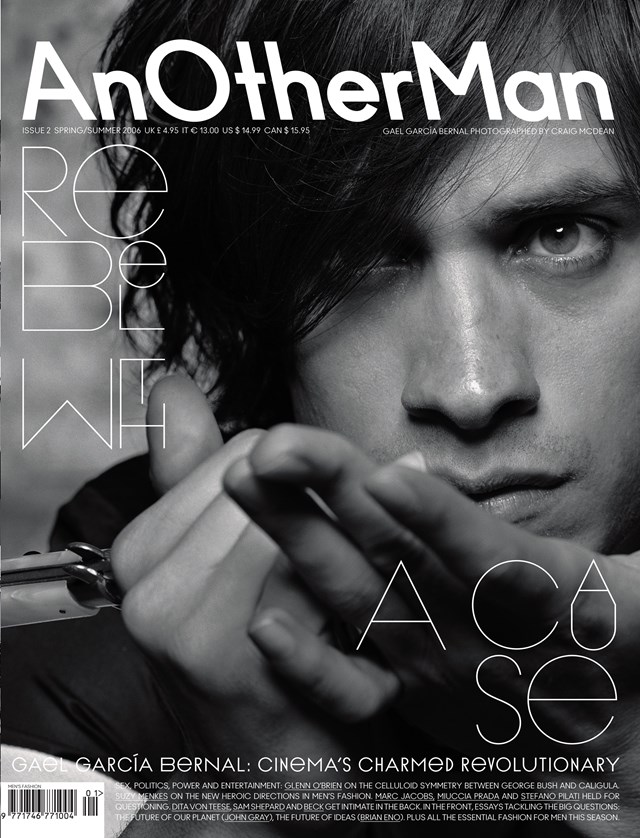

Gael García Bernal

He played Che Guevara in The Motorcycle Diaries. He made a stunning drag queen in Bad Education. Now he’s a confused young Parisian who can’t distinguish between dreams and waking-life in The Science of Sleep, Michel Gondry’s latest mind-warp of a movie. He’s worked for some of the world’s top directors, from Pedro Almodóóvar to Walter Salles. He’s fiercely political, a true film lover, and an actor who genuinely puts his art before his bank balance. He’s also a powerful force behind the new wave of filmmaking in Latin America. And Gael Garcia Bernal is still only 27.

Last night, Bernal was knocking back drinks and dancing late into the night at a house party in Greenwich Village. The morning after, he’s sitting in a small diner in downtown Manhattan, talking spiritedly about the disastrous effects that globalisation is having on rural farmers in his home country of Mexico.

“It’s getting to the point where it’s going to implode,” Bernal warns, knocking back a coffee. “The people who will be affected will be the poor. The countries who are going to get fucked up are the poor ones. It’s going to lead to civil wars.”

The more you speak to Bernal, the more time you spend in his company, and the more of his friends and collaborators that you speak to, the more you begin to understand that there’s something unusual about this young actor. There’s a refreshing, even old-fashioned, seriousness to the way he approaches his life and work. He’s unusually engaged – politically, culturally and socially – in a way that isn’t awkward or mannered. He’s hungry to learn, to work with the right people, to do the right thing, to make a difference. There’s a natural, confident ease in his commitment to cinema, politics and the world around him. If all this makes him sound too earnest, it shouldn’t; he’s as comfortable sniggering about beach parties in Brazil as he is dissecting politics. It’s all one life to him.

Bernal first grabbed the attention of the art-house crowd in 2000 in Alejandro Gonzáález Iññáárritu’s Amores Perros, an extreme story of three lives that collide in one car crash amid the chaos of Mexico City. He was 21. In the following year, he filmed the sexually charged road movie Y tu mamáá tambiéén, which made him, alongside good friend and co-star Diego Luna, Mexico’s most in-demand young actor.

“We had finally discovered a new face,” remembers Carlos Cuaróón, writer of Y tu mamáá tambiéén and brother of the film’s director, Alfonso Cuaróón.

“Here was a new young actor who could sustain emotion in a very different way. After seeing Gael in a short film a year or two before Amores Perros came out, I remember calling my brother and saying to him, ‘Man, you have to see this guy.’ He was like, ‘Yeah, thanks, I’m busy right now.’”

A year or two passed before Alfonso saw Gael in action. “Alejandro Gonzáález Iññáárritu is a friend of ours and he showed Alfonso an early cut of Amores Perros,” continues Carlos. “That was the moment when Alfonso said, ‘I want that guy!’ I was on the telephone saying, ‘I told you so!’”

Since then, Bernal has played a youthful Che Guevara in an award-winning performance for Brazilian filmmaker Walter Salles in The Motorcycle Diaries, a fox of a transvestite (and according to one critic a “dead ringer for Julia Roberts”) for the Spanish auteur Pedro Almodóóvar in Bad Education, and opposite Charlotte Gainsbourg in French director Michel Gondry’s latest movie, The Science of Sleep. It’s an impressive roll-call of collaborators. And still not one Hollywood movie in sight.

“I think Tijuana is the closest I’ve ever got to Hollywood,” Bernal jokes as we talk about the three months he recently spent on location in the notorious Mexican border town for Alejandro Gonzáález Iññáárritu’s latest film, Babel. “It sounds like a really bad tragedy, doesn’t it? The Closest I Ever Got to Hollywood Was Tijuana!”

Carlos Cuaróón agrees that Bernal’s acting path has been remarkable. “The really crazy thing about Gael is that he’s probably the most famous Mexican actor nowadays, but he still hasn’t done a Hollywood movie. He chooses his projects very intelligently. He picks them because he likes the director or because he thinks the script is amazing or because there are other interesting actors in the film. Usually, people become famous across the world because of Hollywood movies, he hasn’t had to go that route.”

Bernal’s commitment is thrown into sharp relief when he talks about his move to London to go to drama school at the age of 17 a decade ago. He was shocked by the country’s apathy to politics and culture. He expected the Rolling Stones, the Marquee Club and arthouse cinema. Instead what he found were the Spice Girls, Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels, and students who would rather sit drinking in pubs or subject themselves to pharmaceutical testing than attend a political rally.

“I found it difficult coming from Mexico,” Bernal explains. “In Mexico, there’s this feeling that everything you do has a political complexity. Which it does. Whatever you do, whoever you say hello to, whichever part of the neighbourhood you go to... Everything has this huge political complexity, as well as social, emotional and sexual.

“I think my attitude also has something to do with my family. They work in the theatre, underground theatre, so maybe I was pretentious, or snobbish perhaps.”

Bernal’s teenage years coincided with a tumultuous time in Mexico. The country was emerging from what he labels “an old tyrant democracy”, and the Zapatista movement in Mexico’s southern state of Chiapas was rising up against the government. Street demonstrations were part of everyday life. Bernal and his family lived comfortably in Mexico City – his mother is an actor, his father an actor and director – but like many kids of his age he was swept up by the energy and sheer excitement of the capital’s mass support for the Zapatistas.

“That movement polarised the country, but it also united a lot of people,” Bernals recalls. “We helped to stop the war. Because of that, it felt like what we did counted. Something like a million and a half people demonstrated every day when the war between the government and the guerrillas started. I was very involved. I was writing and reading about the situation, helping to send food, and demonstrating on the marches. It was great. I was young, and it was fun. And, I’ve got to say, I met my first girlfriend – my first real girlfriend – there as well. It was a great place to meet girls!”

Sex and politics. There’s nothing po-faced about Bernal’s political engagement. It’s wrapped up in movies, fun, friendships, music, travel, theatre and family. There’s something pleasing and traditionally bohemian about all this. There is often a sense in Europe and North America, that we are too comfortable, cynical even, and few people believe that protest – let alone art – can make a difference. Bernal would get along just fine in Paris circa 1968.

All of which helps to explain why he spent the past ten days at the World Trade Organisation summit in Hong Kong. His world doesn’t end with himself and his films. In Hollywood, political engagement, more often than not, means rash gestures and red faces all round. Bernal’s engagement is more steady, more regular, more constant. He quietly attended the protests at the G8 summit in Edinburgh last year on the same weekend that Madonna, Elton et al performed at the Live 8 concert in Hyde Park. In Hong Kong, he sat in meeting after meeting, discussing ideas, presenting case studies and assisting delegates such as Mary Robinson, the former Irish president (“La Presidenta!” as Bernal calls her, laughing). Before travelling to Hong Kong, he spent some time in Chiapas, discovering for himself the effect that free trade is having on local maize and coffee producers.

He’s fully aware that his profile as an actor is a selling point for organisations such as Oxfam, but still he makes sure – indeed demands – that he’s fully informed. He’s not interested in being an intelligent pretty face. He wants to get stuck in. He arrived at the Hong Kong summit with an undefined role, but was soon speaking out at meetings.

“Little by little, I started to get into it and became really interested in everything,” he explains. “Oxfam asked me if I wanted to be in the talks and negotiations.”

He jokes about something else that he picked up at the summit, after some Germans he met fell about laughing when they heard his name. “Gael” it turns out, means “horny” in German. You can already see the pin-up poster tag-line in the German equivalent of Teen Vogue: “Ich bin Gael”, it would read, pasted across a brooding portrait of the actor. It wouldn’t be anything new. “Mexican heart-throb”, “Sex Mex”, “The sexiest thing to come out of Latin America since Ricky Martin” are just some of the tacky headlines – often in upmarket publications – that have been written recently about Bernal.

The conversation turns to Live 8. Bernal admits that he feels a strong sense of unease towards events like these.

“I was a bit critical of Live 8. The people that organised it act as if they are there to safeguard our souls, and present it as a civil action, as if it’s our civil duty to go to a concert. Many of the people who took part made no more effort to do this concert than they would to make a Pepsi commercial. Some of these artists are the same people who advertise Coca Cola. People in Mexico don’t have clean water, yet they’ve drunk Coca Cola all their lives. It’s cheaper to get a Coke than to get clean drinking water. That in itself is a strong image of how much power such companies wield across the world.”

Such independent thinking is present too in Bernal’s attitude to films and filmmaking. He’s happier on the margins, where the ideas and imagination lie. It’s interesting to contrast his career with the young American actors of a similar stature – those who, one minute are hailed as the new saviours of independent cinema, and the next, are dressing up as Spiderman or nestling happily in King Kong’s computer-generated fur. It’s easier to say yes than it is to say no, as Bernal has consistently replied to all approaches from Hollywood.

The screenwriter Milo Addica (Monster’s Ball and Birth) tells a good story about how Bernal accepted the lead role in The King, which he wrote and produced. It’s an independent American movie that British director James Marsh shot in late 2004. When the film was still in the casting stage, many young American actors read the script and liked it, but, as Addica recalls, backed off for what he calls “moral reasons”. They didn’t like the film’s violence or the ambiguity of a lead character who starts out as a hero, but commits an horrific act in the film’s closing moments. Bernal, on the other hand, leapt at the chance. He plays Elvis Valderez, a young American with a Mexican mother, who leaves the navy and goes in search of his father (William Hurt), a popular Baptist preacher who never knew his illegitimate son. It’s a search that ultimately has terrible consequences. Bernal does a good job in his first American film.

“We went to a number of young actors, all of who you know but I won’t name names,” Addica explains. “They all liked the script but were concerned with the audience’s perception. They wanted changes made to accommodate that. Of course, when you pay an actor $20 million he will do an Irish jig on the table for you. He doesn’t give a flying fuck.” Needless to say, $20 million was not on offer for The King.

Bernal is not easily tempted by a pay cheque. “A film with no point of view is such a waste of money,” he considers. “So much money is spent on films. Oh man, spend that money somewhere else!”

Bernal’s attitude to cinema is rooted in Mexico – rooted in the struggle to get films made – personal stories, real storytelling, strong ideas. He says that making The Motorcycle Diaries, for which he travelled through Argentina, Peru and Mexico, reaffirmed his commitment to Latin America and Latin American cinema. Last month, his production company in Mexico City opened for business in partnership with Diego Luna. They’ve already launched a travelling documentary festival that began in Mexico City and is due to visit 16 towns across the country.

As an actor, Bernal is drawn to the filmmakers he has worked with. He wants to learn more, and says unashamedly that he usually wants to be friends with his directors.

“That was the best thing about all these films, on a very personal level, getting to know these people,” he says. “To be their friends, actually. That’s the best thing, and I really get emotional about that. Many people have explained what cinema is, but so far, to me, the best appreciation is that cinema is further proof, further affirmation that fiction can move people more than reality, more than the facts. Also that in the process of making films you get to travel and make friends.”

This isn’t just talk. Michel Gondry, who last year directed Bernal in his latest film, is effusive about the actor who he now counts as a good friend. In The Science of Sleep, Bernal plays Stephane, a half-Mexican, half-French young man whose colourful dreams have a bizarre effect on his waking-life. On the phone from New York, Gondry mentions that he has borrowed Bernal’s old apartment in the city while he works on the post-production of his film in time for Sundance. The two became close both before and during the shoot. When they first met, Gondry hadn’t quite completed his script, so he and Bernal discussed ideas together. Gondry is happy to credit Bernal with offering crucial input to the finished screenplay.

“He’s a great person on top of being a great actor,” Gondry says warmly. “He’s very caring and we’ve become very, very close. He’s very committed. The character he was playing in my film is close to me, so we had to find out what we both had in common. That takes time, and he was really pleased to spend time getting to know me. He’s also just a machine of happiness. During the shoot, he would always make everybody happy and entertain them.”

We walk around the corner and head back to the hotel, still talking about films, Mexico, London and New York, before saying goodbye in the lift. Bernal still has places to go today. The first is the local cinema, where he plans to catch the Tommy Lee Jones-directed Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada, a superb film written by his fellow countryman Guillermo Arriaga, the writer of Amores Perros and 21 Grams. The second is with a TV set in a bar somewhere. His local football team in Mexico are playing in a cup final tonight. He wouldn’t miss it for the world. The revolution rolls on.