In the wake of Perry Ogden’s new book Paddy & Liam, we speak to the photographer about Pony Kids – his stunning documentation of Dublin’s suburban horse culture, published in 1999

- TextTed Stansfield

On the first Sunday of every month, Dublin town centre would play host to an almost medieval event: the Smithfield Market. Here, horses would be bought and sold, and people from the local community would gather to meet. It was a chaotic and noisy affair and, apparently, one that smelled strongly of horse sweat, urine and dung.

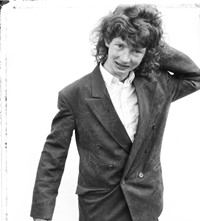

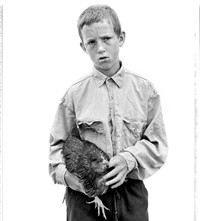

Here, sometime in the 1990s – and amid these sounds and smells – British photographer Perry Ogden met the pony kids: a mix of Traveller and Settled children from the public housing estates that circle Dubin, who owned and rode ponies. Ogden was immediately fascinated. To him, they represented a fusion of Traveller and Settled culture, old-world equestrian and modern-day youth culture. They were outsiders and – after the Control of Horses Act came into effect in 1997 – outlaws. Despised and discriminated against by mainstream society, they attracted the nickname “urban cowboys” – though they maintained they were actually the Indians.

Ogden returned many times to the fair to document the pony kid culture, photographing his subjects against a white background as formal portraits, creating images that he would later publish in a book titled Pony Kids (1999). Setting these black and white images alongside words from the pony kids themselves, this book is now a classic in outsider documentary photography and is incredibly rare.

Here, off the back of Ogden’s new book Paddy & Liam, which is launching at DSM London tomorrow, Ogden reflects on Pony Kids and how it came to be.

“I came across the pony kids at the Smithfield Horse Fair, the monthly horse fair in Dublin. I went along and it was amazing. I was introduced to this culture, these kids mainly from the suburbs of Dublin owning and riding horses.

“What captured me was their energy and enthusiasm; this meeting of Traveller and Settled culture, of this old culture of horses coming together with Nike and Adidas sportswear. And their haircuts, too. It was fascinating.

“I went to the market whenever I was in Dublin on the first Sunday of the month. I really wanted to document it, but to do it against a plain background with reflected light to capture the kids themselves; their clothes and their haircuts.

“I’d go there early in the day and set up a little studio space and then start walking around, asking kids to come and be photographed. By about 11 o’clock or midday, there would be so many people, kids saying ‘Mister, Mister, get me on this one’ or ‘get me with this dog’ or chicken or pigeon or whatever it might be.

“Later, when I went to interview the kids, they were very forthcoming and had great stories. They wanted to tell me how they got involved with horses, their experiences with them, and what was happening.

“The council was trying to stop [the culture] by introducing new legislation. It became about animal rights actually. But if they’d looked at where these kids came from, the drugs in the areas they were growing up in – heroin had been creating havoc in Dublin since the early 80s and it’s no better now. If they’d looked at the state of people, rather than just the animals, they might have been able to do something more positive.

“One of [the pony kids] died in a motorcycle crash very early on. Some went to prison and quite a few have died by now. One guy, Niall Fitzgerald, is still riding and trying to qualify for the Dublin Horse Show. I saw him towards the end of last year. It would be interesting to see where they all are now.”