Jack White

Jack White is in the middle of explaining his fascination with the number three. He is starting to sound neurotic, and he knows it. “That number is just perfection to me,” he says, shifting in his chair. “It’s everything you could hope for in symmetry. It’s poetry. It’s God-like.” This morning, at the shoot, the photographer asked him to hold five roses for a picture. He couldn’t. “Because three roses are better for me. I can think that way: left, right and centre.”

Sat behind a chaotic desk at Third Man Records – his new centre of musical operations – White scans his office for something to illustrate his logic. “Take that,” he says, clicking his f ingers and pointing to a 130-year-old wooden music machine from Switzerland, a gift from his wife, the English supermodel Karen Elson. “It has three drawers to hold the discs and the top has three holes on either side of the cylinder. If you keep going, if you keep perpetuating it, it just becomes more and more perfect.” Satisfied, he sits back and sparks a gas-cooker lighter for his cigarillo.

Whatever the thinking behind it, the number three captivated White long before he strutted into the spotlight, plugged in his Gretsch guitar and with one divine, charged riff converted 90s techno kids to the raw power of blues music. John Anthony Gillis was 15 and doing a three-year upholstery apprenticeship with family friend Brian Muldoon when he noticed that three staples were used pin fabric – something about their neat III formation resonated with the teenager. Six years later, he started his own upholstering company in his native southwest Detroit and called it Third Man, because he was the third furniture restorer on the block and a big fan of the 1949 Orson Welles film. “My whole shop was three colours: yellow, white and black,” he says. “I had a yellow van, I dressed in yellow and black overalls only and all my tools were yellow, white and black.”

He introduced another three-colour policy when he formed The White Stripes with ex-wife Meg in 1997; this time red, black and white: “People thought we were being ironic but I was like, ‘Fuck you! This isn’t ironic… I fucking mean it.’” For the entirety of their sell-out Get Behind Me Satan tour in 2005 he went by the name “Three Quid”. He subsequently released a limited edition Triple Inchophone, a rare record player for three-inch vinyl. And his name appears as John A White III on both his business card and off ice door. He isn’t sure exactly why he is so fixated with everything three but “it’s not about numerology or some obsessive compulsive disorder,” he explains. “It’s just something to keep me grounded, no matter how things go off the chart.”

White’s magic number has served him well. He’s in three headlining acts; his latest, The Dead Weather, was formed in January 2009 with The Kills’ frontwoman Alison Mosshart and two members of his other supergroup The Raconteurs, guitarist Dean and bassist Jack Lawrence. He’s of the most in-demand producers the world. He’s the boss of his own record label. He’s an honourary member of Nashville’s Music Business Council. And the father of a four-year-old girl, Scarlett, and a two-and-a-half-year-old boy, Henry. “Juggling everything is easier than I thought it was going to be,” he says. “I don’t work for the sake of work. I just try and keep myself busy and a balance kind of happens. But in the last 15 years or so I have felt that I just don’t have enough time to do all the things that I want to do.”

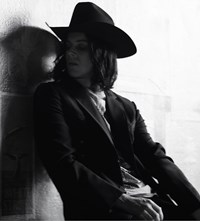

He apologises for the tomb-like temperature in the room and buttons up his brown suede cowboy shirt. White has a look of Benny & Joon era Johnny Depp about him: it’s the hair, cheekbones and alabaster skin. The 34-year-old’s relentless workload hasn’t put any worry lines on his brow; in fact, he could still pass for a teenager – and a hyperactive one at that. Throughout our hour-long conversation he talks fast – his Detroit accent smudged by a Tennessee twang and the odd British vowel, courtesy of Elson – punctuates his sentences with wild air-stabs and cackles like a nervy hyena.

He laughs a lot, even when he isn’t joking. Half way through a running commentary on the objects in his off ice – a stuffed giraffe’s head from Texas, two art deco wall lights salvaged from a cinema in Pennsylvania and a framed blow-up from the only known photograph of Charley Patton, the “Grandfather of the Blues” – White suddenly stops. “Don’t look too closely in here,” he says. A giggle is followed by... a serious but, mercifully, short-lived stare.

Of Polish descent and raised a Catholic, White – the youngest of ten children (seven boys, three girls) – grew up in Detroit’s lower-middle-class Hispanic district, Mexican town. His father Gorman Gillis and mother Teresa both worked for the city’s Archdiocese, as the janitor and the cardinal’s secretary respectively. He was a devoted altar boy “with short hair and braces” and vividly remembers at the age of 12 meeting the late Pope John Paul II – “He hugged me… I didn’t hug him back because I didn’t know you were allowed to." White was all set to attend a seminary in Wisconsin and puruse his dream of becoming a priest. "But at the last second I thought, 'I'll just go to public school.' I'd just gotten a new amplifer in my bedroom and I didn't think I was allowed to take it wit me."

Brian Eno – pop pioneer and fellow lapsed Catholic – recently said, “If you grow up in a very strong religion you cultivate in yourself a certain taste for the intensity of ideas. You expect to engage with ideas strongly.” It’s not a massive leap to see why folk and blues music became White’s calling. “I’ve got three fathers,” he says, “my biological dad, God and Bob Dylan.”

He taught himself drums at five years old but didn’t pick up a guitar until he was 14. 12 years later Rolling Stone ranked him No 17 in their 100 Greatest Guitarist of All Time poll, and, last year, his guitar hero status was immortalised when he appeared alongside Jimmy Page and The Edge in the Sundance hit documentary It Might Get Loud. At weekends, while his classmates were out dancing to house and hip hop, he was honing his production skills, recording cover versions of his favourite blues songs – “Grinning in Your Face” by Son House and Blind Willie McTell’s “Lord, Send Me an Angel” – on a four-track reel-to-reel machine in the family’s attic. It was clear to everyone around him that White was on a mission.

When asked what the blues, with its stories of poverty, hardship and suffering in the Depression-era South, meant to him growing up in America’s Motor City during the 80s, he says, quite simply, “the truth”. To him, blues isn’t a sound; it’s about a heartfelt, engaging and honest feeling. He thinks Jay-Z is as much a modern day bluesman as he is, and that the blues is the one element that unites the diverse artists signed to Third Man Records.

He turns his Mac screen around, clicks on to his label’s website and – suddenly sounding more like an excitable fan than the company chairman – runs through the roll call of eccentric releases. A Glorious Dawn, the voice of astronomer Carl Sagan from his 1980 TV series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage set to a space-age synth – “I listened to it 100 times in a row when I f irst heard it.” A“Spoken Word-Instructional Record” on fame by legendary figure BP Fallon – “He worked at Apple Records, toured with Zeppelin and was T Rex’s manager.” British female folk duo The Smoke Fairies – “I listened to their 45 at breakfast with my kids and thought, ‘They play guitar like they’re playing banjos.’” And a 15-strong troupe of Nashville bus drivers called Transit who “write songs about riding the bus… Incredible!” All blues, he says, all about truth.

Time, then, to raise the sticky subject of Mildred And The Mice, another act on Third Man Records. Online forums are rife with rumours that Mildred is, in fact, Elson in a black wig and not, as his website would have us believe, “a mysterious goth milquetoast” who gave an impromptu audition in a Kentucky hardware store and was signed on the spot. The story goes that “her mother dropped her off at Third Man studios and waited patiently in a Winnebago outside until Mildred was done recording” and that she “hasn’t given the staff an age or address”.

So, are Mrs White and Mildred one and the same? “How dare you say that!” he gasps, feigning shock. “Mildred has got a new calypso song I’ve just heard.” Is that a “no” then? “That’s a ‘no’ to it being her own person.” So we can assume Elson and Mildred won’t ever be spotted in the same room at the same time? He smiles but remains tight-lipped.

White might talk a lot about the truth: he worries that people think he is “all about control and not about the art, and the truth”; and it’s what he is searching for on a daily basis, whether he is making music, hanging out with friends or, apparently, “what we’re doing now”. But he also has what is best described as a playful relationship with it. He loves to twist, exaggerate and, on occasion, simply invent. To him, spinning a good yarn is all part of being a showman – he’s in a band called The Raconteurs, after all. In the press release for The White Stripes’ 2005 album Elephant he inserted “a joke” about how the band wouldn’t use any studio equipment made before 1963. And, during our meeting, he still affectionately refers to Meg as his sister, even though a marriage certificate from 1996 and divorce papers f iled in 2000 appeared online years ago. I remind him of a quote from his first ever NME interview – “I like things as honest as possible… even if sometimes they can only be an imitation of honesty.” He smiles, nodding, “Everybody has got a take on how they perceive things and whether it’s authentic or not.”

White first came up with the idea for Third Man Records in 2001. He was looking for “an insurance policy against bad contracts with record labels” but didn’t have “a physical institution” to house it. Back then he was still in Detroit and still at the centre of the city’s small garage rock scene, recording 45s for friends’ bands like The Greenhornes in his living room and putting them out on local imprint Italy Records. But everything changed when The White Stripes’ White Blood Cells album went gold. “After that, it was a constant fight because the Detroit music scene was all about, ‘I don’t think you should be on the cover of Rolling Stone.’ But, you know, I never said, ‘I don’t want to be famous,’ or ‘I don’t want to share my music with millions of people rather than a roomful.’”

So, in 2006,White made the move to Nashville, because “people here don’t care about ‘cool’, ‘hip’ or any of that bullshit, they’re all about getting your face on the side of a billboard, which suits me just fine.” Bizarrely, it “felt exactly like Detroit”. He recalls Jeff Evans, from Memphis band 68 Comeback, telling him how Detroit is actually a southern city in spirit because of a ley-line that runs straight up the country, connecting New Orleans, Memphis and Detroit. White admits Evans’s theory isn’t geographically accurate, but he enjoyed the idea. In the event, he found the peace of mind he was looking for in the Music City.

In December 2008, he also found a building. “It’s a strange spot in town,” he says. “The path next to us was the track from the Mission to the methadone clinic. But they just closed it off so you’re missing all the real interesting characters… It was a shell when I bought it but three months later I’d designed the whole place.” Even the lighting in the toilets? “Yeah, everything,” he nods in a slow, as-if-you-need-to-ask way. That would explain the cartoon-like palette throughout – “It’s like something from a Dick Tracy comic” – and the exotic decorations dotted everywhere: shrunken heads, African tribal masks, a skeleton puppet and two stuffed ducks.

Unlike the interior, the concept is simple. White describes Third Man as a “one-stop shop”, where he can manage the label, direct all the promotional material for its artists – from shooting portraits in the blue studio at the back, to designing the cover artwork – and sell the final product in a tin-ceilinged record store at the front. Apart from the recording sessions and vinyl pressing, which are done within “a three block radius”, the entire mic-to-till process is carried out under one roof and, crucially, takes a matter of weeks.

“I like to work fast,” he confesses. “It’s a great way to eliminate over-thinking.” The White Stripes’ last album, 2007’s Icky Thump, famously took less than three weeks to record: it was their longest production to date. He has just recorded 15 songs in three days for a second album with The Dead Weather. That said, even White admits getting Third Man Records up and running was “pretty hectic” – the blue paint in the studio was barely dry when The Dead Weather previewed their debut single “Hang You from the Heavens” in front of 150 music journalists.

“Jack sees everything through,” says The Dead Weather’s lead singer Alison Mosshart down the phone a few days later. “That’s just how he is: he does every idea his brain has – and every single day he has ten more ideas. One minute he’s talking about starting a record label and the next the building is finished. He’s like a really fast moving train.”

White has no intention of slowing down anytime soon. “I just don’t do anything halfway,” he explains. “It’s the kind of thing that Priscilla Presley said about Elvis; he never did anything halfway – if he bought you a present, he bought you a fucking Cadillac. That’s a really inspiring thing. You should mean everything you do and go all the way.” His mind darts back to the building we’re sitting in. “Once you create the place then things just start happening. We’re on our 25th record now. That’s 25 records that wouldn’t exist if this place hadn’t happened.”

Five years ago he produced country music legend Loretta Lynn’s album Van Lear Rose. Rolling Stone voted it the second best album of the year and Lynn now refers to White as her “friend forever”. He has just completed an album for Wanda Jackson, the 72-year-old “First Lady of Rockabilly” and Elvis’s ex-squeeze. “She came in last week,” he beams. “She’s an incredible kickass Southerner. I fixed her hair; we took some photos in the blue room; went to the studio and recorded a single. The artwork is done, the song is being mastered tomorrow and it’ll be out in a couple of weeks. Bam!” He slaps his desk and takes a man-size drag on a second cigarillo.

Bigger names and bigger building aside, White is the same producer he was back in Detroit: fast, exacting and hands-on. Jack Lawrence, the bass player in The Greenhornes and now The Dead Weather, hasn’t seen any change. “His enthusiasm has always been infectious,” he says down a bad “Jack understands how to capture a moment. His greatest talent is knowing exactly what is needed at exactly the right time. It’s second nature to him.” Putting it into practice is another story, judging by White’s description of the intense 14-hour days he spent at the mixing desk for The Dead Weather’s debut album Horehound. “We did it by hand. It took three guys with me saying, ‘Okay, more tambourine. Here comes the bridge part, hurry up and put the reverb on the snare.’ That’s hard to do. We’d mess it up over and over again. Nobody does it like that any more. The music industry don’t care and just say, ‘Why are you bothering? You can mix it on computer now. Make it easy on yourself.’”

But when it comes to music, White has never been interested in the path of least resistance. He imposes time and equipment restrictions on recording sessions with The White Stripes; confines himself to pounding drum skins in The Dead Weather (“I’m just sitting there so it’s really challenging for me”); and, in the midst of the digital revolution, insists on making vinyl releases a top priority for Third Man because “sometimes the new way of doing things is not the right way”.

“I come from a different outlook on art where the struggle is everything,” he says. “And if that struggle doesn’t exist then you have to make one. Art is very much rooted in struggle and when it’s not, it’s just disposable. I mean, other than the actual struggle, what’s that interesting about it.”

As anyone who has witnessed White on stage will confirm, “struggle” is at the heart of his live performances. “What’s going on in my head at that moment feels vicious,” he says. “My mind is in attack mode. It feels provocative and antagonistic to myself. Iggy Pop attacks the crowd but I’m turning on myself. It has to be a harsh thing.”

So, are music and enjoyment mutually exclusive for him? He frowns, toying with the word “e-n-j-o-y-m-e-n-t” in his mouth. “Happiness is a scary word for me,” he finally admits. “It’s like the word ‘fun’ when it comes to creativity. I don’t know what to do with it when people say, ‘We had a fun show,’ or, ‘Did you guys have fun recording?’ I don’t know what that means. Am I supposed to be having fun, laughing and high-fiving Alison when we’ve finished recording? I don’t know. It’s strange to me.”

Our time up, White stands, straightens his high-waisted black trousers and stubs out his cigarillo in a flip-top ashtray. “Thanks man, that was good,” he says, stretching his back. Walking to the door, he talks about a new White Stripes album “happening sooner or later” after a recent call to Meg, and his plans to stage 30-minute rock shows at Third Man for local kids at weekends. “We could charge a few dollars and sell virgin drinks,” he suggests. “It could be…” Fun? White – artist, entertainer and provocateur combined – stops in his tracks and chuckles to himself.