In the wake of our Bob Mizer feature in the A/W17 issue of Another Man, GB Jones talks about her connection with the Finnish artist’s work

- TextAlex Denney

Pornography, the author Angela Carter once famously wrote, is “art with a job to do”. It’s a line that comes to mind for GB Jones when discussing Touko Laaksonen, the late erotic artist known to his fans as Tom of Finland.

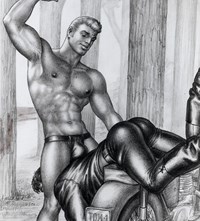

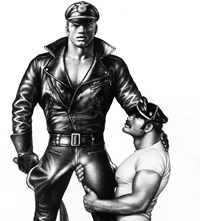

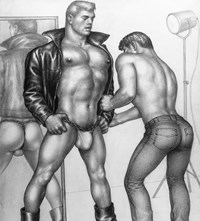

Laaksonen’s importance as a postwar icon of gay liberation is hard to overstate. An art director at a Helsinki ad agency by day, Laaksonen – the Tom of Finland moniker was coined by Physique Pictoral editor Bob Mizer – drew pictures of improbably hung, stacked-looking men in his spare time, a risky pursuit in a country where homosexuality was outlawed until 1971. “My cock is the boss,” he says in Dome Karukoski’s recent biopic of the artist, Tom of Finland, offering a frank assessment of his art. “If I don’t have a hard-on, it’s no good.”

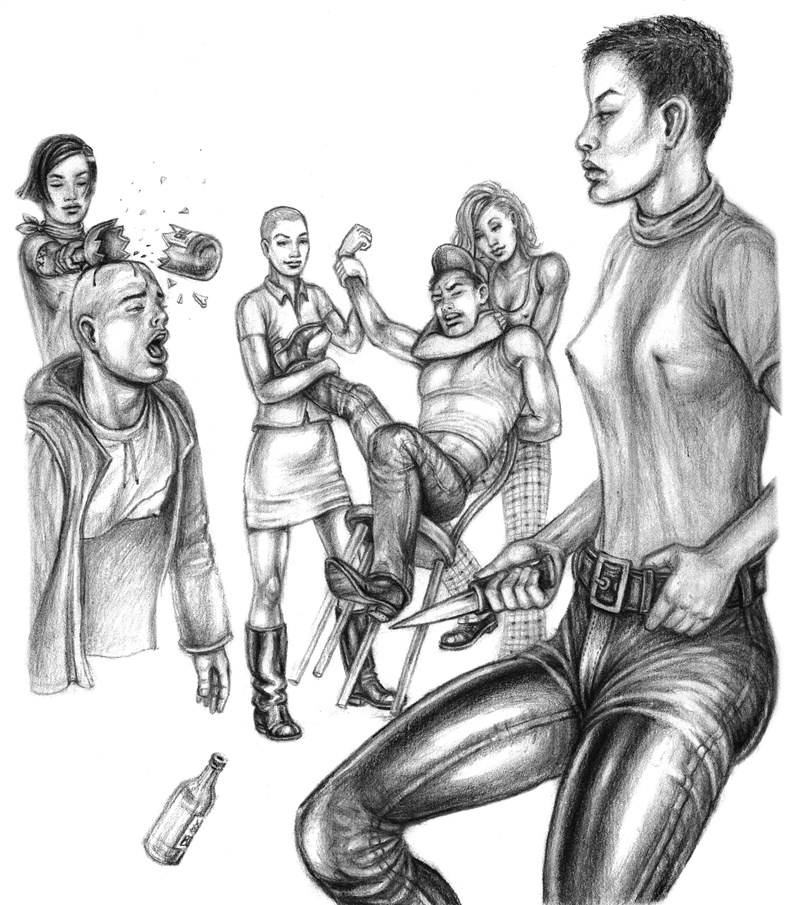

Eventually, his work found its way into the ‘beefcake’ magazines of 1950s America, where it struck a chord with the burgeoning gay subculture. It also found its way, in “dubious circumstances”, into the hands of a 13-year-old GB Jones, the Canadian artist and musician whose work with Bruce LaBruce on J.D.s fanzine set the scene for riot grrrl. Her series for the mag, Tom Girls, turned Tom’s preference for a sort of cheery-looking übermensch on its head with violent scenes of highly sexed biker chicks taking revenge on their oppressors.

The two even shared exhibition space together, when Tom Girls was displayed alongside Tom of Finland’s work in New York, a few months before Laaksonen’s death in 1991. Here, Jones talks about her connection with Tom of Finland’s art, and why, taking Carter’s quote to its logical conclusion, some kinds of pornography may even be “multi-tasking”.

“I was introduced to Touko’s work in rather dubious circumstances at the age of 13. At the time I had no idea what BDSM was, so I thought it was creepy and scary. But of course I remembered Touko’s drawings.

A few short years later, I was taken by a friend to visit a hairdresser they knew in Toronto. We walked through the salon and into the back apartment and there, on the kitchen table, was a Tom of Finland book with many of Tom’s earlier drawings from the 1950s, the pastoral celebrations of rural life. In Canada, we have a famous folk song that was once taught in schools called The Log Driver’s Waltz, so here was familiar ground – it seemed that Finland and Canada both saw themselves in a similar way, with similar motifs and myths, the same heroic log drivers on the rivers, sailors on the lakes, and lumberjacks among the tall trees. I could see a connection in this language of folk traditions.

When punk exploded in the UK, Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McClaren made t-shirts for their store Sex that used queer imagery: the ‘Cowboys’ t-shirt, the ‘Fuck’ t-shirt and the ‘Prick Up Your Ears’ t-shirt. That was the moment when queer and punk came together visually – lots of queer people were already involved in the early punk and new wave and industrial bands sonically. I wanted to expand on the connection in a really explicit way, so I came up with the idea of doing a zine devoted to Queerpunk called J.D.s. Tom Girls was one of the first things I thought of since I wanted to establish a connection to earlier publications like Physique Pictorial, but with a twist: I hoped to get someone to redo Tom of Finland’s drawings, but with women and for women. I couldn’t find anyone who would do it, so I ended up doing them myself.

I always felt, with Tom Girls, that it was a way of communicating with Tom. It was meant as both a tribute and a critique, a way of exchanging ideas. My favourite quote from Angela Carter is, ‘Pornography is art with a job to do’, and in fact, it may be doing more than one job: it may even be multi-tasking! All pornography is informed by ideology. I think the Tom Girls series makes that point very clearly – and so that whether or not one finds the drawings erotic or not depends on your politics.

What I find fascinating is how Touko constructed masculinity as a set of costumes and poses which could be put on and taken off. This was revolutionary, because men, maleness and masculinity expect to be taken very seriously in our society, (but) Tom of Finland demonstrates in his drawings that it’s something that can be played with. Lumberjacks, sailors, bikers, cops – it’s all dress-up butchness for kicks. What needed to be taken seriously, though, were the power dynamics going on in the drawings – most especially because we know that gay people are not immune to the lure of fascism. Ernst Rohm, for one, was head of the SA in Nazi Germany, and nowadays we have at least one very visible gay figure in the so-called ‘alt-right’. If the aesthetics of fascism involve the eroticisation of power itself, then we have to look at Tom’s drawings and understand that we need not accept submission to a uniform. That was part of my critique, and that’s what I tried to do with the Tom Girls.

Touko was probably more conflicted about his relationship to authority than someone of my generation. He knew he had to go against authority to live the life he really wished to live and create his drawings, and yet he’d been a part of that authority, as a member of the military (Laaksonen was a lieutenant in the Finnish army during WWII). I think that conflict is expressed in his work, and that’s what’s so interesting about it. He was living at a time when almost all visible LGBT artists had their work banned – and of course he would have been following closely all the problems that small press publications like Physique Pictorial were having, since his drawings were in them. This went on through the 1970s, all throughout the last century right up into the 1990s, when Steve LaFreniere edited a book of my work and it was banned. All the laws of every country were against LGBT people. The threat of violence was constantly in the air. But that didn’t stop Touko. He was willing to take the risks to create and show his drawings, and that, in itself, was a political statement.”