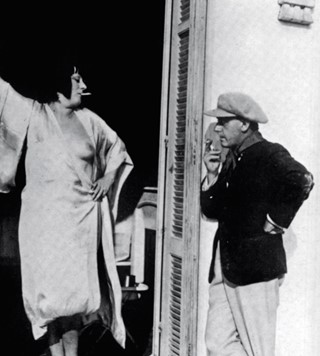

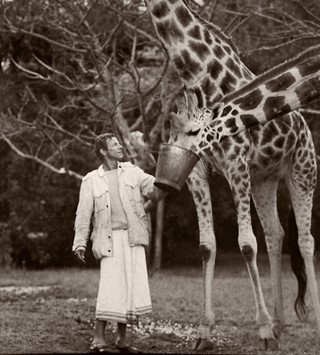

The same year Tobler died, Giger was introduced to one of his most profound artistic influences, Salvador Dalí; the pair hung out together at the flamboyant, bejewelled artist’s house in Cadaqués. Their encounter would kickstart Giger’s groundbreaking work in cinema: it was Dalí who introduced him to cult Chilean auteur Alejandro Jodorowsky – they met at a French prog-rock concert – who then commissioned Giger to design the gothic planet Harkonnen for his sprawling, ill-fated sci-fi Dune. Tantalising sketches of Giger’s imaginary world include a squat, egg-shaped castle built on jagged bones and excrement, with an unfurling drawbridge guarded by shark’s teeth. The colossally ambitious film eventually burned up in a deranged haze of marijuana smoke and budget-blowing celebrity casting, but it lead two years later to the movie that brought Giger global fame: In 1978 he was invited by Ridley Scott to create the monster and sets for his fledgling project Alien. Settling in a room above a pub near Pinewood Studios in Shepperton, Giger spent 11 months constructing prototypes made from Rolls-Royce parts, animal bones, neon-green toy-shop slime and shredded condoms to realise his nightmarish extra-terrestrial brainchild with its elongated skull, spiney exo-skeleton and slick phallic protuberances. The terrifying results won Giger an Oscar in 1980 for best visual effects – his gold statuette lives in a glass case inside the museum today – and forever shaped science fiction movies to come with a wildly original aesthetic that has been endlessly imitated.

But the film projects that followed – Poltergeist II, Species, the deeply inauspicious Killer Condom – never gave Giger the freedom he enjoyed on Scott’s set. Meanwhile, the huge commercial success of Alien temporarily confused the stuffier corners of the art world about his serious artistic credentials, a reaction that has rightly been reappraised in recent years. Giger’s work has left an indelible mark on popular culture – on film, music and on the tattooed limbs and torsos of some of his most loyal fans, whom he considered walking open-air exhibits. In the 2014 documentary Dark Star, scenes shot at a book signing show muscled, tearful men stripping off to display full-body tattoos of his work inked into their skin, addressing Giger as “master” and bowing as they shuffle backwards. You can spot the odd devotee prowling around Gruyeres today, dressed head-to-toe-cap in black, amid the town’s twinkly fairy lights and vats of hot chocolate. They, like Giger, have always seen the light as well as the dark in his work. “Darkness isn’t solely something negative, something sad, something dreadful,” says Carmen. “Hansruedi and I never saw it in such a one-dimensional manner. Not only is darkness an integral part of every human life and the entire universe around us, it’s also capable of conveying something deeply majestic, tranquil, and alluringly attractive.”

“Giger’s work spooks us because of its enormous evolutionary time span. It shows us, all too clearly, where we come from and where we are going” – Timothy Leary

Perhaps Giger managed to flee his vivid fears by choosing to make himself at home among them; in the last years of his life, death no longer seemed to haunt him as it did in his earlier days. If his work continues to disturb us, it’s because, as the artist always insisted, he painted from reality. “Giger’s work spooks us because of its enormous evolutionary time span,” said psychedelic guru Timothy Leary. “It shows us, all too clearly, where we come from and where we are going.” He will probably always remain most famous for the Alien phenomenon – merchandise over the years has even included Alien backscratchers. But spend time at his extraordinary museum and it’s clear that Giger, like many legends associated with science fiction, was less concerned with the far reaches of the stratosphere than with humankind here on earth: his hive-like insect cities, larval creatures, astro-eunuchs and atomic children were us all along.