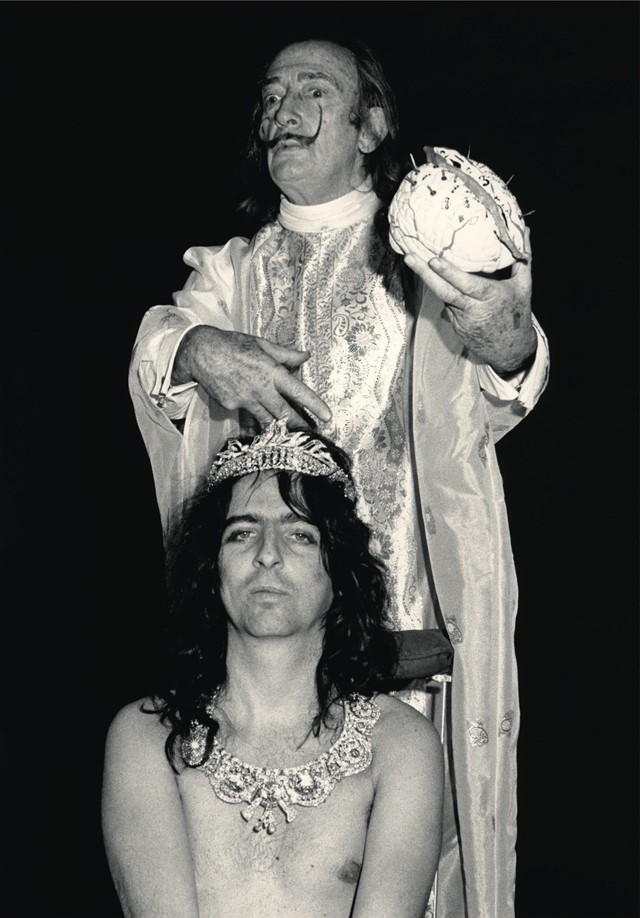

Alice Cooper Remembers His Encounter with Salvador Dalí

- TextPaul Moody

In 1973 Salvador Dalí created a portrait of Alice Cooper’s brain using chocolate éclairs, ants, diamonds and early holographic technology. Here, the notorious shock-rocker remembers his eccentric encounter with art’s surrealist king

Taken from the S/S18 issue of Another Man:

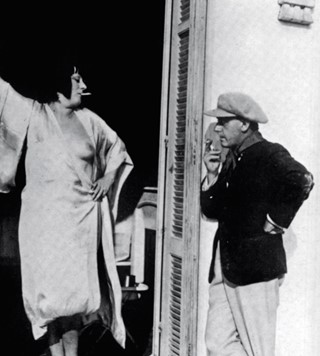

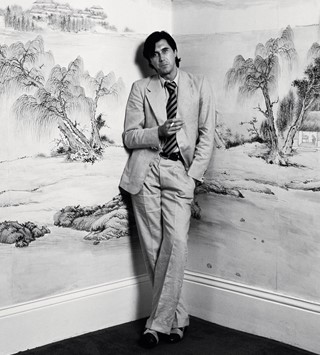

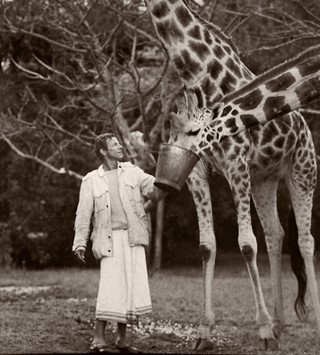

April 1973. Even by the louche standards of the St Regis Hotel – a deluxe 1904 Beaux-Arts bolthole in midtown Manhattan frequented by Marlene Dietrich, Ernest Hemingway and John Lennon – it was quite an entrance. “All of a sudden these five androgynous nymphs in pink chiffon floated in,” says Alice Cooper, recalling his first encounter with Salvador Dalí in the hotel’s King Cole Bar. “They were followed by Gala (Dalí’s wife) who was dressed in a man’s tuxedo, top hat and tails, and carrying a silver cane. Then came Dalí. He was wearing a giraffe-skin vest, gold Aladdin shoes, a blue velvet jacket and sparkly purple socks given to him by Elvis.” Having announced his presence with a syllable-stretching cry of “The Da-lí… is… he-re!”, the artist requested a round of ‘Scorpion’ cocktails for his guests: rum, gin and brandy served in a conch shell, topped with an orchid. He then ordered himself a glass of hot water. Taking a jar of honey from his pocket and setting the glass on a pedestal, Dalí began pouring the liquid into the glass, dramatically raising it higher so that it formed globules on the surface. Cutting the stream with a pair of scissors, he then raised his arms in a dramatic flourish, prompting a round of applause from his acolytes. “Me and my manager looked at each other in amazement,” says Cooper. “I realised at that point that everything was about Dalí. The world revolved around him. I wasn’t meeting him. I was entering his orbit.”

So began one of the strangest and most fascinating artistic encounters of the 20th century. In 1973 both Cooper and Dalí – aged 25 and 69 respectively – were at the height of their powers. Now seen as the genial grandfather of shock-rock, at the time Cooper was the world’s most disreputable pop star. A string of seditious-sounding hit singles – most notably School’s Out – had tapped into a groundswell of teen disaffection that would later mutate into punk. His blood-spattered live show, meanwhile – featuring live snakes, beheaded baby dolls and fake blood, culminating in his nightly decapitation by guillotine – had made him the scourge of the establishment.

“All of a sudden these five androgynous nymphs in pink chiffon floated in. They were followed by Gala who was dressed in a man’s tuxedo, top hat and tails, and carrying a silver cane. Then came Dalí. He was wearing a giraffe-skin vest, gold Aladdin shoes, a blue velvet jacket and sparkly purple socks given to him by Elvis” – Alice Cooper

“His incitement to infanticide and his commercial exploitation of masochism is evidently an attempt to teach our children to find their destiny in hate, not in love,” MP Leo Abse told Parliament the same year, arguing that Cooper should be banned from the UK for promoting “the culture of the concentration camp”.

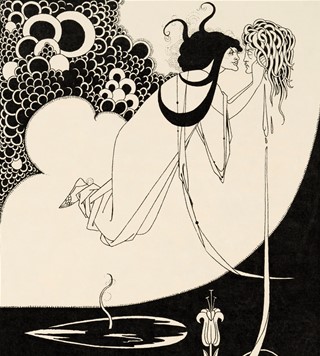

Dalí, of course, had long been seen as the master of the macabre. The superstar of surrealism, the Spanish artist was a born antagonist who lived by the mantra: “What is important is to spread confusion, not eliminate it.” Seeing Cooper’s success as an opportunity to create fresh outrage, he had hatched a plan to establish the duo as the planet’s presiding kings of weird. But there was one slight problem. When Dalí started to explain his idea of turning Cooper into the world’s first living hologram, to be called First Cylindric Chromo-Hologram Portrait of Alice Cooper’s Brain, his words came out not in English, but in a stream of nonsensical pan-European gobbledygook. “It would be one word in English, one word in French, one word in Italian, one word in Spanish and one in Portuguese,” says Cooper of Dalí’s surrealist Esperanto. “It made no sense whatsoever. You could only understand one-fifth of what he was saying.”

Despite the barrier to communication, Cooper’s heart leapt. As a teenage art major at Cortez High School in Phoenix, Arizona, Dalí’s fantastical paintings – littered with melting clocks, eggs and ants – had spoken to him on an equally unfathomable level. “Dalí was our hero,” he says, recalling the obsession he shared with schoolmate and future Alice Cooper band bass player Dennis Dunaway. “Before The Beatles came along, he was the only thing we had. We would look at his paintings and talk about them for hours. His paintings had a lot of humour in them too. So when we formed our own band it was only natural that we took some of those images – like the crutch – and used them in our performances.”

By the time of 1972’s million-selling School’s Out album, Cooper had become a global star. Holed up in a rambling 42-room mansion in Connecticut boasting a life-size Alice dummy hanging from the ballroom ceiling, a chapel converted into a sauna-cum-bar and a large menagerie including a boa constrictor called Yvonne, his day-to-day reality was as strange as anything in Dalí’s imagination. With such a high profile, it seemed inevitable that his hero should come calling.

“Dalí’s people rang my manager and explained that he’d seen one of my stadium shows,” explains Cooper. “He said it was like seeing one of his paintings come to life, and that he wanted us to work together.”

“With Dalí, everything was a performance. Each night we would go to Studio 54 or to see Andy Warhol at the Factory. Dalí always travelled with lots of bizarre characters, so I was happy just to sit back and take it all in. I wasn’t going to try and talk to him about art, because he was always using this funny language. I was in the presence of the master” – Alice Cooper

Needless to say, for all the theatrics at their first meeting, Dalí knew exactly what he had in mind for their joint venture. Two years earlier he had befriended a South African artist called Selwyn Lissack who was also staying at the St Regis (Dalí spent every winter at the hotel, always staying in room 1610). Lissack – then based in California – explained that while holographic techniques were still in their infancy, they would give him the ability to create art beyond the confines of linear space, using laser light as his paintbrush. Dalí – whose work had long reflected an interest in three-dimensional symmetry – was fascinated. Impressed by the examples Lissack showed him, created by associate Lloyd Cross, he offered the South African $500 to create a 12-inch by 24-inch hologram of Cooper known as a ‘multiplex’ which, when viewed from different angles, would appear to display an animated scene. To achieve such a task – completion of which would take six months – Lissack arranged for a vast array of highly technical equipment, including bulky tungsten halogen lights, mercury arc lamps and a 2mW laser, to be positioned in a large white-walled production studio at the St Regis for the start of the four-day shoot.

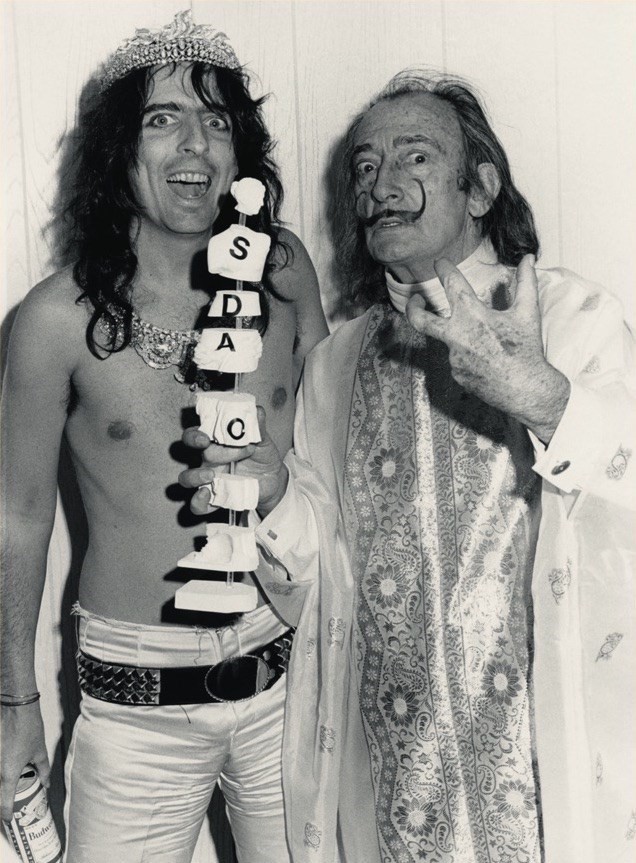

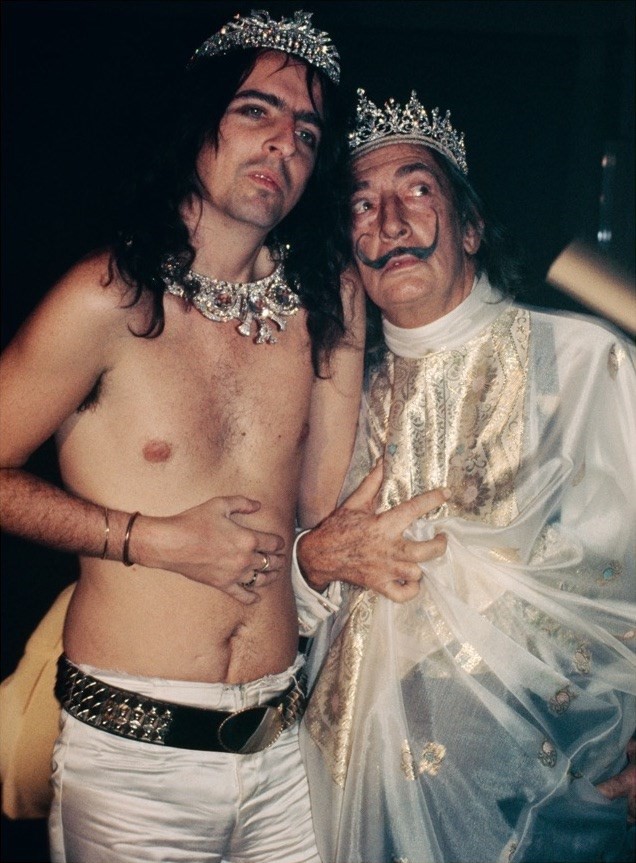

However, Dalí, ever the showman, ensured that proceedings would still come with a surrealist glaze. On the first day, in front of the assembled press corps, a man in a bowler hat arrived on the set carrying a black attaché case. Inside were a diamond tiara and necklace supplied by world-famous jeweller Harry Winston, valued at $2m ($30m today). These were then presented to Cooper and Dalí on a red velvet pillow by a beautiful woman, as a thuggish-looking guard brandishing a machine gun looked on. Dalí then instructed Cooper to take his shirt off, put on the diamonds and sit cross-legged on a rotating dais. As Lissack began filming in the round, Cooper was asked to alternately sing into, and take bites out of, a Venus de Milo-shaped statuette resembling a shish kebab.

“I wasn’t exactly sure what was going on,” admits Cooper with a chuckle. “Dalí was a character who was so mythical, you didn’t really want to say anything. For me, it was like meeting Elvis or The Beatles. It was obvious that he’d looked at me and seen what he wanted. All I did was say: ‘Tell me what you want me to do.’”

The second day brought more surprises. On arrival, Dalí announced that he had spent the previous evening working on a brand new artwork: The Alice Brain. He then presented the singer with a ceramic sculpture of a human brain with a chocolate éclair running down the back, painted with ants spelling out the words ‘Dalí’ and ‘Alice’. “I said: ‘That’s great, when we’re done can I have it?’” recalls Cooper. “He said ‘Of course not, it’s worth millions!’ I just laughed. He had a great sense of humour but his genius was that you never knew when he was being funny and when he wasn’t.” When the day’s shooting was over, Dalí asked Cooper and manager Shep Gordon to join him and his 20-strong entourage at one of the city’s most exclusive restaurants. As the lavish meal came to an end, Dalí waved away the waiter presenting the bill. Instead, he simply signed the tablecloth. “Shall I leave a tip?” responded Cooper, signing his own name below it.

“With Dalí, everything was a performance,” explains the singer. “Each night we would go to Studio 54 or to see Andy Warhol at the Factory. Dalí always travelled with lots of bizarre characters, so I was happy just to sit back and take it all in. I wasn’t going to try and talk to him about art, because he was always using this funny language. I was in the presence of the master.”

“He was the most bizarre character I’ve ever met. And yet after a while you felt very close to him. Working with him was one of the greatest moments of my life” – Alice Cooper

There would be one final twist. At the unveiling of the finished hologram at the Knoedler Gallery in New York later in the year, Cooper explained to the assembled press that communication between the pair had been limited given the language difficulties. “Perfect!” responded Dalí in perfect English. “Confusion is the best form of communication.” The master had been up to his old tricks again.

Today, First Cylindric Chromo-Hologram Portrait of Alice Cooper’s Brain lives in the collection of the Dalí Museum in Figueres, Spain. Now recognised as a trailblazing example of the artist-meets-musician collaboration, echoes of it can be seen in everything from Lady Gaga’s collaboration with Jeff Koons on her Artpop album cover to Takashi Murakami’s anime-inspired work with Kanye West. For Cooper – who at 70 is now a devout Christian – its existence is a permanent reminder of wilder times. “He was the most bizarre character I’ve ever met,” he says of Dalí, who died of heart failure in 1989, aged 84. “And yet after a while you felt very close to him. Working with him was one of the greatest moments of my life.”

One last mystery about this extraordinary episode remains – the whereabouts of The Alice Brain. “I have been looking for that brain forever,” he says with a rueful smile. “That’s my Holy Grail. Someone might be using it as a paperweight for all I know. I would pay whatever it cost to have it.” It seems like the perfect metaphor for a project that, from the outset, existed in the hinterland between genius and madness. To achieve true greatness, it seems, you sometimes really do have to lose your mind.