‘People didn’t really know men pictorially’: as a new exhibition of her work opens at Modern Art in London, the Another Man contributor talks capturing men and collaging women

- TextMaisie Skidmore

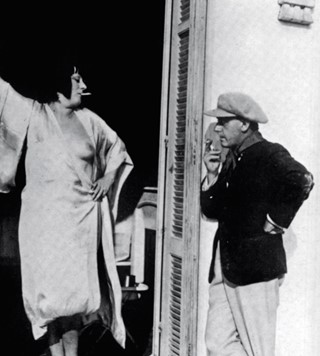

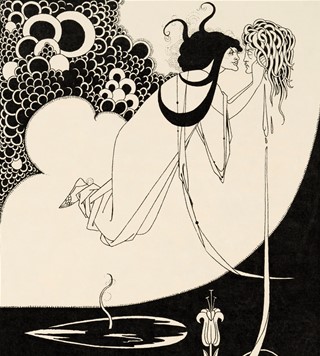

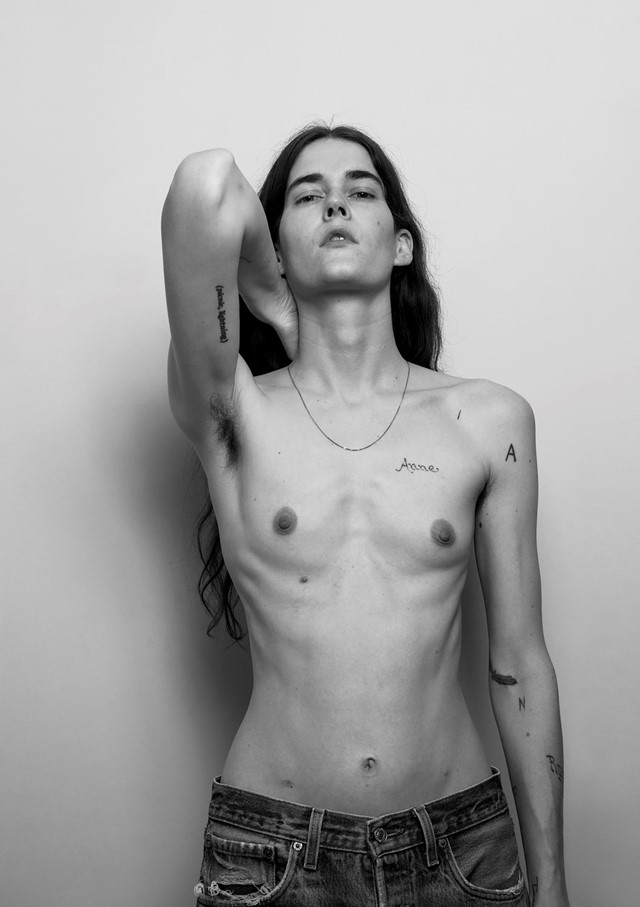

“I tasked myself with remaking pictures that I didn’t like,” Collier Schorr tells Another Man, as she finishes installing In Front of the Camera, a new solo exhibition at London’s Modern Art gallery which effortlessly straddles her work for fashion magazines, and as an artist in the studio. She’s talking about Jens F, a book which was first published in 2005. Though conceptually complex, it was built on a simple premise: recreating Andrew Wyeth’s The Helga Pictures, with an androgynous male model substituted for Wyeth’s curvaceous original sitter.“I didn’t like them because half of the time the woman was naked, and in such antiquated poses… A boy and I were trying to recreate these pictures, he was struggling to hold these female poses, and I was struggling to be connected to these historical poses.”

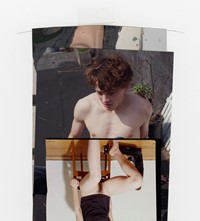

Together they persevered, Schorr pasting contact sheets of the resulting images she had made and liked over Wyeth’s original paintings and sketches, until the existing book metamorphosed into a kind of sketchbook, documenting a point of tension in representations of the body from the past and the present. Subsequently published by MACK, then an imprint of Steidl, Jens F. has since become an icon of art books. “When it was published absolutely nobody bought the bloody thing,” publisher Michael Mack told AnOther earlier this year, “and now it’s acclaimed as being one of the great books of all time.”

Not only did Jens F. usher in a new era in which to examine our preconceptions about the body, and the different ways we document it, it also prompted Schorr to push the boundaries of her medium. “But by the end of [making] it I really had much more of a sense of fine art drawing – history, anatomy, shadows on bodies and muscles – which I hadn’t known before,” she continues.

“It was an exciting time to use all the ways that we were looking with desire at women, and to turn that on to boys” – Collier Schorr

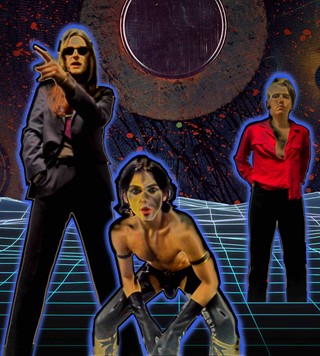

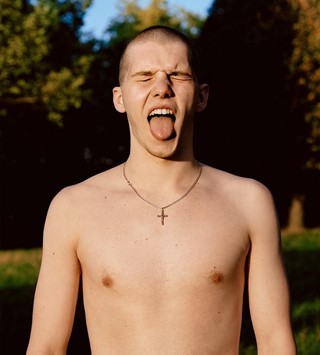

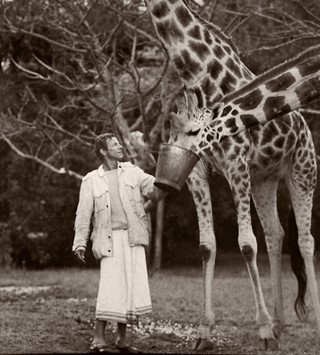

For ten years Schorr focused her lens on boys, motivated by the overabundance of images of women that she encountered in the world. “In the early days that’s why I took pictures of boys in Germany, pictures of wrestlers in America, pictures of boys in fashion,” she explains. “I wasn’t sure if I had a new picture of women to make, because there were so many existing already. And there was a point when people didn’t really know men pictorially – so it was an exciting time to use all the ways that we were looking with desire at women, and to turn that on to boys.”

The works she made during this period are intimate, sensitive, emotionally charged. But there was a masochistic underbelly to them too, she says. “Honestly, part of it was punishment. I did come to it with this sense that I was going to strip men a little bit, make men vulnerable, as a response to all the pictures of women that had been vulnerable.”

“Honestly, part of it was punishment. I did come to it with this sense that I was going to strip men a little bit, make men vulnerable, as a response to all the pictures of women that had been vulnerable” – Collier Schorr

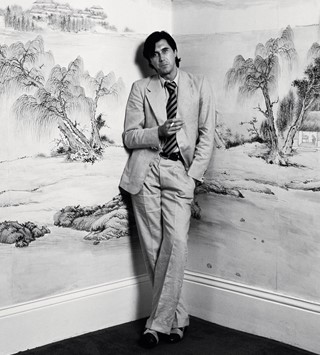

As Schorr’s work in fashion – for publications such as Another Man (she has shot Vincent Gallo, Sergei Polunin and David Beckham for the magazine) and Dazed to brands including Comme des Garçons and Saint Laurent – pushed her to photograph the female figure again, she began incorporating collage into her practice in a more explicit way, slicing up and fragmenting the body in order encourage her images forwards.

Which idea cuts to the very heart of Schorr’s work, which is always underpinned by an emotional connection to her subjects. “There are so many platforms for pictures now – so many magazines, so many people wanting to make pictures, so much ease in it now compared to what it was like years ago,” she says. “There are definitely people working today that pose the body in really extreme ways in order to make new content. What I want to see is still the artistic impulse that’s making a reason for that picture to exist, rather than propelling a model into extreme discomfort.”

She’s still pursuing a new image, she says – a fact the exhibition testifies to, with its tender and many-layered reconfigurations of the relationship between artist and sitter. But now she has new tools at her disposal through which to grapple with it. “I wouldn’t take credit for making a picture that people haven’t seen, but I would take that credit for making a collage that people haven’t seen,” she concludes. “That’s easier for me: I would rather cut a body in paper than open up a body and turn it upside down in real life, for sure. That’s the way for me to disturb the pictorial space.”

In Front of the Camera runs until September 1, 2018, at Modern Art, London