Being Mapplethorpe’s Muse

- TextTed Stansfield

He went from a humble fitness instructor to Robert Mapplethorpe’s most photographed subject. Here, Ken Moody tells his story, discusses their complex photographer-muse relationship and what it was like to be in front of Mapplethorpe’s lens

Pablo Picasso had Marie-Thérèse Walter, Andy Warhol had Edie Sedgwick and Robert Mapplethorpe had Ken Moody. Born in upstate New York in the 1960s to a nurse and a construction worker, Moody moved to the Big Apple in the early 1980s where he met the notorious photographer, already a prolific figure on the downtown art scene. It was to be a fateful meeting. A graduate of the Fashion Institute of Technology and a professional fitness instructor, Moody soon became Mapplethorpe’s most-photographed subject, appearing in many photographs which are now among the most celebrated works in 20th-century art. More than three decades after the pair met, we spoke to Moody, who agreed to tell us his story.

“Robert and I were introduced by his friend, Dimitri Levas. We both went to this gay-owned gym on Sixth Avenue. He walked up to me and proposed that I meet Robert, and handed me one of his business cards. I had just seen (Mapplethorpe’s) book, Lady Lisa Lyon, in this glamorous bookshop in New York called Rizzoli. I’d flicked through it and was amazed. This female bodybuilder… I worked in fitness, and fitness was really important to me. The way he shot her was mindblowing to me. Mindblowing. So imagine my shock and surprise at being handed the business card of this photographer, whose work I was amazed by. Needless to say, I was very, very pleased. But of course I kept myself pretty cool, though inside I was a writhing mass of delight [laughs]. I took his card, waited a day or two, and called him. We met and that was the beginning of our photographer-muse relationship.

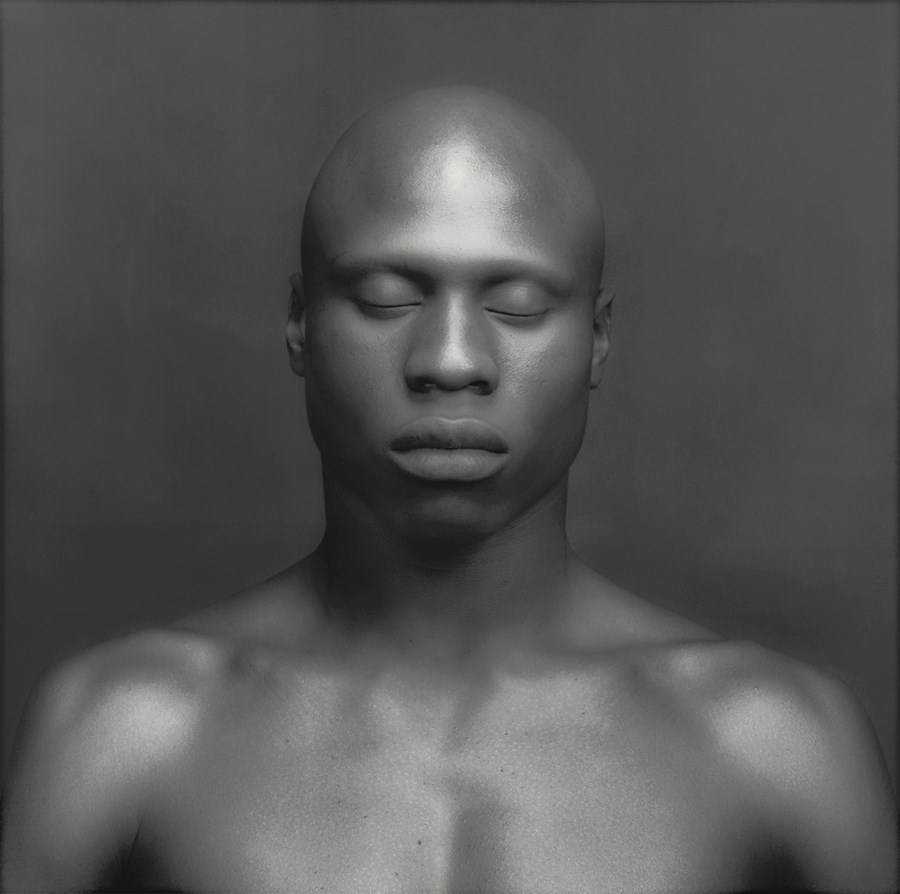

I met him at his studio at 24 Bond Street and we started shooting immediately. He asked me to take off my shirt and I sat in front of the camera. It was then that he produced one of the most perfect photographs that we ever took together. I sat facing the camera, with my eyes closed. It was so simple, so pure. I didn’t like the photograph then, but I love it now. I thought it looked like an advertisement for the condition that I have, alopecia universalis, and so I didn’t like it. It wasn’t until years later that I was able to see it for what it is: an extraordinary image.

When we met, nothing struck me as odd or terribly different or even exceptional about Robert. He just seemed like this nice white man, although he was very quiet. He was very, very professional, and I believe that’s probably because I fell outside the category of man that he was always attracted to. I knew what his tastes were, and I also knew that I was not that.

Robert was attracted to ghetto men. I was raised in the 60s and remember this TV show that summed up what we as black people were trying to do, and that was to leave the ghetto. We wanted to leave the ghetto – there was no attraction to the kind of person who comes from the ghetto, there was no attraction to being in the ghetto, there was no attraction to the ghetto, period! It was not something that anyone had ever aspired to. Consider the way I speak, my education and the way I was raised. I believe that he thought – and many people seemed to think this about me – that I was a snob, which I know turned him all the way off. All the way off. At one point he even referred to me as an ‘Oreo’. In other words, white on the inside and black on the outside. I thought, ‘Why the fuck can’t I be black and reasonably well-educated, well-read, well-travelled and speak like an educated person?’ I was never a snob, but I think he thought I was one, and therein lies the reason that we did not get along.

Photographers photograph what they love, or what they are attracted to. Look at the work of Bruce Weber or Herb Ritts – they all fetishise what they love. Bruce Weber fetishised those white boys with perfect bodies, and Robert fetishised black men. He objectified them. But I was flattered that he wanted to photograph me so much. I grew up with alopecia universalis and lost all of my hair between the ages of 12 and 16. Every single strand. So the fact that someone thought that I was beautiful was something that I held on to. I was so flattered.

I never did full-frontal nudes though. My mother was still alive at the time, and she was this older southern lady who was raised in the church. I thought if my mother ever saw my dick in a photograph, she would put me over her lap and spank me until I bled [laughs]. But also, it’s not me, it doesn’t reflect who I am. I know I would have trouble seeing a photo of my dick in a gallery or a museum, so I couldn’t really do it.

Robert and I shot together over three years – 1983, ’84 and ’85. I reckon we did it 12 times in each of those years, maybe a bit less. I remember reading on the internet that I was his most-photographed subject, and I thought, ‘Well, gosh! I guess that’s true!’ Next to Lisa Lyon of course, because he made an entire book with her.

I didn’t think it was exceptional at the time, I had no idea. I just assumed that, when a photographer found a subject that they liked, they would work with them a lot. I knew that there was chemistry between us. I knew that from the first day. I could always tell when I have chemistry with a photographer, and with Robert I knew immediately that he was going to produce incredible photographs.

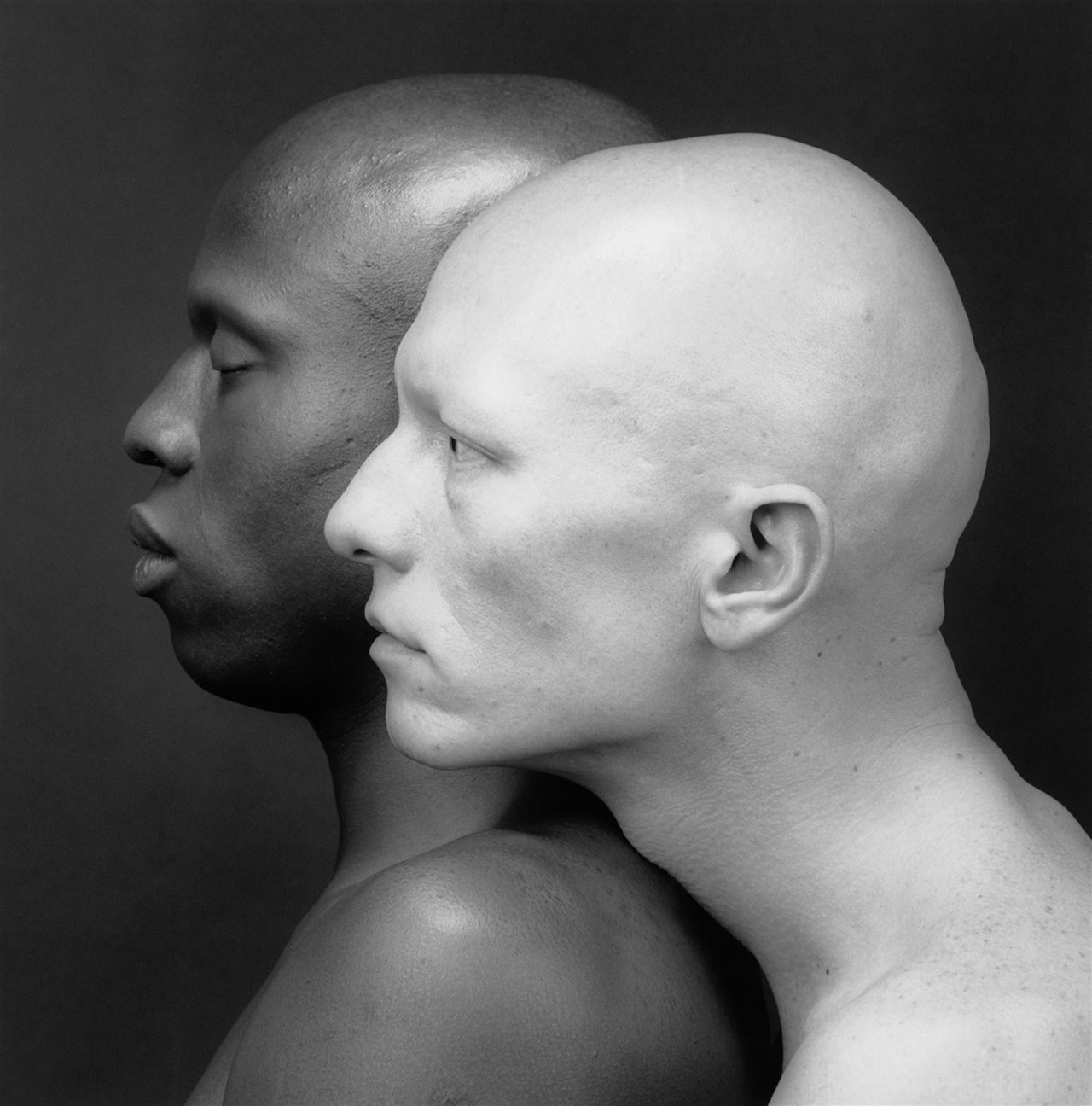

And yet I had this ‘thing’. We didn’t necessarily like each other. I don’t think that he liked me, nor did I like him. We had nothing in common. Nothing. And I was always suspicious of people who were driven by sex. I’d heard about the way that he lived. And the kind of man he was attracted to was the polar opposite of me.

Nobody told me about his death. Nobody even told me he was ill. I heard about it through the rumour-mill, which I really resented. I was angry, because we had worked together so closely. And yet nobody had thought to call Ken Moody and tell him that Robert was deathly ill and on his way out. Not only that, but nobody rang to tell me he’d died. I was invited to the memorial at the Whitney Museum, which I was grateful for. It was star-studded. They did a beautiful job.

I’m 56 now and I live the Bronx. I have type 1 diabetes which has affected my work, which has mostly been in retail. I’ve had too many insulin reactions, which leave you looking like you’ve had a bad drug trip. You don’t want to look like that when you’re dealing with the public, especially when you’re working in stores on Madison Avenue and Fifth Avenue. They attracted some of the wealthiest clients in the city. I couldn’t do it any longer, so I’ve recently applied for disability benefits. It may take six months for me to be accepted, so right now I am doing nothing, absolutely nothing. I’ve worked since I was 12 years old, I am used to working, I like working – damn this disease, I cannot be depended upon anymore. I rent a room, and there are two other men that live here and we pretty much keep to ourselves. We’re not friends with each other, but it’s a decent little apartment. So as much as I can, I try to keep up with my social life, stay in touch with friends and family that’s left.”

Special thanks to Ken Moody and The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation