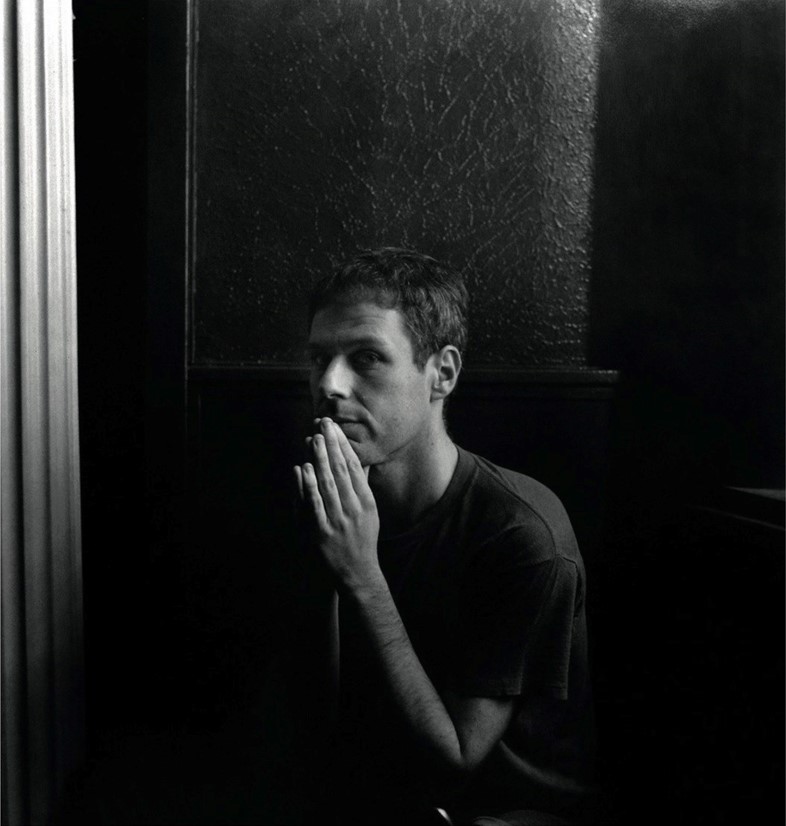

Cult Author and Anarchist Dennis Cooper on His Feature Film Debut

The American lit punk discusses his upcoming movie Permanent Green Light, which hints at the dangers and inscrutability of youth

“The cool thing about being an artist is you get to be a teenager your whole life. You never really have to give in. You’re always dreaming and believing that making something can change the world.” I’m on a Skype call with Dennis Cooper – the 65-year-old icon whom Bret Easton Ellis has called “the last literary outlaw in mainstream American fiction” – and he’s drawing a parallel between his never-ending fascination for teendom and the ethos of an artist.

“Most of my artist friends, whether it’s John Waters or Charles Ray, they’re like kids – still completely wild, funny and thinking about weird things,” explains the kind and very unassuming Cooper. “So for Zac [Farley] and I, it’s really easy to be in that place, because we dedicate our lives to making stuff. We don’t have kids, 9-to-5 jobs or wedding rings. We spend our days working on films, listening to music and making art, because that’s what excites us.”

Permanent Green Light, the feature film we’ve convened to chat about with co-director Zac Farley, is as subversive as Cooper’s most dangerous works of fiction, though it lacks any of the overtly shocking Cooper staples (killing sprees, cannibalism, necrophilia or extreme fetishists). It’s rather about Roman (Benjamin Sulpice), a detached French teen who wants to blow himself up in public, not as a grand ideological gesture or to put an end to his suffering, but for the sheer spectacle of such a disappearance. If you’re unfamiliar with Cooper’s unflinchingly honest, eerily erotic prose, you should know it tends to portray pretty, troubled young guys and the predators who want to inflict merciless harm onto their bodies. Inspired as a teen by the work of the Marquis de Sade, and wanting to tap into the dysfunctional family dynamics, reckless drug taking and rampant horniness that consumed his life, he set about writing with an absolute “purity of intent”, something he ascribes to one of his childhood heroes, renegade French poet Rimbaud.

When Cooper was 12, he visited a spot in the mountains near his California home where three boys had been raped and killed, which awakened in him something he’s since described as “an eroticised fear.” This type of frank fascination for sexual violence has permeated his precise prose, allowing the deeply humane author to explore thoughts and feelings others would never dare to, in books ranging from his George Miles cycle of novels and his Prix Sade-winning The Sluts (becoming the first American to win the prize in 2007) to his latest effort in novelistic dissent, 2011’s The Marbled Swarm. A testament to his intimidating street cred, legend has it both Marilyn Manson and Trent Reznor wouldn’t allow Cooper to pen Spin cover stories about them, fearing they’d be outed as poseurs.

Since relocating to the motherland of his favourite literary rebels (Rimbaud and De Sade, for one, but also Verlaine and Baudelaire) years ago, Cooper has ditched the novelistic form – and words altogether – to give life to animated novels using GIFs (2015’s acclaimed Zac’s Haunted House and 2016’s Zac’s Freight Elevator), perhaps as a result of “speaking French very poorly and the effect of everything around me not being clear,” he reasons. His spare time has also been spent collaborating with French playwright Gisèle Vienne, as well as visual artist Zac Farley, which explains why they’re both speaking to Another Man from Paris, following their film’s world premiere at the Rotterdam Film Festival.

“I started reading Dennis’ work when I was 17 and was immediately super obsessed with it,” recalls Farley. “It seemed like Dennis’ novels had a way of dealing with sex that was quite different.” Meeting for coffee after both had relocated to France, he and Cooper quickly began working on projects, including Like Cattle Towards Glow, about the oft-threatening sexual misadventures of assorted queer twinks and druggy teens, broken down into five tableaux. Their very first project, which remains unfinished, found them driving around Scandinavia for weeks to document the region’s many amusement parks, while also rewriting Hans Christian Andersen fairy tales and setting them in the aforementioned theme parks.

As for the spark that brought about Permanent Green Light and its foreboding sense of suburban ennui, Cooper mentions being fascinated with the story of lonely Australian teen Jake Bilardi (aka Jihadi Jake), who joined ISIS and eventually blew himself up in Iraq in 2015. Nobody could understand why he would have done such a thing, Cooper points out. “Ultimately, that has nothing to do with the film,” he explains, “but it’s this idea that he could have used this event to erase his own identity or personhood. That’s what interested us: developing a character that would have a similar idea about how to disappear but without the terrorism component.”

The premise for Cooper and Farley’s film introduces a notion perhaps much scarier than an unlikely Western recruit to ISIS terror: a person who wants to explode but doesn’t want to die, and above all doesn’t want anyone thinking he has died when he blows himself up… in public. Still with me? “I’m very interested in magicians and magic tricks,” muses Cooper when confronted about the unlikelihood of his character’s success. “The super ambitious kind – say, David Copperfield or David Blaine – who are searching for the ultimate magic trick that’s completely implausible, like making a tank or a building disappear. But there’s no commitment on their part; it’s all very ephemeral. In a way, I think of our protagonist as the ultimate magician, because he wants to create a total spectacle, which requires complete commitment, whether that be his disappearance or his death.”

Unlike most of the young men Cooper has dreamed up in his transgressive fiction, none of Permanent Green Light’s characters are objectified or preyed on by older, predatory types. In fact, none appear to even remotely think about sex, save for one lovelorn guy pining for Roman. Where the film does fit into Cooper’s larger body of work is in its deep respect for the complexities and desires that are part and parcel of the teenage experience. “The teenage years interest me because you’re perceived to be this weird interim creature, this thing that only lives for five-six years on your way to becoming an adult,” says Cooper. “As a child, you’re respected, and as an adult too, but teenagers are just seen as being this mess. If Roman was 35 years old, the audience would go: ‘that guy has mental problems’. Because as soon as you get past adolescence, there’s this ‘you have to be an adult now’ expectation. So we decided to place Roman’s quest in that weird teenage period, which is quite scary, volatile and confusing to people, because that’s when anything is possible.”

Stay up to date with Dennis Cooper-related goings on by visiting his blog.