The Artist Changing Conversations About Masculinity in South Africa

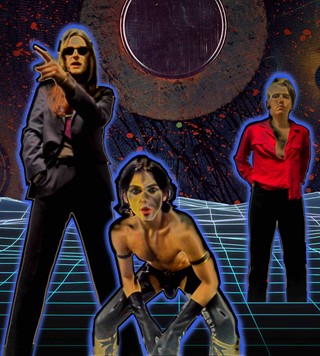

Actor, musician and novelist Nakhane has been at the centre of a heated controversy following his role in ‘The Wound’, a tale of closeted sexuality in rural South Africa. Here, Another Man meets this fearless star

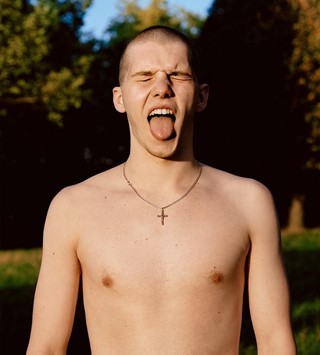

A few weeks ago, the Oscar-shortlisted The Wound – an unsettling film exploring sacred rites of passage and notions of masculinity within South Africa’s Xhosa community – nearly swept the board at the South African Film and Television Awards (SAFTAS). Inspired by a novel by Thando Mgqolozana, the Sundance-screened feature took home six of the eight prizes it was in the running for, including Best Film, Director, Screenplay, Supporting Actor (Bongile Mantsai), and Actor (Nakhane). For a film that’s been mired in controversy and a highly mediatised court battle (South Africa’s Film and Publications Board initially slapped it with an X18 rating, usually reserved for hardcore pornography), the awards sweep served a decisive blow to those who’d been trying to keep a lid on the complex issues it lays bare.

For its lead actor, Nakhane Touré, who recently relocated from Johannesburg to Dalston in East London after being on the receiving end of the most virulent ire (and death threats) from The Wound’s detractors, that SAFTA victory was huge. Not only was his brave and deeply resonant portrayal of Xolani, a taciturn gay factory worker who oversees teenagers as they undergo the initiation ritual his first professional acting role, but the film also touches upon the highly fraught experience the 30-year-old musician and novelist also had when he was ushered into manhood. Whatever that word means.

“Maybe I sound a little too 21st century neo-gender theory,” jokes Nakhane when I reach him by phone in late February, shortly after his move to the UK. “I think the basic idea of ‘manhood’ is problematic in itself. It’s a construct. But for those who choose to live by that construct, ulwaluko can be really beautiful,” he says of Xhosa culture’s cornerstone ceremony, which brings together boys in their late teens (‘initiates’) to be ritually circumcised in secluded camps while mentored by men from their communities. “It can be really great for a community of boys who can love each other and finally show vulnerability,” he offers.

The heavy burden of responsibility

Nakhane, a singer-songwriter who grew up in a conservative, religious household in South Africa’s Eastern Cape province, had initially wanted to recount his own Xhosa initiation in a book. That is, until he read the script for The Wound and decided co-writers Malusi Bengu and John Trengove (also the director) had pretty much nailed it. “At that point, I was still very interested in being part of the film in some capacity, because I really enjoyed the script and thought it was an important film to be made.” After meeting with Trengove to contribute music to the film, the director took Nakhane by surprise when he offered him The Wound’s lead role – something he readily accepted, while knowing it came with a heavy burden of responsibility to the Xhosa community – South Africa’s second-largest population group, estimated at roughly 9 million people.

“So while ulwaluko is a time to show love, weakness and pain amongst boys, it’s also a breeding ground for misogyny, homophobia and a kind of toxic masculinity that goes unchecked,” Nakhane points out, arguing that those within the community who criticise it are ostracised, as this film has proven. “No one wants to own up to the fact that culture and traditions must change over time, including this one.”

“While ulwaluko is a time to show love, weakness and pain amongst boys, it’s also a breeding ground for misogyny, homophobia and a kind of toxic masculinity that goes unchecked” – Nakhane

In recent months, Nakhane has found himself in an incredibly precarious position: wanting to defend the Xhosa community from outsiders who simply write off the beauty and value of centuries-old rituals on the basis of its most problematic elements, while also wishing to call out the erasure of queer bodies in these Xhosa initiation rites. Suffice it to say there’s no sound bite that can neatly package his conflicted feelings on the matter. “That’s what hurts the most,” he concludes. “I love these men. I grew up around them. They made me laugh, they taught me things. They also hurt me and continue to do so, but I still don’t want people from outside my community to fuck with them, because they’re my father, my uncle, my brother, my cousins.”

That said, he recalls getting extremely emotional following the announcement of the film’s X18 rating (which was overturned after our interview), and which in many ways acted as an outright ban on the themes and characters brought to light in The Wound. “It just reminded me of my childhood – of the precariousness of walking from my house to the shop, seeing straight men in the street and not knowing what they would do to me,” he describes, adding that he thinks twice before saying, writing or tweeting his thoughts on what is by all accounts a very delicate topic. He remembers feeling hurt upon digesting that verdict, along with criticism of the film as a “misrepresentation of the culture”. “I didn’t even want to see that repressive move as being solely about the film. I thought of my queer friends and family members. I mean, how dangerous is that decision? It’s all just veiled homophobia.”

Tom Waits and the sounds of gay techno clubs

Growing up, Nakhane instantly took a liking to music, which helped him understand the world and his feelings. Listening to Marvin Gaye’s falsetto, for instance, allowed him to accept his high-pitched voice as nothing to be ashamed of. Music provided him with an outlet to channel all those hard-to-unpack emotions and struggles. He describes his new album You Will Not Die, released last month, as a mix of acoustic guitar and the sounds of gay techno clubs. “As a black queer man, that’s my punk music. If you look at the history, these kids on the fringes of society with no money and shit equipment made something out of it. And others didn’t have to like it. That’s what I like about the techno and house music of the 1970s and 1980s, and the Paris is Burning scene.”

“As a black queer man, [techno is] my punk music. If you look at the history, these kids on the fringes of society with no money and shit equipment made something out of it” – Nakhane

This Rufus Wainwright and Leonard Cohen fan recalls discovering that the universe had gifted him with something “that loved me without demanding anything back.” “When I went through the [Xhosa] initiation, my uncle smuggled a Bible and an MP3 player into my hut, because he’s very musical and has always been there for me. In the player, there was Nick Cave, Tom Waits, PJ Harvey’s Uh Huh Her, The White Stripes’ Elephant and a bunch of West African music. All that stuff really changed my life. Because if you listen to Tom Waits’ Time, those lyrics are just unbelievable. That’s poetry. I appreciated how these artists could make me think and feel with a turn of phrase.”

Myopic colonisers and ‘the African dialect’

Hearing about Nakhane’s first-hand experience with ulwaluko reaffirmed director John Trengove’s desire to cast Xhosa men who’d gone through the initiation ritual themselves for The Wound. In interviews, Trengove has talked about how the film was born out of a desire to push back against stereotypical portrayals of black masculinity on screen, and to unpack the notion that homosexuality would somehow be ‘un-African’, as former Zimbabwe president Robert Mugabe has often suggested. Nakhane and I both agree those clichés and misconceptions aren’t the exclusive domain of cinema, but rather part of the many unresolved aftershocks of colonisation. Why do certain African leaders make these “homosexuality = Western decadence” pronouncements in the first place, for instance? Why aren’t we talking about the conservative religious traditions that colonisers forced upon the continent in the first place?

“To be honest with you, it’s really frustrating sometimes when I do press in Europe, especially when the question is – actually, it’s usually a statement, that Africa is much more homophobic than Europe. And that’s not necessarily true. Europe is so proud of itself for being ‘progressive’, while South Africa was one of the first countries in the world to legalise same-sex marriage. Do you know what I mean?”

“Europe is so proud of itself for being ‘progressive’, while South Africa was one of the first countries in the world to legalise same-sex marriage” – Nakhane

The arrogance and irresponsibility that come with applying a Western frame of reference to social mores and practices in non-Western parts of the world is something we agree needs to be called out. Nakhane then turns to Lars Von Trier’s Nymphomaniac to build on that idea. “I’ll always remember the scene where Charlotte Gainsbourg’s character goes up to a translator and says, ‘I understand that you speak the African dialect.’ I remember turning to my boyfriend and saying, ‘What, all of them?’ There are 11 official languages in South Africa alone, and each one has like 10 dialects. Let’s not even talk about Nigeria, where there are like 40 languages and each one has many, many dialects. This ignorance of ‘the entire Africa’, and how ‘the entire Africa’ needs the same kind of emancipation as Europe is so problematic and dangerous. Yes, of course we all want the same things. There just needs to be some sensitivity to what certain people have done to others. The scars remain. And actually, they haven’t even scarred yet. Where I come from, they’re still festering wounds, man.”

The Wound hits UK theatres 27 April

Nakhane’s new album You Will Not Die is out now