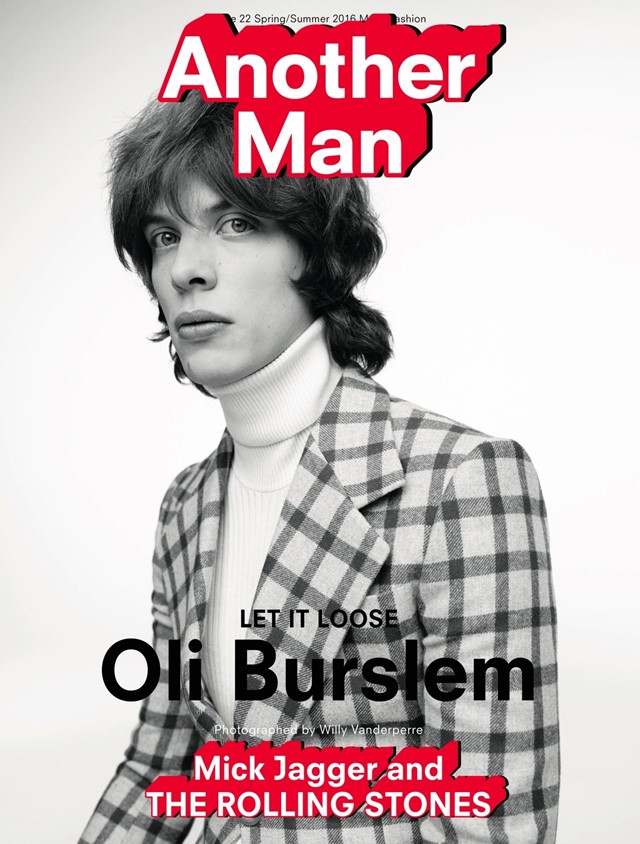

Oli Burslem

Oli Burslem MIGHT LOOK LIKE A POUTY PRETTY BOY, BUT DON’T BE FOOLED. ON STAGE AS THE FRONTMAN OF BRUTALIST ROCK BAND YAK, HE IS A CRAZED, CAPTIVATING AND SOMETIMES DOWNRIGHT DANGEROUS PERFORMER (CUE FLYING KEYBOARDS). READY TO UNLEASH THEIR DEBUT ALBUM, BURSLEM REVEALS THE METHOD BEHIND HIS MADNESS…

Oli Burslem is hard to miss. Sitting in the back booth of The Social in Little Portland Street, he is every inch the 21st-century pop star. His kingsize lips and sculpted cheekbones, shaggy locks and rangy athleticism are worthy of the young Mick Jagger. His gaze, meanwhile – steady, but otherworldy – carries the cosmic glint of every rock’n’roll starchild from Syd Barrett to Tim Burgess. Even by those exalted standards, Burslem’s looks are remarkable. When Mario Testino spied him working as a runner on a Burberry shoot, the photographer refused to continue until the singer was excused of his coffee-making duties and installed as the main model.

However, it’s when the 27-year-old starts to speak that you sense how important his band could be. “I was talking to someone the other day who said music doesn’t matter that much,” he says, nursing an afternoon pint of Guinness. “It really made me think: if music doesn’t matter, then what does? It’s not like TV, or food, or even relationships. Music has the power to help you make sense of the universe. What else does that?”

Yak are the buzz band of 2016 – and with good reason. While their peers crave mainstream success or social media omniscience, this London based trio (Burslem on guitar and organ, Andy Jones on bass, Elliott Rawson on drums) do neither. Obliquely named in honour of New York art rock icons Swans – “We wanted a name which doesn’t give too much away, we want to keep people guessing” – their online presence to date has been restricted to a series of kaleidoscopic YouTube videos, courtesy of fi lmmaker and Jesus and Mary Chain veteran Douglas Hart, and feedback-drenched live clips.

Instead, they have built a reputation the old fashioned way, via a series of electrifying live shows designed to show off both their chaotic spirit – they perform without a set list – and wildly eclectic influences ranging from prog titans King Crimson to skiffle pioneer Lonnie Donegan; folk icon Karen Dalton to irascible indie legends The Fall (they have covered songs by all four live).

It’s a no compromise approach which has been made manifest in their single releases. Debut single Hungry Heart, released last February, was a paranoiac blast of scorched earth rock’n’roll which married the experimentalist attack of Silver Apples with a nagging chorus of “Again and again and again”. If the lead track on the follow up Plastic People – complete with dazzling artwork by Nick Waplington – was a more accessible jittery blast of motorik indie noir, last November’s EP No – released on Jack White’s Third Man label – was more splenetic still.

A pulverising blast of defiance full of shrieking guitars and distorted synths, it found Burslem hollering non sequiturs (“Out of the woods/You’re all clear”) like a man just roused from a harrowing dark night of the soul. “Guitar music only really excites me when it takes things to the edge,” he says of their slow-burning progress to date. “I like music to have some dysfunctional edge. But to get to that point you have to push yourself to the absolute limit.”

In person, Burslem isn’t anything like his songs suggest. A self-confessed music obsessive – he enthuses about everyone from Malian instrumentalist Ali Farka Touré to Slade, he’s warm-hearted and witty, his thoughts tumbling out in a thick-as-tar Black Country brogue as disarming as his backstory.

Raised, as he puts it, “in complete cultural isolation on a farmyard” in the rural West Midlands, his first love was early rock’n’roll. “When I was really young I was obsessed with Elvis,” he grins. “He didn’t seem like a real person. I also loved all those really catchy 50s songs like Bobby Darin’s Splish Splash and The Crystals’ Da Doo Ron Ron. As a kid you can get on with them.”

Unhappy at school and inspired by his brother’s experiences playing drums in a rock covers band (“I would go and see them play at biker do’s, which was a pretty good grounding”), he retreated into his own private universe. “I would wander around Wolverhampton wearing bright red trousers, thinking I was Syd Barrett. At the same time, I knew I wasn’t academic, so the only chance I had of making it as a musician was by moving away.”

Arriving in London at 17, he secured a job working at legendary arts hub The Foundry in Old Street. “It was a real eye opener. I loved everything about it, from the spoken word nights to chasing rats out of the basement.” Peripatetic by nature, he drifted through a series of jobs in bars, on building sites, and at pool clubs trying to stave off boredom before he began running an antique stall at Spitalfields market. Here, Burslem’s photogenic looks and natural charisma drew the attention of high-profile customers including Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore, Bill Drummond and Spiritualized guitarist John Coxon, reigniting his own musical ambitions in the process. “I’d known Andy, our bassist, since school so we booked a room and just started playing music together. I’d always been into the Stooges and The Velvet Underground, but the most important factor was that we didn’t impose any stylistic rules on ourselves.”

Having recruited Kiwi drummer Elliot Rawson with the lure of playing “tasteless cock rock”, the trio set about ripping apart the rock rulebook at gigs around London where Burslem’s anything-goes aesthetic and brutalist guitar parts came locked into the propulsive grooves of a diamond-hard rhythm section. “I first saw them at the Old Blue Last in the summer of 2014,” recalls manager James Oldham. “John Coxon from Spiritualized had been raving about this kid Oli and he took me down there. The gig was amazing: full-on and deranged. What sets Oli apart is that he’s totally authentic. He never fakes anything or goes through the motions. He’s also an amazingly inventive guitar player, with the ability to do something completely original, like Kevin Shields in My Bloody Valentine.”

Oldham’s faith looks set to be rewarded. Recorded in London with Pulp’s Steve Mackey, Yak’s debut album – due in May, titled Alas Salvation – will propel their distorted vision into the mainstream. Like all the great debuts, it evokes its own self-contained world, non-conformist in spirit but with enough classic pop hooks to draw in the curious. If ultra-catchy Dion-inspired pop nugget Doo Wah should ensure they make it onto the daytime airwaves, it’s Burslem’s lyrics – part Mark E. Smith, part Ray Davies – which really set Yak apart.

Opener National Anthem/Victorious dares to address the austerity-torn Britain of 2016, complete with the lyric: “They pulled the wool over my eyes/No picket fence/If you sink, tough shit/You’re gonna miss the rent.”

“I was thinking about how horrible songs like Rule Britannia are,” he says when we catch up at a private party to celebrate the end of recording at The Lexington in Islington. “I hate that line: ‘We’ll never be slaves’. What a horrible sentiment. I wanted to write a song which reflected the world we’re in now. People are in desperate situations and yet no one talks about it. At the same time, I wanted the music to be really aggressive and confrontational, too.”

It’s this sense of rock’s transcendent qualities which fuels the album’s eight-minute stand-out, Roll on Baby. Built on a zig-zagging garage riff Burslem drawls: “This rock’n’roll is starting to bore the living daylights out of us all/Rearrange/Strip bare/ I wasn’t born/I wasn’t even there”, before exploding into a blaze of Spiritualized-style riffing complete with squalling free jazz saxophone. “It’s about that boredom we all feel just sitting at home,” he says. “I wanted to make a song which makes you want to drive fast, get fucked up, get crazy or whatever. That’s why playing live is so important to us. For me, the gigs aren’t about the band. They’re about everyone in the room feeling the same way and losing themselves in this wall of sound.”

Later that evening, Yak deliver the kind of performance which reminds you why you fell in love with rock’n’roll in the first place. They careen through fan favourites Harbour the Feeling and I Know What You Want and Roll on Baby before Burslem moves to the side of the stage for a mesmeric Smile. Playing the same chord over and over for five minutes in homage to My Bloody Valentine’s You Made Me Realise, it’s deliberately attritional, challenging the audience to give into the music and breaking down the structural parameters of what a song can actually be.

He ends the set by dismantling Rawson’s drum kit during a frenetic No, leaving the stage trashed amidst a wild roar of feedback. It’s both exhilarating and uncompromising, and proof that Burslem’s recurrent themes – insanity, frustration, rage, paranoia – can be channelled into songs of such vicious, serrated, hysterical quality. “Most bands are like brands, aren’t they?” Burslem commented earlier. “They might have this heavy rock’n’roll image or act as though they’re shy. But ultimately they’re all fake personas. What I’m interested in is being completely and utterly real. That’s the challenge for me. We want to take rock’n’roll to places it’s never been before.”