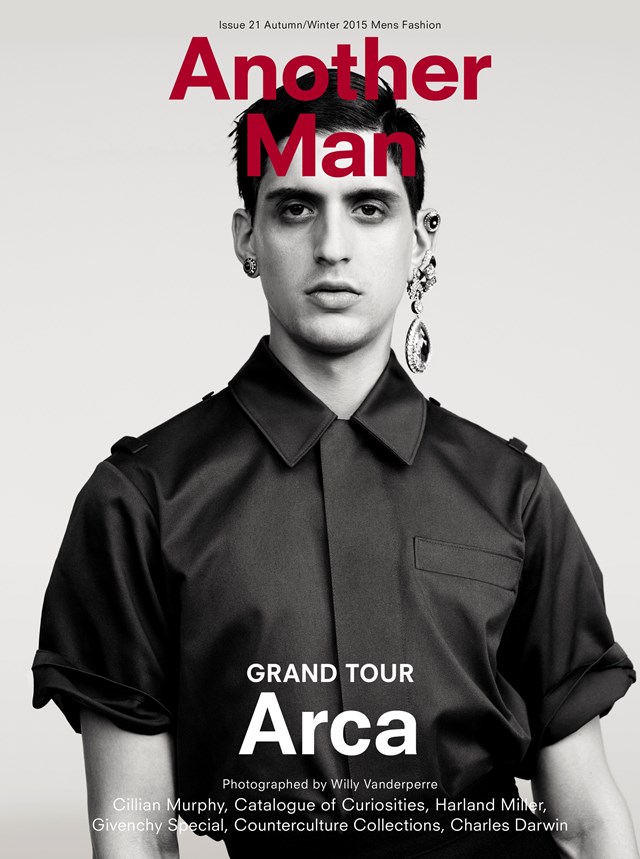

Arca

RAISED UNDER VENEZUELA’S REPRESSIVE REGIME, MOULDED IN THE BASEMENTS OF NEW YORK’S QUEER SCENE AND, FROM AN EAST LONDON FLAT, REBORN INTO A GENDERLESS DIGITAL BEING...

Arca IS AN ENTIRELY NEW KIND OF POP STAR.

Alejandro Ghersi has summoned New York’s underworld. Inside a packed venue on the Bowery, where the streets were once lined with peep shows and flophouses, the notoriously elusive musician is preparing to stage an assault on the audience’s senses. The internet might be heaving with his aggressive, sensual and, at times, almost unlistenable sounds, but up until now, Ghersi – better known as Arca – has rarely been seen in person. The crowd is restless. Suddenly, a mysterious figure clad in assless leather chaps and thigh-high platform boots emerges from the shadows...

In the flesh, Arca harnesses his transformative qualities like no other. But tonight, the 25-year-old Venezuelan-born producer is taking his shapeshifting abilities to new extremes. Under a spell of strobe lights, his moves appear vigorous and hypnotic. He’s thrusting, gyrating and body-popping against a giant backdrop of disturbing images, conceived by visual alchemist and longterm collaborator Jesse Kanda. These videos of strange, metamorphosing female bodies add another layer to Arca’s otherworldly set, pulling everyone into the outer reaches of the duo’s imaginations.

“By the time that show came around, I just wanted to scream in people’s faces,” laughs Arca. It’s several months later and he’s on more familiar ground: East London. Arca opens the front door to his home, an intimidating black barred building, to reveal a hallway lined with extreme platform shoes. “They are actually made for go-go boys, so they are really comfortable,” he confesses with a mischievous grin. “I get them from discountstripper.com – they have the most bomb boots of all time!”

For most, throwing yourself into a riotous crowd in eight-inch heels is the stuff of nightmares. But Arca’s world is all about submitting to various states of discomfort. “People want to be yelled at,” he says, settling into his studio. “Every time I do that one track Sinner, I just want to destroy everything. It’s crazy! I don’t know what the fuck is going on. The lyrics are about brute force, blunt trauma, a woman having an attack of hysteria – but an empowered, liberated one. It’s all improvised. After the Bowery show, someone tweeted me saying I was screaming ‘cocksucker’ in Spanish. I was like, ‘Oh my god. I don’t even remember doing that!’”

Arca has already lent his dark soundscapes to several era-defining musical works – Kanye West’s Yeezus, FKA twigs’ EP2, and, most recently, as co-producer of Björk’s new album Vulnicura – but it wasn’t until the end of last year, with the release of his debut album Xen, that he truly emerged as one of the most vital outsider voices of a generation. Whether he acknowledges it or not, his work is a lifeline to the marginalised everywhere.

Embracing these feelings of isolation is something Arca attributes to his childhood in Caracas, Venezuela. “I didn’t meet another openly gay person until I was almost 18. So, growing up I was like, ‘Ok, I need to sharpen my abilities to hide all of these feelings’. I equate a lot of my wanting to be as honest as I can in my music, or how willing I am to confront something really messy, with that. Venezuela is a place where the most inhumane things happen every single day. There’s no toilet roll right now. Diapers and antibiotics are being rationed. It’s fucking insane.

But, the thing is, no one wants to hear about a country that’s been in political turmoil for more than 15 years. It’s like, ‘Oh, Venezuela is still crazy. In other news...’”

With the constant threat of violence and the cultural prejudice surrounding his own sexuality, Arca found an escape online. “I figured out that there was space for me to think differently by being connected to the internet,” he explains. “In hindsight, I laugh at myself: I was 15 years old, Venezuelan, closeted but wanting so badly to be gay. My parents were divorcing in the messiest way and there I was making IDM and playing a monk on Guild Wars. And I was chubby! I look back like, damn weirdo. But I love that world, that world is so endearing to me.” He found unlikely role models in the fantasyland of video games, citing whip-lashing Quistis Trepe from Final Fantasy VIII, voodoo priestess Lulu from Final Fantasy X and sultry assassin Æon Flux, as personal favourites. At the same time, he discovered Grace Jones, Janet Jackson, Björk, Kitty (“the female Slipknot”) and Aphex Twin (whom he simply describes as “mother”). However, disappearing into the virtual world wasn’t a permanent solution. Something needed to change.

“After 17 years of paralysis and not moving I was like a bat out of hell – I just wanted to morph,” he explains. It was in New York’s genderqueer underground that he truly began to metamorphose. Stumbling across a flyer for GHE20G0TH1K – the radical club night founded by DJ Venus X – he became immersed in a scene that was subversive, explosive and celebrated extremism in self-expression. With a notorious no-photo policy, the night was a playground for sexual experimentation, soundtracked by a mashup of musical genres from reggaeton to Angolan afro-house. It ignited a new subculture where, in Venus X’s words, “crusty punks, black lesbians and street kids were in the same room, at the same time”.

“That party changed the way I thought about music,” maintains Arca, who at the time studied audio engineering and record production at NYU. “It was the crushing together of extremes – I felt like I was home. I probably went to three or four of them without even speaking to anyone! Someone offered me cocaine, I thought someone was hot, but I didn’t talk to them… I couldn’t even drink yet! I would stay and just listen to the music until I got sleepy – I usually had class the next day.” One night, he plucked up the courage to talk to Shayne Oliver, the founder of cult label Hood by Air and an influential part of the GHE20G0TH1K movement, and so began a long-term friendship. “I would go as far to say that he birthed that whole scene in New York,” says Arca. “Shayne was in the shadows controlling everything like a witch, singing through headphones on a shitty sound system, coming alive. When he started dancing – ask anyone – the whole room would just freeze. What Shayne does is a threat to some people and a complete inspiration to others. He’s that. I call him mother. He helped raise me.”

For Oliver, who describes Arca as his “most mischievous daughter”, GHE20G0TH1K was a place for people to “express their wild sides”, and this spirit now extends to Hood by Air’s gender-fluid collections: “We’re making it normal to be abnormal,” explains Oliver. Even today, on a rare afternoon off, Arca is clad in Hood by Air, wearing dominatrix-style stacked boots and a large padlock choker. “I’ve never mentioned this publicly, but we made an album together,” he reveals (Arca also walked in the brand’s S/S16 show wearing a pearl-encrusted mouth gag). The details of the forthcoming collaboration, tentatively titled WENCH, might be under wraps until the end of this year, but Oliver lets slip that it’s as if “someone is whispering dirty words to you in Latin”. For him, working with Arca was “like having a friend with benefits... the music would get so raunchy and lusty. Then the music would stop and we would go back to being mother and daughter.”

Arca’s solo work is fuelled by an undeniable sexual pulse. You can feel it in the throbbing beats, lingering pauses and melted soundscapes; at times, it’s more explicit. Case in point: Broke Up, from his 2012 EP Stretch 2, which features distorted breathy vocals alluding to penetration (‘Hold on push in pull it out / It’s too much for me to take / It’s too much for me to take’). “If I’m in a sexy mood and thinking about what turns me on, I’ll make a song about it,” he says. “It’s not like I have an agenda. But, yeah, that song is about bottoming. It’s a very real thing that every gay man grapples with in different ways. I love twinks. Bottoming is fab and so is being on top – I love all of it. Basically everything comes down to being honest and standing by that. If that’s confrontational, then that’s a problem with the environment.”

Arca uses the disorientating nature of his music to wake people up to new experiences. “It’s about putting the audience into a mental state they are not normally in,” he explains. “Say right now, if the ceiling crashes in on us, there would be this half-second window when we’re like animals and we’re adjusting. That moment is gold to me. It’s a fertile moment because you’re not in your routine. It’s this unknown state where the rules aren’t the same.” It comes as no surprise that he cites filmmakers David Lynch and Alejandro Jodorowsky as key influencers; in particular, Jodorowsky’s tomes The Dance of Reality: A Psychomagical Autobiography and Manual of Psychomagic: The Practice of Shamanic Psychotherapy. “Those books got me through a really difficult time,” he says, “and make up a lot of the language I use to talk about the subconscious as this throbbing thing that is constantly saying stuff that most people pretend not to listen to.”

“Pretty much everybody is raised with some feeling of dysmorphia, either with their body or how they have to perform within their gender,” he continues. “Everyone has to unpack it at some point and making Xen was about doing that in a very celebratory and sensual way.” The visual manifestation of Xen, as the sexualised but often gender-ambiguous character who grinds its way through many of Jesse Kanda’s videos, is one of the most talked about mysteries in Arca’s work. Many consider Xen his female alter ego but, for Arca, it’s more complex. “It’s definitely a feminine aspect of my personality but, at the same time, it doesn’t feel right to call Xen a woman. When I call her ‘she’, it’s just a reaction to the fact we live in a patriarchy. Xen is supposed to be unchained and untethered by gender, and if there was a word to express that, other than she, I would’ve used it.”

Perhaps the most surprising thing about Xen is that the character has been in Arca’s head since he was eight years old: Xen was the pseudonym he used playing video games, it’s how he signed his diary as a child, but it was Kanda who gave it a body. “If it wasn’t for Jesse, I would have never extracted that,” he admits. “I can’t imagine what my music would sound like if Jesse wasn’t part of my life.”

Kanda, who is self-taught and met Arca on deviantart.com over a decade ago (he was 15, Arca 13) takes Arca’s sounds and transforms them into visual form. “It would be impossible to describe exactly what I draw from Alejandro because we’re so entangled in each others’ lives,” he explains. “Most of the time the work just happens... We don’t talk about it till afterwards. It’s very liquid and free. That’s what makes it special, and that’s why Xen being vague and amorphous works so well.” Previously, Kanda’s videos – beautiful and repulsive in equal measure – could only be experienced online but, at the end of last year, the duo decided to incorporate them into an immersive stage act.

“For the first show, no one had any fucking idea that I would be on the microphone or that I would be half-naked,” says Arca of his live debut at London’s ICA in November 2014. “People want to know how much of a risk you are going to take, how much you’re going to cut open your stomach and spill your guts out.” That’s exactly what Arca and Kanda did – and Björk, who spent that year working with Arca on her new album, was there to witness the event. “I was so excited for them!” she says. “Alejandro has this crazy emotional depth which is rare for such a young person… He’s the real thing and he’s going to be around for a long time. Just hold your breath, the best is yet to come.”

Arca heads upstairs to his bedroom. “Sorry, it’s a little messy!” he shrugs. To anyone who’s seen the webcam-style images he used to post on Soundcloud (arca1000000), the room is instantly recognisable. Today there appears to be a pair of slinky black stilettos hanging from the ceiling but before he can explain how they got there, Arca starts trawling through his rail of clothes. “This harness is really cool,” he says, pulling it out from a collection of other flesh-revealing ensembles. “Most of the time the gay leather ones are really thick and macho, but I got this one at Comic-Con in New York! It’s the opposite. It’s for role-playing, but not in a sexual way, more like, ‘We’re going into the woods and you’re a wizard and I’m a sorcerer…’ You know, like that!”

On and off stage, Arca fearlessly experiments with his aesthetic. “It’s not about a wig or a bra,” he is quick to clarify. “It’s about this other thing. It’s about being really subtle, but also ridiculous.” Next, he pulls out those assless leather chaps. “They were from a Salvation Army in Portland, of all places. No one wanted them; they were $20. They’re crazy!” He begins undressing, swapping his white sequined halterneck for a black backless top he wore briefly on stage at his New York show. “This is one of my favourite Hood by Air pieces. It’s a bit apron, a bit conservative businesswoman! I feel really elegant in it.”

A few weeks later and Arca is busy conjuring up another live experience. This time inside St John’s Church in Hackney, where he’s covered the entire space in 55,000 white rose petals. “They all had to be sprayed with flame repellent substances otherwise it was a fire hazard!” he laughs down the phone the following day. “But it made everything really magical. We really wanted to make use of the emotional weight of the space.” If the New York show was visceral, then this was something more spiritual. “When I first put the idea of a show together in my head I didn’t imagine doing it over and over again. If you do something too much you lose the magic. For me, it’s about finishing a story when there is nothing left to be said, otherwise you just exhaust the poetry. It’s a matter of that. When that happens, Jesse and I will go back to the drawing board and do something that excites us again.”